WW II AND THE MODERN ERA:

1941 to PRESENT

At the conclusion of the final Joint Reunion Encampment the town quickly returned to a normal routine, and like the rest of the nation turned it’s attention to the escalating war mood in Europe. The political feelings in the town and county tended toward the conservative side. The “New Deal” had gained modest support during the 30s, but as war clouds gathered around the globe the majority favored an isolationist posture. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war against the U.S. resolved the political debate. Immediately a patriotic fervor burst forth in county and town and “America first” was quickly forgotten.

Once again Gettysburg’s reaction to the nation going to war mirrored the rest of the country. There was the immediate rush to enlist by the eligible males. There were moments of irrational anxiety, such as occurred after the Gettysburg Times reported that nine county manufacturing companies (none in Gettysburg) with war material contracts might be targets for axis sabotage, and Gettysburg could be subject to bombing by Axis bombers, because of the battlefield was a significant federal property. No one thought to consider that the Battle of Britain in 1940 clearly demonstrated that the German’s had no bomber capable of reaching much beyond London from their French coast airbases, much less across the Atlantic to the U.S. mainland. Like every other town and city in the nation this reality did not deter the rapid organization of a local civil defense plan. Gettysburg quickly had citizens practicing blackouts at night with volunteer wardens, wearing WWI steel helmets, roaming the streets looking for violations. During daylight hours other volunteers manned roof tops to spot, plot and report airplanes passing overhead.

What did happen to Gettysburg economically was the opposite the experience for the rest of the nation. The Great Depression ended it’s twelve year run with the war time mobilization of the nation’s manufacturing potential. Gettysburg’s leading industry, tourism, was essentially shut down for the duration of the war by the federal government’s immediate rationing of gasoline and automobile tires. The vast majority of the nation’s citizens were limited to several gallons of gas per week, drastically limiting everyone’s mobility and ability to take even the shortest of trips. Since the early 30s the transportation of choice of visitors to Gettysburg was the automobile. These folks stopped coming and Gettysburg’s economy was hit with a recession much greater than that experienced during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Unlike WWI, there was no large military training camp established on the battlefield to offset the absence of tourists. From time to time motorized troop convoys passing along the Lincoln Highway stopped over night using the Park grounds for a bivouac area and lining the Park roads with their vehicles before moving on the next day. There were a few temporary uses of the Park grounds for small unit infantry tactics training, as well as the occupation of the old 1930s Conservation Corp Camp(CCC) compound in McMillan’s Woods by an Intelligence detachment sent from nearby Fort Ritchie. The latter group setup in CCC # 2 in the summer of 1943 and renamed it Camp Sharpe. They stayed for almost a year, leaving in July 1944. Their enjoyment of the town’s amenities was welcomed, but did not add a lot to the local economy.

Just a month before Camp Sharpe was vacated an advance party of German prisoners of war were brought to Gettysburg to begin construction on a outdoor prison camp on Park land adjoining the Emmitsburg Road just opposite Ziegler’s Grove and the current site of the Cyclorama Building. During construction of the camp the prisoners were housed in the National Guard Armory on West Confederate Avenue. In July the camp was ready and the advance party was joined by 350 additional prisoners and a guard cadre of 60 U.S. army personnel. The prisoners were brought here to serve as paid laborers on the areas farms and orchards, shorthanded by enlistments and the draft. They were paid a $1 a day with 90 cents deducted by the government for the cost of their imprisonment. In November 1944 they were shifted to the barrack quarters at Camp Sharp. The last prisoners left the camp in April 1946, 11 months after Germany surrendered. Like the earlier Ft. Ritchie contingent, the guard cadre were enthusiastic patrons of the town, but added little to the overall economy.

Despite the lagging tourist economy the town responded with the same zeal to support the cause as they first did eighty years earlier when the civil war broke out. Women volunteered to the local Red Cross Chapter program by preparing thousands of surgical bandages and ancillary apparel for GIs, the exact same support given by their female ancestors in 1861-65. The citizens were extremely generous with their support of the six wartime Bond drives initiated by the federal government to help pay for the huge cost of the war. Like everywhere else in the nation Gettysburg’s school children participated by buying ten cent savings stamps in weekly classroom drives. A completed stamp book would be turned in for one $25 war bond.

