FEDERAL PERIOD:

1786 to 1835

Fourteen years after James Getty laid out the plan for Gettysburg, Adams County was created out of the western most lands of colonial York County.

The Scotch-Irish settlers of the Marsh Creek area had little in common with the Germans who inhabited the central and eastern areas of York County. There were strong cultural differences including religion, ideas, tastes, language and political activism. The latter element was exacerbated by the extreme distance between the "westerners" of the county and the county seat in York. They were forced to undertake a two to three days trip one way to travel the forty miles to York.

Underlying all the reasons for separation was the inherent desire for local or self determination among the Scotch-Irish. Even so, not all western York County inhabitants favored a separation from the status quo. A growing German settlement along the eastern edge of the future Adams county opposed separation. This opposition segment was not very demonstrative, allowing an active minority of the total inhabitants to place a petition for separation before the state General Assembly in March of 1789.

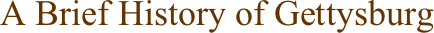

It would not be enacted for another ten years. One of the delaying factors was the determination of the location for the proposed county seat. Three towns, New Oxford, Hunterstown and Gettysburg, competed for the coveted designation. James Getty recognized the positive impact it would have on the value of real estate in his town. He offered the state appointed "Selection Committee" the annual receipts from ground rents on his lots and free land for the purpose of "building a Gaol." A group of nine residents sweetened the pot by adding $7000 to build a court house and county administration building. The package carried the day. In January 1800 Governor Thomas McKean signed the bill creating Adams County with the courts placed in "the town of Gettysburg."

It would not be enacted for another ten years. One of the delaying factors was the determination of the location for the proposed county seat. Three towns, New Oxford, Hunterstown and Gettysburg, competed for the coveted designation. James Getty recognized the positive impact it would have on the value of real estate in his town. He offered the state appointed "Selection Committee" the annual receipts from ground rents on his lots and free land for the purpose of "building a Gaol." A group of nine residents sweetened the pot by adding $7000 to build a court house and county administration building. The package carried the day. In January 1800 Governor Thomas McKean signed the bill creating Adams County with the courts placed in "the town of Gettysburg."  The designation of the name "Gettysburg" was the probably the first official use of this name for James Getty's town.

The designation of the name "Gettysburg" was the probably the first official use of this name for James Getty's town. The new county was named Adams after the incumbent United States president, John Adams. There was probably no deep statement of political philosophy in the selection of the name. The white hot partisanship between Federalist-Republicans and Jeffersonian-Democrats, so prevalent in the nation and in the county sixty years later, had yet to emerge in 1800.

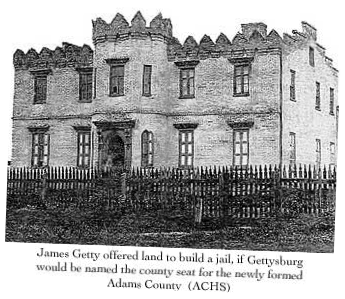

In 1804 the two story brick court house was erected in the middle of the center square. A two story brick county office building followed on the north east corner of the intersection of the square and York Street.

In 1804 the two story brick court house was erected in the middle of the center square. A two story brick county office building followed on the north east corner of the intersection of the square and York Street. Two years later in 1806 Gettysburg was granted the status of Borough giving the populace the right of local control over town matters. The stage was now set for a thirty year period of dynamic growth and development in population, buildings, local industry, education facilities and town infrastructure.

The existence of the court house attracted an infusion of lawyers into the town's professional and social make up. The growing population attracted merchants and "cottage industry" craftsmen as well as doctors, innkeepers and builders. Twenty years after Michael Hoke built his house in 1790, Gettysburg had 107 new ones made necessary by the steady growth in population.

Cottage or home based industry began to flourish. Beginning with furniture and black smithing it expanded to carriage building by the 1830's. Hotels and Inns sprouted up along the east-west and north-south trade road routes. Walkways or pavements of brick were installed along the main streets for at least two blocks from the center square.

Perhaps the most dramatic and modern improvement for the times was the provision of "city water" to the doorstep of subscribers. A group of town entrepreneurs formed the Gettysburg Water Co. in 1823. They placed a small reservoir on the hill at the intersection of S. Stratton and E. High Streets which was filled daily by wagons bringing water drawn from springs along S. Baltimore Street. The water was distributed by gravity flow via pipes constructed from augured out logs buried underneath the streets. This gravity fed system remained in operation into the 20th century. In 1823 Gettysburg was at the leading edge in the use of this water distribution technology, rivaling the major cities of the day.

