EARLY POST WAR:

1865 to 1880

With the war's end Gettysburg resumed its comparative sameness with all other northern towns and cities. Its veterans returned and immediately began the adjustment to peace time civilian life. The experience of four years of the war itself and the particular events of 1863 assured that the Gettysburg to which these veterans returned was not exactly like the Gettysburg they left, but the changes were not all that dramatic. The economic and social status were essentially the same. In many northern towns the accelerated shift from agricultural to industrial production to support the war demand remained. Gettysburg had not made such a shift during the war and remained primarily a agriculture driven economy.

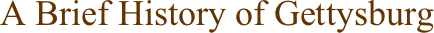

Carriage and wagon manufacturing which was so strong in prewar days did not recover. The predominately southern market suspended by the hostilities did not return with the end of the war. It would be years before the conquered southern states would recover sufficiently to be an active trading partner. Meanwhile the number of carriage makers dwindled in Gettysburg. A few, such as Culp, Danner and Ziegler and Troxell, remained in business to serve primarily local and area demand. Jacob Troxell's son Harry E. continued the business of building wagons until finally succumbing to the competition of the combustible engine in 1918.

The craft oriented, cottage-industry style of manufacturing continued. Some new lines of manufacturing such as cigar making did blossom. No new stand-alone factories went up as was common in many other northern towns. This would not occur in Gettysburg until twenty five years later. Veterans who had left a trade to go to war had little new employment opportunity to come home to. This was particularly true of African American veterans. They left as semi skilled laborers and returned from the army with few new skills. Sam Stanton was typical of the black veteran experience upon returning home. He found a job awaiting him at the Eagle Hotel stables, the same job he left to go to war in 1864. Lloyd A. Watts's experience was one of the rare exceptions. He returned, worked to qualify himself as a teacher and landed a job in the still segregated "colored school." Watts earned the distinction of being Gettysburg's first black teacher.

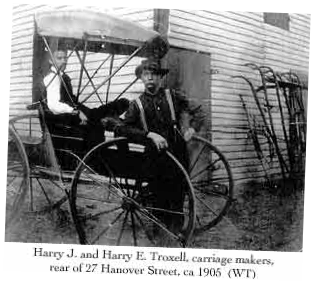

The end to hostilities did release a backlog of demand for new construction. A virtual freeze on new housing had been in effect since the beginning of 1862. The demand was for housing at the extremes of the economic spectrum. The wealthiest started a dramatic display of huge victorian style mansions along Carlisle Street north of Stevens Run or modern day Water Street. Alexander and Charles Buehler both built in the area. Robert McCurdy, president of the Gettysburg Railroad, and Professor Henry L. Baugher, recently the president of Pennsylvania College, did the same. The College expanded it's campus east of N. Washington Street to Carlisle Street and erected the Thaddeus Stevens Hall to accommodate it's Preparatory Department, an equivalent to a private high school for potential college candidates.

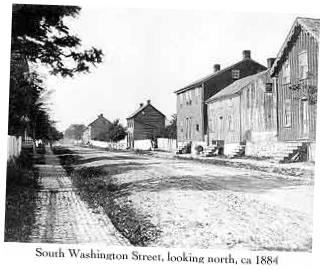

At the other end of economic spectrum much more modest, blue collar size houses were erected, primarily along Breckenridge Street at the south end of town, the east side of S. Washington Street between High and Breckenridge Streets, and the third block of W. Middle Street.