The surrender of Germany to Allied forces commanded by Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower in May 1945, brought a conditioned sense of relief, but no spontaneous out break of public celebration in Gettysburg. There were too many local boys still in harms way in the Pacific Theater. This pent up anxiety, did break loose three months later when Japan called it quits in August. VJ-Day was the end of the war. In Gettysburg, in every town in the county, state and nation the celebration was loud, long and joyous. THE GETTYSBURG TIMES reported: “...Gettysburg came safely through the first wild hours of it’s celebration...fire sirens howled, factory whistles blared, auto horns vied with church bells, the fire bell, the courthouse bell...in telling the community that the end of the war had come.”

Following the joy of victory in WW II, the town quickly made the adjustment back to peace time status even though some of the governments rationing and price controls remained in effect through 1946. Service men returned to reestablish jobs and begin families. On the National scene labor disputes, generally over wages, that were put aside during the war years bubbled up to the surface. Bitter work stoppages by coal workers and railroad workers were headline news. Labor unions were not entrenched in Gettysburg and the county, but disputes did arise. During the winter of 1945-46 the workers at Gettysburg Furniture Factory where a union, the United Furniture Workers of America, represented the workers went on strike for better wages. To this extinct Gettysburg labor was following the national pattern of worker unrest. Unions were not generally popular in this part of Pennsylvania. The Gettysburg Times refused to mention the existence of the dispute in their coverage of local news. In time the strikers, isolated in their fight, went back to work without gaining any concessions from management. To the present day labor unions have not had a strong position in Gettysburg or Adams County. Manufacturing jobs are a relatively low percent of the county work base, particularly in Gettysburg, and therefore labor unions do not have a large platform for support in the general population.

Over the years following WWII Gettysburg’s modest manufacturing companies went away or went out of business. The silk mill, the sewing factories, the milk bottling plant, the Victor Rubber Products plant and finally the Gettysburg Furniture Company, all of them the core of the town’s manufacturing industry, left the scene by the mid 1960's. Town leaders fought to stem the tide. The Gettysburg Industrial Development Authority(GIDA) was created to encourage new business to locate here. In 1968 they were able to announce that Westinghouse Electric Corporation would build a substantial manufacturing facility just north of the town. It opened that fall employing several hundred local workers to operate multiple shifts. Today it is no longer Westinghouse, but the plant is still operational and the largest single manufacturing employer in Gettysburg. Promotion of the area for business development continues under the county’s Economic Development Corporation, the successor to GIDA. The EDC facilitated the arrival of the Pella Corporation, a window manufacturing company located just east of town in the county’s Industrial Development Park. Pella’s stated intention for the near future is to create a significant number of skilled labor and technician jobs to be filled by local employees. Meanwhile tourism constitutes the largest employment base in the Gettysburg area.

Promotion of the area for business development continues under the county’s Economic Development Corporation, the successor to GIDA. The EDC facilitated the arrival of the Pella Corporation, a window manufacturing company located just east of town in the county’s Industrial Development Park. Pella’s stated intention for the near future is to create a significant number of skilled labor and technician jobs to be filled by local employees. Meanwhile tourism constitutes the largest employment base in the Gettysburg area.

Promotion of the area for business development continues under the county’s Economic Development Corporation, the successor to GIDA. The EDC facilitated the arrival of the Pella Corporation, a window manufacturing company located just east of town in the county’s Industrial Development Park. Pella’s stated intention for the near future is to create a significant number of skilled labor and technician jobs to be filled by local employees. Meanwhile tourism constitutes the largest employment base in the Gettysburg area.