The intellectual energy of the community was stimulated by the existence of three weekly newspapers. In the early years they were not as politically partisan as they would become by the mid century. They focused on state and national news, elevating the community's awareness of broader issues and events than just those encountered daily in Gettysburg. The papers effectively mitigated the barriers of distance on communications between the local community and the rest of the nation.

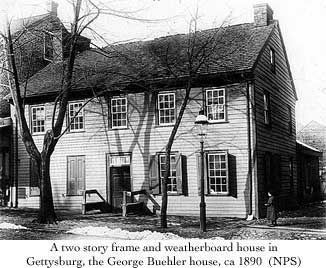

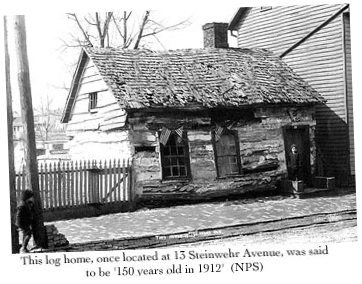

James Getty's lots were quickly bought up and dwellings erected. The growth spread out from the center square. The size and styles of architecture reflected the economic diversity of the growing population. A few, substantial, three story brick dwellings such as those erected on the square by Alexander Cobean and John McConaughy represented the houses of the town's most affluent. Cobean was the founder and president of the Bank of Gettysburg. Slightly smaller two story houses, usually of brick, were erected by the middle class professional persons and more successful merchants. Two story frame and weatherboard and occasional log dwellings were put up by the blue collar craftsmen. The many one story cottages were the homes of the semiskilled laborers, both Afro-American and Caucasian. By the end of the first four decades of the 19th century Gettysburg had 300 dwellings in this mix. (31% of the town's approximate 450 primary structures in 1863 exist today with various degrees of modification.)

With the growth came changes in the population demographics. German Lutherans began to arrive to complement the heretofore dominate Scotch-Irish make-up of the local population. A trickle of free African Americans set up homes after migrating here mainly from Philadelphia and Maryland. In 1807 the tax roles noted that Gettysburg had five slaves, all adult women undoubtedly serving their owners as domestics.

Still other people with different beliefs, both religious and political, and ethnic background were drawn to the community by the growing opportunity to ply their trades. They were Methodists and German Reformed and Roman Catholics. By the 1830's the founding Scotch-Irish found themselves to be in the minority in Gettysburg. The Lutherans were the dominant religion.

As the population grew a distinct social and economic class structure emerged. The affluent, leading merchants and professional people, occupied the top tier. The lesser merchant-craftsmen formed the broad middle class. The uneducated, semi skilled laborers were at the bottom of the pyramid. With very few exceptions the town's growing African American population was relegated to this lower tier.

Social and economic segregation was not proactively ordained. There were no "black codes" such as existed in some northern states barring African Americans from patronizing restaurants, stores or public buildings. The large majority of Gettysburg's white citizens looked upon their African American neighbors like most whites in the county, the state and the other "free states" of the north. They believed that people of African descent were inherently inferior to people of European descent and as such not entitled to equal treatment on all levels. They did accept the African American’s right to coexist, work and to own property. Socially the whites were polite, if not condescending, in their interactions with their fellow black citizens. Many of the more affluent offered live-in employment as a domestic.

The churches were non-segregated, but did not overtly address the spiritual needs of the town's African American population. The exception was the Methodist congregation who erected a church in the first block of E. Middle Street in 1822 (now the former G.A.R. hall). Their congregation included forty five African Americans. This social/religious partnership lasted until 1838. At that time the church obtained another building on the west side of town as a house of worship for the black members of the congregation. The Trustees found that arrangement too expensive and the experiment failed two years later. They temporarily returned to the Middle Street church. In 1841 “The Black Class," as they were called by the congregation, left the Methodist Church to go out on their own. In 1843 they erected a church building on Long Lane under the title of the Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal Church. While this independent move may have provided a more comfortable environment in which to pursue their spiritual needs it created a de- facto segregation of churches in the Gettysburg community.