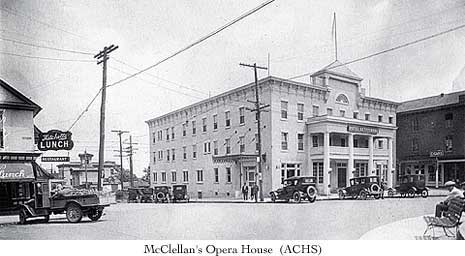

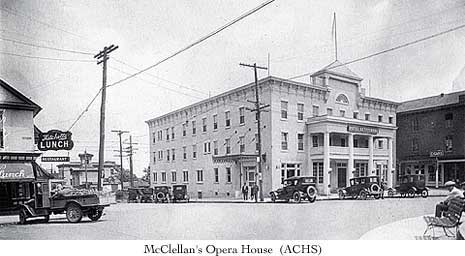

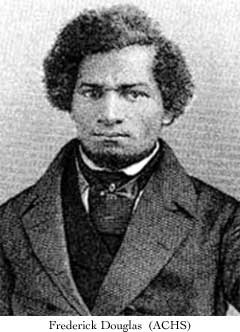

The biggest nonresidential structure erected in 1867-68 was the Agriculture Hall adjacent to the newly finished fairgrounds on the south side of W. High Street. The Agriculture Hall, built with an imposing steeple, became the cultural center of Gettysburg in the latter half of the 19th Century, although it had to share that role during the 1880's with Col. John McClellan's new Opera House on the NE Quad of the square.  The Agriculture Hall hosted lectures and stage productions, thereby providing adult education and entertainment, although often igniting familiar political fireworks between the editors of the Compiler and Sentinel. When the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglas spoke to a full house on January 26, 1869 editor Stahle charged in his Compiler that Douglas was brought here by the republicans to promote the doctrine of racial equality. The Sentinel merely complemented the orator on the delivery and content of his message, noting that the crowd responded quite warmly. Nine years later the Hall hosted a presentation of the play, Uncle Tom's Cabin stimulating, once again, a political comment by the rival papers.

The Agriculture Hall hosted lectures and stage productions, thereby providing adult education and entertainment, although often igniting familiar political fireworks between the editors of the Compiler and Sentinel. When the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglas spoke to a full house on January 26, 1869 editor Stahle charged in his Compiler that Douglas was brought here by the republicans to promote the doctrine of racial equality. The Sentinel merely complemented the orator on the delivery and content of his message, noting that the crowd responded quite warmly. Nine years later the Hall hosted a presentation of the play, Uncle Tom's Cabin stimulating, once again, a political comment by the rival papers.

The Agriculture Hall hosted lectures and stage productions, thereby providing adult education and entertainment, although often igniting familiar political fireworks between the editors of the Compiler and Sentinel. When the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglas spoke to a full house on January 26, 1869 editor Stahle charged in his Compiler that Douglas was brought here by the republicans to promote the doctrine of racial equality. The Sentinel merely complemented the orator on the delivery and content of his message, noting that the crowd responded quite warmly. Nine years later the Hall hosted a presentation of the play, Uncle Tom's Cabin stimulating, once again, a political comment by the rival papers.

The Agriculture Hall hosted lectures and stage productions, thereby providing adult education and entertainment, although often igniting familiar political fireworks between the editors of the Compiler and Sentinel. When the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglas spoke to a full house on January 26, 1869 editor Stahle charged in his Compiler that Douglas was brought here by the republicans to promote the doctrine of racial equality. The Sentinel merely complemented the orator on the delivery and content of his message, noting that the crowd responded quite warmly. Nine years later the Hall hosted a presentation of the play, Uncle Tom's Cabin stimulating, once again, a political comment by the rival papers.

On the national scene the American Industrial Revolution, which had begun in the 1820s with the introduction of the factory system replacing the individual apprentice-artisan manufacturing process, continued unabated from it's wartime plateau. The country's population came out of the war with a sense of restlessness and adventure for new opportunity. Eastern culture and homesteaders pushed rapidly westward beyond the Mississippi River. Adams County and Gettysburg would be touched by this mood. Harvey Sweney and Georgia Wade McClellan (Jennie Wade's sister) and her husband Louis were members of long time town families who left shortly after the war ended for the west. Others followed.

The town's total population actually grew by almost seven hundred between 1860 and 1870 (it would decrease by 250 in 1880). The 1870 growth included a net increase of 53 members(28%) of the African American segment. However, only 31% of this group lived here in 1860. The overwhelming majority of these new members to the Black community were listed in the 1870 US census as coming from Maryland and Virginia. It can be reasonably surmised that many of these were ex-slaves, freed by the conclusion of the war and the 13th amendment to the Constitution, and seeking opportunity in an area removed from their former enslavement. The arrival of new members directly from a slavery environment introduced an increased level of illiteracy among the Black community, up from 24.3% in 1860 to 28.1% in 1870. The immediate effect was to heighten the barrier to obtaining the better jobs requiring the ability to read and write. The immediate post war years found the majority of Gettysburg's African American community still mired in the semiskilled economic status.

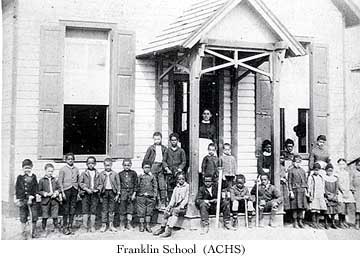

The early post war years brought little change to the educational opportunities available to Gettysburg's children. Public school classes were still limited to grades one through six. They were still racially segregated. A new "colored" school building was raised at the NW corner of Franklin and High Streets in 1870. It was known as the "Franklin School.” Lloyd Watts was appointed the first African American teacher in 1867 and was later assigned to the new "Franklin School” when it opened. Private schools or academies offering secondary classes were still available in town for those who could afford the tuition. The Pennsylvania College Preparatory Department offered racial segregated secondary courses for white males who wanted to go on to the college or university level.