Promotion of the area for business development continues under the county’s Economic Development Corporation, the successor to GIDA. The EDC facilitated the arrival of the Pella Corporation, a window manufacturing company located just east of town in the county’s Industrial Development Park. Pella’s stated intention for the near future is to create a significant number of skilled labor and technician jobs to be filled by local employees. Meanwhile tourism constitutes the largest employment base in the Gettysburg area. Gettysburg had always been a town on the leading edge of adopting new technology. By the early 1860s it was using gas for illumination, had a gravity distributed water system, a railroad terminal and the latest in communications, the telegraph. By the end of WW I electric powered home illumination had replaced gas. Since 1908 neighbors and business establishments were talking with each other via the telephone. In keeping with that innovative spirit, the town jumped into the newest technology emerging from WW I, aviation. In 1929 two local entrepreneurs, David Forney and Myles Klinefelter, laid out an airstrip on the fields southeast of the old Forney farm buildings over which confederate infantry moved to strike the right flank of the Union 1st Corps on the afternoon of July 1st, 1863. The rather crude facility was improved with a hanger and a “on the fly” air mail pick up and drop system. The field hosted some shows and stunt flyers as well as local “joy ride” business, but never really got of the ground as a profitable commercial venture. Before celebrating it’s tenth anniversary the airport was closed. Aviation did not falter on the national level and WW II fostered airplane technology development which transferred readily to peace time commercial usage. Sensing a change in the business potential for commercial and private flight, Charles Doersom opened an airport just west of town on Route 30. The Doersom Airport is still in operation today for private service. Commercial service is yet to catch on in Adams County, primarily inhibited by the lack of industrial development required to support a sufficient level of demand to support the service.

Just as with the end of WW I, the end of WW II brought about a surge of tourist visitation to Gettysburg. The automobile was now the undisputed king of transportation for those coming to see the old battlefield. This brought about major changes in the services provided to support the visitors needs. First and foremost among these was the immediate proliferation of motels, many with attached or associated restaurants, springing up on the outskirts of town. Some, such as the Battlefield Motel on the Emmitsburg Road were constructed right on the ground made hallowed by horrific combat between soldiers 90 years earlier, making them doubly attractive to those wanting to experience a closer sense of history. The impact on the long established in-town hotels and restaurants was devastating. These facilities were built around the site of early highway intersections and later train terminals for convenient accessibility to travelers and visitors. Now a newer, cheaper convenience to this historic market was the motel, completely bypassing the traditional facilities in the center of town. One after the other they all closed.

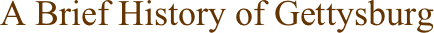

The last to go was the grandest, the Hotel Gettysburg. This stately building’s structural “roots” in the town square went back to 1797 when it was initially called Scott’s Tavern. It would undergo a number of name changes and renovations, but remained from it’s beginning till it’s end 167 years later, the community center of Gettysburg as well as a welcoming haven for over- night guests. In 1810 it became the Indian Queen. Six years later it became the Gettysburg Hotel. That same year,1816, a young Thaddeus Stevens arrived in town and set up a law office in the hotel. A few years later the Gettysburg Hotel became the Franklin House, it’s name during the Civil War. The hotel was not occupied during the battle by soldiers of either army. This may have been a snub on the Confederate’s part because owners George McClellan and his brothers were avid Republicans. Confederate officers made the nearby Globe Inn their unofficial headquarters, which was also the town’s Democratic Party headquarters. About ten years after the war the name changed from Franklin to McClellan House. In 1890 the name changed to Hotel Gettysburg which remained until the new age lodging forced its doors to finally close as a hotel in 1964.

Dignitaries from all walks of life had entered the grand old hotel’s doors during it’s long existence. The star visitor it’s last decade was President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Thus the hotel joined the David Wills house across the square with the distinction of serving sitting presidents in Gettysburg. The Wills house had been Lincoln’s unofficial headquarters for a night and day in 1863. The hotel served unofficially as Ike’s Gettysburg headquarters for most of his presidency. In late summer 1959 Eisenhower moved his “vacation office” from the farm (at Mamie’s insistence) to a second floor suite in the hotel. On the night of January 21, 1961 a large group of Gettysburg citizens welcomed ex-President and Mrs. Eisenhower “home” with a grand dinner in the hotel’s dining room. On February 11, 1983 the hotel building burned to the ground. After years of having it’s charred ruins serve as a public eyesore, it was rebuilt on the old building’s foundations, and opened as an upscale hotel option to motel accommodations for visitors.

At the time the hotels were leaving town the NPS announced plans to move out of their offices located in the U.S. Post Office building on Baltimore Street, where they had their administrative offices and visitor greeting center. In 1961 they left the center of town and moved into a new Visitor Center within the park near the “High Watermark” on Cemetery Ridge. This removed a Park presence from downtown Gettysburg which had been established by the War Department in 1895 and the GBMA before that. There was no immediate negative fallout, but time and the distance would slowly create a chasm between the town and the Park administration which in later years would become a significant barrier to communications and mutual cooperation.

