BETWEEN THE WARS:

1918 to 1941

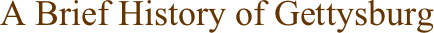

While the presence of the army training camp served as an economic boon to Gettysburg it was not without some cost to it’s infrastructure. The cobble stone and dirt streets were badly worn by the constant passage of military vehicles to and from the downtown supply warehouse in the old power house at Rail Road and North Washington Streets. Besides mud and potholes from wet weather the heavy dust generated during dry weather was choking. The frequent spreading of oil to curb the dust proved an insufficient solution. Peace time and the removal of the camp did not solve the problem. More and more automobiles were being driven through town streets by locals and tourists, who returned in greater numbers than before the war suspended battlefield visitation. In 1919 Borough Council finally provided the funds to begin paving the streets. Baltimore and Carlisle Streets were the first and the others followed. The Borough’s action was gratuitous. Gettysburg very soon would be significantly impacted by a national highway initiative.

While the presence of the army training camp served as an economic boon to Gettysburg it was not without some cost to it’s infrastructure. The cobble stone and dirt streets were badly worn by the constant passage of military vehicles to and from the downtown supply warehouse in the old power house at Rail Road and North Washington Streets. Besides mud and potholes from wet weather the heavy dust generated during dry weather was choking. The frequent spreading of oil to curb the dust proved an insufficient solution. Peace time and the removal of the camp did not solve the problem. More and more automobiles were being driven through town streets by locals and tourists, who returned in greater numbers than before the war suspended battlefield visitation. In 1919 Borough Council finally provided the funds to begin paving the streets. Baltimore and Carlisle Streets were the first and the others followed. The Borough’s action was gratuitous. Gettysburg very soon would be significantly impacted by a national highway initiative.

Since the late 19th century the leaders of Gettysburg and elsewhere were lobbying for a national memorial for Abraham Lincoln. The monument touted was a Lincoln Memorial Highway connecting Washington, D.C. and Gettysburg. Congress favored the idea of a Lincoln memorial, but did not endorse a Washington to Gettysburg highway as the fitting tribute. They proposed a Lincoln Memorial Temple, today’s Lincoln Memorial, along the Potomac River bank in Washington.

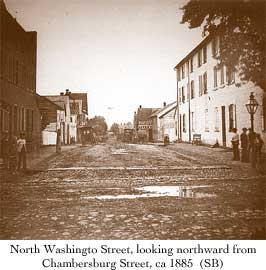

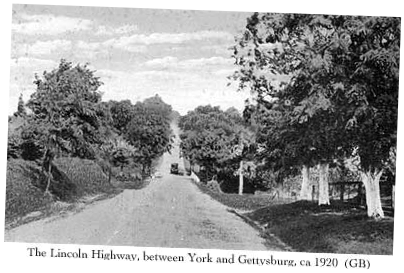

Highways remained high priority as the automobile became a viable mode of individual travel. The concept for a grand highway traversing the nation and connecting the east to the west coast gained in popularity. A sponsoring group of this plan seized on the Lincoln name and called themselves the Lincoln Highway Association.  This group submitted a plan to congress for a 3000 mile route to link the two coasts which would pass through Adams County and Gettysburg. In 1913 congress approved the plan creating the Lincoln Highway. Prosperity was projected for every community touched by this super highway in a way the coming of the railroad did sixty years earlier. In 1922 the macadamized surface of the Lincoln Highway(Route 30) in Adams County was complete.

This group submitted a plan to congress for a 3000 mile route to link the two coasts which would pass through Adams County and Gettysburg. In 1913 congress approved the plan creating the Lincoln Highway. Prosperity was projected for every community touched by this super highway in a way the coming of the railroad did sixty years earlier. In 1922 the macadamized surface of the Lincoln Highway(Route 30) in Adams County was complete.

This group submitted a plan to congress for a 3000 mile route to link the two coasts which would pass through Adams County and Gettysburg. In 1913 congress approved the plan creating the Lincoln Highway. Prosperity was projected for every community touched by this super highway in a way the coming of the railroad did sixty years earlier. In 1922 the macadamized surface of the Lincoln Highway(Route 30) in Adams County was complete.