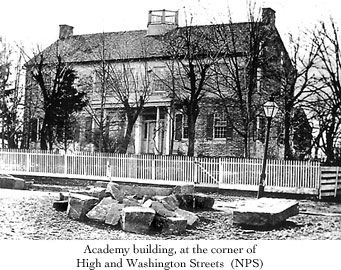

On the economic front there was little hope for the semiskilled people, black and white, of climbing above the bottom rung of the ladder. The lack of access to education was the main obstacle. In 1813 a "public school", named the "Academy Building", was built with the aid of a state grant at the S.E. intersection of South Washington and West High Streets to provide elementary and secondary education in the growing community. It was public only in the sense that it was nonsectarian and it was available to any male student whose family could afford the tuition. For the poorest families, white and black, this "public education" was unobtainable. In 1815 girls were included on a segregated or separate classroom basis. Several other "academies" or tuition based schools were founded to broaden the opportunity for access to education in the town, excepting the poorest.

In 1834 the state General Assembly passed the Public School Act which provided for local tax supported elementary education for all children where approved by local voters. Gettysburg voters approved the measure that same year. Classes were held for the most part in the houses of teachers. The town was arbitrarily divided into four districts with one in the south west section reserved for African American children. Thus classes were effectively segregated by race. The town's African American children now had access to elementary level education allegedly equal to that of the white children. The practice of racially segregated elementary schooling prevailed well into the first half of the 20th Century.

Segregation touched elements of the town life beyond schools, job opportunity and everyday life. The church graveyards were not available to Blacks for interment. In 1828 a "colored Cemetery" was established on a lot at 4th and York Streets. This plot was in use until 1905 when the remains were disinterred and moved to the newer and larger black "Lincoln Cemetery" on Long Lane.

Higher education in the form of the Lutheran Theological Seminary (1826) and the Pennsylvania College (1832) came to Gettysburg several years before the creation of free public elementary schools. The establishment of these two institutions of higher learning would have a profound and lasting impact on the town's development and quality of life that extends to this day.

Both institutions obviously served the purpose of offering opportunity for local access to higher education. Beyond this they helped to increase Gettysburg's awareness of the differences and similarities of people, places and issues in distant places of the new nation. Equally as important, it created an awareness of Gettysburg in these same far reaching places.

The Lutheran Theological Seminary was the first to arrive in 1826. Gettysburg had been chosen by the General Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church over competing sites in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and Hagerstown, Maryland. Gettysburg won the competition in part because of a repeat of the successful tactic used twenty years earlier to win the county seat designation. A group of prominent citizens pooled their resources and pledged land on Oak Ridge (now Seminary Ridge) at the western boundary of the town. The presence of a number of good roads making the otherwise remote site of Gettysburg accessible was another determining factor.

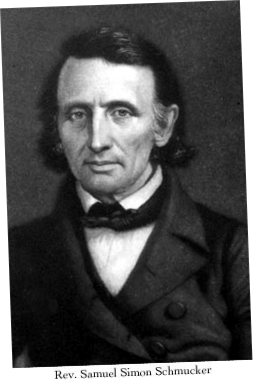

The Lutheran Theological Seminary was the first to arrive in 1826. Gettysburg had been chosen by the General Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church over competing sites in Carlisle, Pennsylvania and Hagerstown, Maryland. Gettysburg won the competition in part because of a repeat of the successful tactic used twenty years earlier to win the county seat designation. A group of prominent citizens pooled their resources and pledged land on Oak Ridge (now Seminary Ridge) at the western boundary of the town. The presence of a number of good roads making the otherwise remote site of Gettysburg accessible was another determining factor. The purpose of the new institution was to develop a cadre of educated American Lutheran ministers for placement throughout the United States. The initial class of seven utilized the "Academy Building" built to house the town's first "public school" or academy. Meanwhile the permanent campus of a classroom-dorm building and two professors houses were constructed at the permanent site "on the glorious hill." The expanding student body moved into the new quarters in 1832. The three story brick student building and flanking professor's houses still exist today. The former currently houses the Adams County Historical Society.