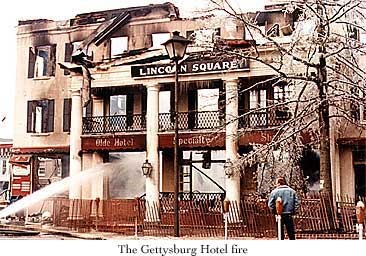

Following the emergence of suburban area motels was the growth of a new type of tourist marketing strategy. The older museum-gift shops which were so relevant to the veterans and their succeeding generations of families were pushed aside as not relating to the new visitor who had little direct identification with the lives and views of the veterans. They were replaced with interpretive creations of the battle and the civil war generally, such as wax museums, electric maps, dioramas, slide and film shows. Souvenirs were no longer artifacts from the battlefield or items related in design and theme directly to the Battle of Gettysburg. The souvenirs became, and remain today, generic to the Civil War.

Following the emergence of suburban area motels was the growth of a new type of tourist marketing strategy. The older museum-gift shops which were so relevant to the veterans and their succeeding generations of families were pushed aside as not relating to the new visitor who had little direct identification with the lives and views of the veterans. They were replaced with interpretive creations of the battle and the civil war generally, such as wax museums, electric maps, dioramas, slide and film shows. Souvenirs were no longer artifacts from the battlefield or items related in design and theme directly to the Battle of Gettysburg. The souvenirs became, and remain today, generic to the Civil War. The early sixties brought other significant changes that impacted Gettysburg’s quality of life. First was the arrival of the Eisenhowers from the White House to their farm on the southern border of the national park. Ike was immensely popular both as a two term president and as the nation’s and the world’s number one WW II hero. His presence attracted tourists who otherwise might not have made the trip. His world persona brought foreign dignitaries to visit him at his farm with an entourage of domestic and foreign press, reinforcing the world’s awareness of the little town named Gettysburg. Gettysburg now had the very unique position of possessing three one-of-a kind circumstances, any one of which assured it a prominent place in history; the Battle of Gettysburg, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and the final home of the savior of the free world.

The sixties saw a wave of U.S. highway expansion and improvement which locally had Route 15 bypass Gettysburg to the east and south and greatly reduce the driving time to Harrisburg in the north, and Frederick, Baltimore and even the Washington D.C. to the south. Gettysburg area residents could now readily commute to new and better job opportunities. A high number of workers took that option without having to relocate their homes. The commuting convenience encouraged others living in the crowded and costly big city suburbs to relocate their homes to the Gettysburg area and commute to their existing jobs. This phenomenon took a lot of the eligible work force and their earnings power out of the area. It also kicked off a wave of development which impacted schools and other infra structure services. Gettysburg did not have room to expand being surrounded by the national park on three sides and a neighboring township. There was not enough available space in town to absorb the new housing demand.

Expanded federal government social service programs coming out of President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” initiative were being established in Gettysburg, the county seat, for administration to those needing and qualifying for the new services. This naturally encouraged those eligible for the new services to seek housing in town where they could readily access the serving agencies. The combined pressures from out of state new comers and increased demand for low scale affordable housing resulted in rapid suburban housing development, much of it on a upper scale level. New sub-communities such as Lake Heritage, Twin Oaks, Twin Lakes, Woodcrest and Colt Park , all but the latter cropped up in the surrounding townships. Many long time home owners in Gettysburg moved out and rented their old residences or sold to absentee landlords who in-turn rented to meet the rising demand for affordable housing in the borough. The larger structures were converted to multi family apartments, a practice encouraged by demand and financial rewards. At present the majority of the residents of Gettysburg are rent payers, a high percentage of those living in multiple occupancy residences. This has changed the historic character of the town and placed serious strain on the Borough government and Gettysburg Area School Board to meet the accelerated demand for services within an acceptable tax level. Once again the rise of post war problems such as citizens fleeing the town or city for the presumed freedom and improved quality of life to be found in the suburbs was not unique to Gettysburg. This was and still is a national phenomenon, attributable to a combination of improved roads, affordable personal transportation and a long trend of a growing economy.