Aaron Sheely, County Superintendent of Public Schools, opened a private teacher training academy in his house at the SE corner of W. Middle and S. Washington Streets. He was motivated by concerns about the general lack of subject knowledge and teaching skills prevalent among the county's teacher cadre. The curriculum was oriented to providing the teacher-student graduate an education level slightly above the secondary level. A college educated public school teacher in Gettysburg would come much later. Founded in 1867 the Sheely Normal School would graduate town and county teachers for the remainder of the century.

The quality of life was not significantly altered in Gettysburg by the ending of the Civil War. Hard work was still the order of the times, generally six days a week for all levels of the work force. There were a number of attractions and activities to provide a break in the monotony of life's routine. Several of these were post war products. Social activities still centered around the church in the form of outings and picnics.  The Agriculture Hall and McClellan's Opera House provided a steady stream of entertainers, plays, lectures and debates throughout the 1870s and 80s.

The Agriculture Hall and McClellan's Opera House provided a steady stream of entertainers, plays, lectures and debates throughout the 1870s and 80s.

The Agriculture Hall and McClellan's Opera House provided a steady stream of entertainers, plays, lectures and debates throughout the 1870s and 80s.

The Agriculture Hall and McClellan's Opera House provided a steady stream of entertainers, plays, lectures and debates throughout the 1870s and 80s. Beginning with the completion of the fairgrounds bordering Long Lane in 1867,an annual "Agriculture Fair" was staged by local entrepreneurs. The grounds featured a half mile oval horse racing track which was extremely popular with town and county enthusiasts. The formal stakes for the race competitions were bragging rights. Wagers were an "informal" side agreement, not officially condoned. Unfortunately the investment needed more than just a seasonal attraction and the grounds and annual "Agriculture Fair" were closed in 1881. Today the old fair grounds are incorporated into Gettysburg's Recreation Park.

The popular sport of horse racing remained. A five block straight track from the end of Chambersburg Street, through the square, and on to the end of York Street was often cordoned off to traffic to settle gentlemanly challenges. When the street was not available a parallel alley a half block to the north was used, and today aptly named Race Horse Alley.

Another attraction came along at the same time as the closing of the fairgrounds which caught the public's fancy and patronage. On the south side of West Middle Street, just beyond the intersection with S. Washington Street, a roller rink was erected. It became wildly popular for the remainder of the 1880s. The structure was easily convertible to a dance hall or reception pavilion and often served those purpose. By 1890 this attraction had also outlived it's life and closed, to be replaced with houses.

An elaborate vacationing venture was constructed just to the west of Gettysburg in 1869. Just beyond Willoughby Run amidst the fields involved in the July 1st fighting was a natural mineral spring. A group of out-of-town investors purchased the land surrounding the mineral springs east to the in-town intersection of the Chambersburg Pike and the old Millerstown-Fairfield Road at the foot of Chambersburg Street. What it did not include were the Seminary grounds and a few holdout residential properties. They built an imposing three story hotel equipped with the finest then available in guest amenities. The advertised nationally and quickly sold out their guest rooms. Their customers access to the resort began at the Carlisle Street railroad station in Gettysburg. From there the developers built a horse drawn train track up the street to and across the square, down Chambersburg Street to a new right-of-way (now Springs Ave.) through their property to the top of Seminary Ridge just west of Rev. Schmucker's old mansion. From there the track cut northwest across the battlefields to the hotel a mile beyond. The crowds of weekly and longer vacationers were a boon to Gettysburg's merchants. After several changes of owner/operators the venture folded in 1891. The developer's land between Springs Ave. and the Chambersburg Pike west to the Seminary property was eventually purchased by J. Emory Bair and developed in the 1890s.

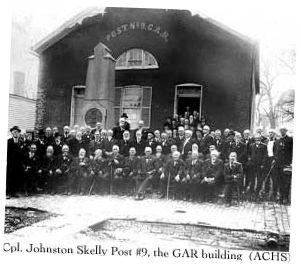

When the northern war veterans returned home in the summer and fall of 1865 they quickly turned their attention to the task of getting on with their lives. There was little time or energy spent on reflecting about their war experiences. Instead there were the tasks of family and career building. The national public's fascination with battlefields, even Gettysburg, faded dramatically. The visits to the field from distant towns and cities reduced to a mere trickle. After about ten years the veterans had settled into their new lives and began to reflect on the great adventure of their youth. The movement to organize local posts of veterans under the national association of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) gained momentum. In Gettysburg thirty one veterans in 1867 formed the Cpl. Johnston Skelly Post #9. In 1880 the Post purchased the old Methodist church building on East Middle Street as their meeting hall. This formal bonding of veterans here and elsewhere facilitated their renewed interest in their war experience and generated interest among family members. Soon individual GAR Posts and regimental associations began to make treks with their families to Gettysburg. This marked the real beginning of our nation’s compelling and lasting spiritual need to visit and revisit the battlefield at Gettysburg. It was the birth of the tourist industry that has annually been so prominent in the economy of the town ever since.