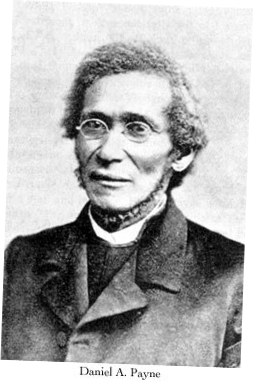

New faces from far away places in the form of aspiring ministers became temporary members of the Gettysburg community. They were not only diverse in background, but in race. The Seminary was not segregated. The first African- American student, Daniel A. Payne , arrived in 1835. Upon leaving the Seminary two years later he would go on to become a Bishop in the A.M.E. Church and the President of Wilberforce University. While a student at the Seminary, Payne left an indelible mark on the community. Recognizing the sad state of education for black children he opened and taught a sunday class for those children.

New faces from far away places in the form of aspiring ministers became temporary members of the Gettysburg community. They were not only diverse in background, but in race. The Seminary was not segregated. The first African- American student, Daniel A. Payne , arrived in 1835. Upon leaving the Seminary two years later he would go on to become a Bishop in the A.M.E. Church and the President of Wilberforce University. While a student at the Seminary, Payne left an indelible mark on the community. Recognizing the sad state of education for black children he opened and taught a sunday class for those children. Initially the greatest asset gained by the community from the arrival of the Lutheran Seminary came in the form of Rev. Samuel Simon Schmucker, the first president of the institution. Schmucker was the driving force behind the founding of the Seminary and almost single handedly kept it from faltering in the early years of its rich and storied existence in Gettysburg. He was an unyielding advocate of education. Besides establishing the Seminary he was the driving spirit behind the establishment of Pennsylvania(now Gettysburg) College.

Schmucker saw the need among his seminary students for a broader, liberal arts background to augment their theological studies. He perceived a great advantage to the Seminary and the Gettysburg community from having such a institution of higher learning. He sold the idea to the community and got the necessary signatures to petition the General Assembly. He personally went to Harrisburg to lobby for the granting of a charter to establish a college at Gettysburg. He was successful and the charter was issued in 1832. Classes began that fall in the old “Academy Building" recently vacated by the Seminary.

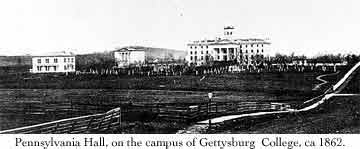

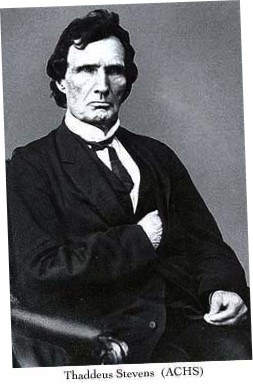

The next hurdle was obtaining funds to construct the campus. Thaddeus Stevens, a fellow townsman and strong advocate of education at every level was then representing Adams County in the General Assembly. He argued tirelessly and successfully to push a grant of $18,000 through the Assembly. After Stevens made the land available, work on Pennsylvania Hall began. In November 1837 the "Academy Building" was vacated and classes began in the new Greek Revival structure (Pennsylvania Hall) which still serves Gettysburg College today.

The establishment of these two institutions brought Gettysburg numerous benefits which clearly helped lift it above the status and profile of the other towns in the county. The professional element of the town's population was significantly broadened by the influx of the teaching professors.

Stevens and Schmucker found themselves in partnership on another front in the 1830s. Both had a strong conviction about the evil of slavery. Abolitionism was not a popular concept among the majority of town and county populations. Being principled men both entered the debate and followed a moderate path supporting the concept of African colonization to avoid being labeled and rejected as an extremist. Schmucker found other outlets to make his statement against slavery. It is largely believed that he participated to some degree in the "Underground Railway", sheltering runaway slaves on their trek north in the basement of his seminary campus home.

Stevens and Schmucker found themselves in partnership on another front in the 1830s. Both had a strong conviction about the evil of slavery. Abolitionism was not a popular concept among the majority of town and county populations. Being principled men both entered the debate and followed a moderate path supporting the concept of African colonization to avoid being labeled and rejected as an extremist. Schmucker found other outlets to make his statement against slavery. It is largely believed that he participated to some degree in the "Underground Railway", sheltering runaway slaves on their trek north in the basement of his seminary campus home. Thaddeus Stevens, after leaving Gettysburg in 1842, would go on to become a long standing member of the U.S. Congress where he was an uncompromising champion of freed slaves rights as established by the 14th and 15th amendments to the United States Constitution.

FEDERAL PERIOD