The 1960s also brought a redress to long standing racial inequalities in the form of the Civil Rights Acts of the Johnson administration. The impact nationally and in Gettysburg were profound. Since the early 1800s racial segregation had existed in all aspects of town life in Gettysburg. Segregation in the public schools had ended in 1932, but color barriers were still prominent in all other significant aspects of town life ten years after the end of WW II. There was hiring discrimination. Even in the tourist service jobs blacks were denied opportunity for jobs involving direct contact with the public. The excuse cited for discrimination was that employers feared they would lose tourist business if blacks were given customer contact jobs. As a result 36+% of the black work force worked out of town in the early 50s. The same scenario of discrimination was practiced in the public area. Blacks were not welcome to stay as guests in hotels or motels. Most of the town’s restaurants would not seat blacks, local or tourist. Even personal care shops such as barber shops and beauty salons were closed to black patronage, forcing many of them to go to Harrisburg or York for these services. The movie theaters admitted black patrons, but requested them to sit in the segregated balconies. Social segregation was less clearly defined. Often it existed by choice of the minority to avoid being subjected to a feeling of not being wanted. There were separate American Legion Posts, the Albert J. Lentz Post for white veterans and the Dorsey Stanton Post for African American vets. They had their separate parades and Post sponsored social events. In the 1930s there were two black community service clubs, the Elks and a Masonic Lodge, both forced to disband by the economic effects of the depression. White churches, excepting St. Francis Xavier catholic church, did not encourage black membership. The African American community had three churches of their own. No blacks were volunteer firemen and none ran for public offices. The Girl and Boy Scout groups were not segregated. Housing was definitely segregated with black housing pretty much restricted to the Third Ward. It was not a ghetto situation. The Third Ward had historically been a mixed neighborhood and remains that way today. Sidney O’Brien, Gettysburg’s first black property owner, lived on South Washington Street across from Breckenridge Street. Her neighbor immediately to her south was Adam Pfautz, a white man. All the same, the blacks lived there under a strict code of segregation carried out by the real estate profession. An anonymous real estate agent explained to an interviewer in 1952: “I would not think of placing them anywhere else....The white people wouldn’t stand for it.”

Despite this historic and pervasive condition of discrimination the races in Gettysburg coexisted very cordially over time. In the late 1950s and early 60s black and white activists joined together to try and remove some of the most obnoxious barriers. A biracial Committee on Human Relations was formed in town patterned after the existing State Committee. They targeted occupational discrimination, bringing forth pressure for better employment opportunities for blacks and they met with some success. Kennie’s Market was the first to respond by hiring blacks as clerks. The A&P store followed suite. The federal government stepped in with it’s sweeping anti discrimination laws later in the 1860s following uprisings across the country over this same sort of discrimination. Gettysburg achieved it’s positive results without the polarizing violence experienced in so many other areas. Today most of the old discrimination is gone by force of law if nothing else. There is certainly still some vestiges of social discrimination within the community, but it is on an individual basis. This is a personal attitude that can not be legislated away or punished unless it is expressed in violation of legally established civil rights.

Over the years a strong bond, initially emotion based and later economic based, had grown between the Gettysburg National Military Park(GNMP) and it’s neighbor, the town of Gettysburg. In the eyes of the local area citizens the relationship was more like family than close neighbors. There was, and still is, an underlying sense of ownership or possessiveness regarding the park on the part of town. Perhaps that harkens back to the fact that today’s GNMP had it’s beginning as a result of action undertaken by local Gettysburg citizens immediately following the end of the battle. Like all family relationships, emotion is never far from the surface, giving rise to ample points of contention over the years. The park administration, initially the War Department and later the National Park Service(NPS), has historically treated the relationship with Gettysburg and the local area as neighbors, with some mutual interests, but with far more compelling national interests and goals, driven by their congressional mandate to interpret the battle history and protect and preserve the natural and cultural resources.

The reality over the years has often been what is a plus for one of these two entities is not necessarily perceived as equally as good by the other. This has never been more true than over the last forty years. The arrival of the 1960s was accompanied by a number of significant events and related changes that would dramatically impact the GNMP and its neighbor, Gettysburg, giving rise to a number of bitter and contentious confrontations.

The four year Civil War Centennial celebration was the biggest national related event since the Grand Reunion at the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. In anticipation the NPS kicked off the Mission 66 national parks improvement program in 1960. Part of the plan was the modernization, or rather the creation of the Visitor Center at Gettysburg. Heretofore there had not been a real “visitor center”. The NPS staff was housed in the second floor of the U.S. Post Office on Baltimore Street with only a small information desk for public interface. In 1961 a new Visitor Center featuring the 1880s cyclorama painting of Pickett’s Charge, was built in Ziegler’s Grove along the east side of the Emmitsburg Pike not far from the scene captured in the famous painting. The lightly developed land bordering the Emmitsburg Pike from it’s intersection with S. Washington Street and Taneytown Road south to the U.S. Park Service property was quickly purchased by entrepreneurs.