After about ten years the veterans had settled into their new lives and began to reflect on the great adventure of their youth. The movement to organize local posts of veterans under the national association of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) gained momentum. In Gettysburg thirty one veterans in 1867 formed the Cpl. Johnston Skelly Post #9. In 1880 the Post purchased the old Methodist church building on East Middle Street as their meeting hall. This formal bonding of veterans here and elsewhere facilitated their renewed interest in their war experience and generated interest among family members. Soon individual GAR Posts and regimental associations began to make treks with their families to Gettysburg. This marked the real beginning of our nation’s compelling and lasting spiritual need to visit and revisit the battlefield at Gettysburg. It was the birth of the tourist industry that has annually been so prominent in the economy of the town ever since.

After about ten years the veterans had settled into their new lives and began to reflect on the great adventure of their youth. The movement to organize local posts of veterans under the national association of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) gained momentum. In Gettysburg thirty one veterans in 1867 formed the Cpl. Johnston Skelly Post #9. In 1880 the Post purchased the old Methodist church building on East Middle Street as their meeting hall. This formal bonding of veterans here and elsewhere facilitated their renewed interest in their war experience and generated interest among family members. Soon individual GAR Posts and regimental associations began to make treks with their families to Gettysburg. This marked the real beginning of our nation’s compelling and lasting spiritual need to visit and revisit the battlefield at Gettysburg. It was the birth of the tourist industry that has annually been so prominent in the economy of the town ever since.

After about ten years the veterans had settled into their new lives and began to reflect on the great adventure of their youth. The movement to organize local posts of veterans under the national association of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) gained momentum. In Gettysburg thirty one veterans in 1867 formed the Cpl. Johnston Skelly Post #9. In 1880 the Post purchased the old Methodist church building on East Middle Street as their meeting hall. This formal bonding of veterans here and elsewhere facilitated their renewed interest in their war experience and generated interest among family members. Soon individual GAR Posts and regimental associations began to make treks with their families to Gettysburg. This marked the real beginning of our nation’s compelling and lasting spiritual need to visit and revisit the battlefield at Gettysburg. It was the birth of the tourist industry that has annually been so prominent in the economy of the town ever since. This reawakening of interest by the veterans proved to be the savior of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) and the battlefield under it's care. The rather parochial membership was running out of funds and energy. Their board included a major student of the battle, John B. Bachelder, who served as the chief historian. He had been instrumental in getting prominent generals and lessor officers from both sides to return and point out the exact places and particulars of the critical fighting. Beyond gathering data the GBMA was very limited in funds to expand and develop the field.

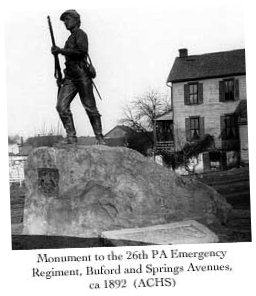

John Vanderslice of Philadelphia, an enthusiastic member of the GAR, saw an opportunity. He was responsible for organizing a weeks encampment of the GAR on East Cemetery Hill in July 1878. It became his goal to sell the veterans on taking control of the GBMA through membership subscription and memorializing their deeds in this battle and in the war with monuments placed on the field. At the same time the veteran's membership subscription in the GBMA would provide the funds to acquire more of the critical terrain. Vanderslice proposal was overwhelmingly accepted and successfully implemented during the 1880s and 90s.

John Vanderslice of Philadelphia, an enthusiastic member of the GAR, saw an opportunity. He was responsible for organizing a weeks encampment of the GAR on East Cemetery Hill in July 1878. It became his goal to sell the veterans on taking control of the GBMA through membership subscription and memorializing their deeds in this battle and in the war with monuments placed on the field. At the same time the veteran's membership subscription in the GBMA would provide the funds to acquire more of the critical terrain. Vanderslice proposal was overwhelmingly accepted and successfully implemented during the 1880s and 90s. The interest in placing memorials increased repeat visits by the enthusiastic veterans groups and their families. Tourist visitation began in earnest by 1880 and would accelerate until the coming of another war in 1917. The immediate influx of visitor dollars was welcomed. Gettysburg had been suffering along with the rest of the nation from the economic depression throughout much of the 1870s. This fresh source of outside money entering the local economy was a boon to the spirit of the business community and to it's citizens needing jobs.

EARLY POST WAR