The four year Civil War Centennial celebration was the biggest national related event since the Grand Reunion at the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. In anticipation the NPS kicked off the Mission 66 national parks improvement program in 1960. Part of the plan was the modernization, or rather the creation of the Visitor Center at Gettysburg. Heretofore there had not been a real “visitor center”. The NPS staff was housed in the second floor of the U.S. Post Office on Baltimore Street with only a small information desk for public interface. In 1961 a new Visitor Center featuring the 1880s cyclorama painting of Pickett’s Charge, was built in Ziegler’s Grove along the east side of the Emmitsburg Pike not far from the scene captured in the famous painting. The lightly developed land bordering the Emmitsburg Pike from it’s intersection with S. Washington Street and Taneytown Road south to the U.S. Park Service property was quickly purchased by entrepreneurs.  This section of the old Emmitsburg Road was renamed Steinwehr Avenue. New restaurants, motels, gas stations, souvenir shops and ‘interpretive presentations” quickly sprouted up, replacing the existing Victorian style, and at least one pre civil war, residential houses. The attraction for development was the close as possible proximity to the new NPS Visitor Center and spacious parking lots where the tourists were being directed to get information and to begin their tours.

This section of the old Emmitsburg Road was renamed Steinwehr Avenue. New restaurants, motels, gas stations, souvenir shops and ‘interpretive presentations” quickly sprouted up, replacing the existing Victorian style, and at least one pre civil war, residential houses. The attraction for development was the close as possible proximity to the new NPS Visitor Center and spacious parking lots where the tourists were being directed to get information and to begin their tours.The new tourist strip definitely filled a need created by the marked increase in visitation to Gettysburg generated by the public’s fascination with the Civil War created by the national centennial publicity. On the surface this looked to be a win- win situation between entrepreneurs and borough government who reaped tax benefits and the NPS whose visitors needed the new services. There were those in the old commercial center of town who saw it differently. Those who’s tourist businesses were now not patronized because of the exodus of NPS and the tourists out of the center of town to the southern suburbs. As noted above, this forced the Hotel Gettysburg to close it’s doors as a hotel-restaurant after a 167 years of continuous operation.

The renewed interest in the battlefield of Gettysburg put tremendous pressure on the NPS to improve the resource. This meant acquiring and interpreting more ground within the park’s boundary and clearing non historic buildings and businesses that interfered with the visitor’s interpretive view. Removing taxable land from county and Cumberland Township tax roles kicked off a heated and bitter debate. The divergent points of view between the NPS and local park neighbors as to priorities for park management clearly emerged over the issue of additional park land acquisition. The opposition saw the NPS’s move as detrimental to local interests. The NPS saw an obligation under their legislative mandate to improve the interpretation of the field for a national constituency. They continued with their acquisition plan. 1990 congressional action has set a final boundary line for the park, but permits acquisition until that limit is fulfilled. Bitter local opposition to this compromise still smolders within the community today.

A number of important, but less contentious issues have occurred during the past 40 years. They have been related to the frequency of mowing of the fields, the one- way designation of park roads, cutting of foliage and trees in an effort to expose the critical terrain features which influenced the outcome of the battle, the recent taking and removal of a prominent observation tower which dominated the serenity of the town’s and Soldiers National Cemeteries as well as the “High Water Mark” memorial site, a deer reduction and management plan, and the infamous “railroad cut” desecration of 1990.

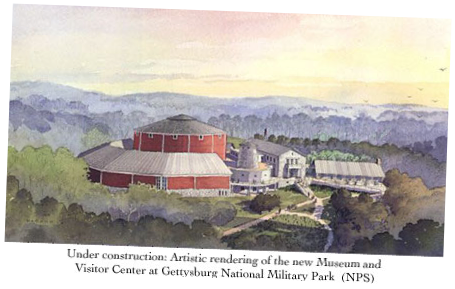

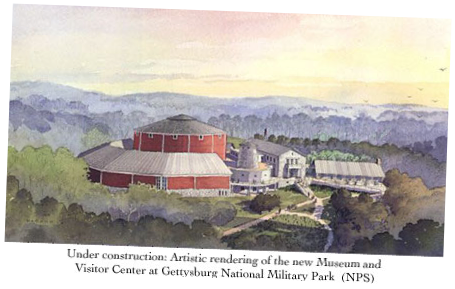

All of these issues, pale to insignificance in comparison to the long, bitter and inflammatory fight over the NPS’s decision to relocate and build a much larger, technology updated visitor center-museum. The plan included an expanded bookstore, eating facilities, retail souvenir shop and an a battle orientation film with presentation theater. The center was proposed to be erected by a private partner, selected by an open biding process, on privately owned land a quarter of a mile removed to the east from its present site and the existing Steinwehr Avenue tourist services. The existing visitor center along with its ample parking lot, which “unofficially” serves current visitors with a parking facility while they patronize the Steinwehr Avenue merchants, would be removed when the new one opens. The opposition to this NPS plan was led by the business owners along Steinwehr Avenue. Other organizations, such as the Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association and individuals, local and elsewhere, vigorously voiced their opposition to the NPS plan. They were joined by the Borough government who were also concerned by the threat of loss of business by the Steinwehr Avenue businesses, and angered by the fact that they felt they had not been briefed and solicited for input up front by the local NPS management. The three year long public debate grew in acrimony and often turned personal, particularly in attacks on the Park Superintendent. In the end, concessions were made in the Park’s General Management Plan (GMP) to reduce the commercial retail facilities in the new Visitor Center. In addition the NPS committed to enter into a formal partnership with the Borough government and civic leaders to develop and implement a town interpretive plan to be included in the park’s recommended visitor tour. The objective is to bring a large number of visitors into town, and expose them to the broad history of the town and the unique role it’s citizens played during the titanic events of 1863. The rewards are twofold: the visitor’s expanded learning experience, and the town’s opportunity for downtown commercial revitalization.

The three year long public debate grew in acrimony and often turned personal, particularly in attacks on the Park Superintendent. In the end, concessions were made in the Park’s General Management Plan (GMP) to reduce the commercial retail facilities in the new Visitor Center. In addition the NPS committed to enter into a formal partnership with the Borough government and civic leaders to develop and implement a town interpretive plan to be included in the park’s recommended visitor tour. The objective is to bring a large number of visitors into town, and expose them to the broad history of the town and the unique role it’s citizens played during the titanic events of 1863. The rewards are twofold: the visitor’s expanded learning experience, and the town’s opportunity for downtown commercial revitalization.

The three year long public debate grew in acrimony and often turned personal, particularly in attacks on the Park Superintendent. In the end, concessions were made in the Park’s General Management Plan (GMP) to reduce the commercial retail facilities in the new Visitor Center. In addition the NPS committed to enter into a formal partnership with the Borough government and civic leaders to develop and implement a town interpretive plan to be included in the park’s recommended visitor tour. The objective is to bring a large number of visitors into town, and expose them to the broad history of the town and the unique role it’s citizens played during the titanic events of 1863. The rewards are twofold: the visitor’s expanded learning experience, and the town’s opportunity for downtown commercial revitalization.

The three year long public debate grew in acrimony and often turned personal, particularly in attacks on the Park Superintendent. In the end, concessions were made in the Park’s General Management Plan (GMP) to reduce the commercial retail facilities in the new Visitor Center. In addition the NPS committed to enter into a formal partnership with the Borough government and civic leaders to develop and implement a town interpretive plan to be included in the park’s recommended visitor tour. The objective is to bring a large number of visitors into town, and expose them to the broad history of the town and the unique role it’s citizens played during the titanic events of 1863. The rewards are twofold: the visitor’s expanded learning experience, and the town’s opportunity for downtown commercial revitalization. It has been agreed by many that much was learned by both parties in this most recent debate/battle. The outcome has created a new level of communication and cooperation between the town and the park that had been lost almost entirely since the early 1960s. There has been a renewed recognition by both parties of a unique and enduring relationship founded in an historic bond dating back to 1863.

The Borough-NPS interpretive planning partnership is a successful work-in- progress. The plan to implement the Park’s new Visitor Center is proceeding. The combined efforts bode a bright future for Gettysburg to match it’s storied past.

WW II AND THE MODERN ERA