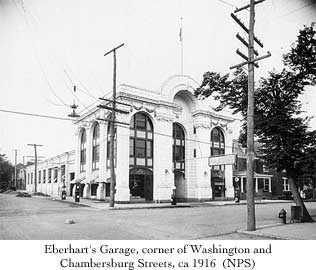

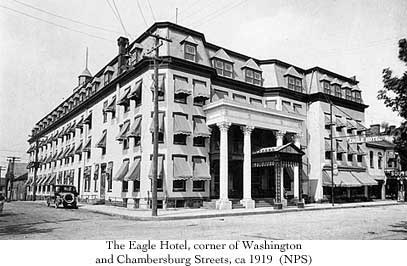

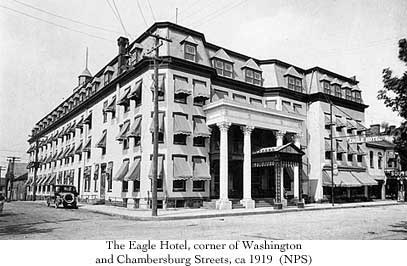

This group submitted a plan to congress for a 3000 mile route to link the two coasts which would pass through Adams County and Gettysburg. In 1913 congress approved the plan creating the Lincoln Highway. Prosperity was projected for every community touched by this super highway in a way the coming of the railroad did sixty years earlier. In 1922 the macadamized surface of the Lincoln Highway(Route 30) in Adams County was complete. As predicted motorist traffic to Gettysburg to visit the battlefield increased. Likewise, so did motorist through traffic heading east and west. This gave birth to new business opportunities as well as enriching those already existing to serve the needs of tourists.  Gas and service stations sprang up, mainly along York and Chambersburg Streets, the Lincoln Highway route through the center of town. These service stations were often part of new automobile dealerships or parking garages. It was a new market craze in town, and entrepreneurs jumped on the opportunity. Frank Eberhart, owner of the Eagle Hotel at the NE corner of Chambersburg and North Washington Streets converted his new theater building across the intersection at the SW corner to a garage-service station. Two blocks east at the NE corner of York and North Stratton Streets, Eddie Plank cashed in on his baseball fame and opened a dealership-garage. In between there were no less than five locations offering gas with pumps sitting right on the curb next to the street. Four of the these were located on both sides of the first block of York Street.

Gas and service stations sprang up, mainly along York and Chambersburg Streets, the Lincoln Highway route through the center of town. These service stations were often part of new automobile dealerships or parking garages. It was a new market craze in town, and entrepreneurs jumped on the opportunity. Frank Eberhart, owner of the Eagle Hotel at the NE corner of Chambersburg and North Washington Streets converted his new theater building across the intersection at the SW corner to a garage-service station. Two blocks east at the NE corner of York and North Stratton Streets, Eddie Plank cashed in on his baseball fame and opened a dealership-garage. In between there were no less than five locations offering gas with pumps sitting right on the curb next to the street. Four of the these were located on both sides of the first block of York Street. In that same stretch one could also buy a new Hudson or Chevrolet, park in a covered garage, or buy an engine tune up. The immediate, local fallout of the rise of a new automobile based industry was the final demise of the long standing carriage, harness, and livery professions. The up side was a sharp increase of visitation to the battlefield brought about by affordable automobiles and an improved national road system such as the Lincoln Highway.

In that same stretch one could also buy a new Hudson or Chevrolet, park in a covered garage, or buy an engine tune up. The immediate, local fallout of the rise of a new automobile based industry was the final demise of the long standing carriage, harness, and livery professions. The up side was a sharp increase of visitation to the battlefield brought about by affordable automobiles and an improved national road system such as the Lincoln Highway.

Gas and service stations sprang up, mainly along York and Chambersburg Streets, the Lincoln Highway route through the center of town. These service stations were often part of new automobile dealerships or parking garages. It was a new market craze in town, and entrepreneurs jumped on the opportunity. Frank Eberhart, owner of the Eagle Hotel at the NE corner of Chambersburg and North Washington Streets converted his new theater building across the intersection at the SW corner to a garage-service station. Two blocks east at the NE corner of York and North Stratton Streets, Eddie Plank cashed in on his baseball fame and opened a dealership-garage. In between there were no less than five locations offering gas with pumps sitting right on the curb next to the street. Four of the these were located on both sides of the first block of York Street.

Gas and service stations sprang up, mainly along York and Chambersburg Streets, the Lincoln Highway route through the center of town. These service stations were often part of new automobile dealerships or parking garages. It was a new market craze in town, and entrepreneurs jumped on the opportunity. Frank Eberhart, owner of the Eagle Hotel at the NE corner of Chambersburg and North Washington Streets converted his new theater building across the intersection at the SW corner to a garage-service station. Two blocks east at the NE corner of York and North Stratton Streets, Eddie Plank cashed in on his baseball fame and opened a dealership-garage. In between there were no less than five locations offering gas with pumps sitting right on the curb next to the street. Four of the these were located on both sides of the first block of York Street. In that same stretch one could also buy a new Hudson or Chevrolet, park in a covered garage, or buy an engine tune up. The immediate, local fallout of the rise of a new automobile based industry was the final demise of the long standing carriage, harness, and livery professions. The up side was a sharp increase of visitation to the battlefield brought about by affordable automobiles and an improved national road system such as the Lincoln Highway.

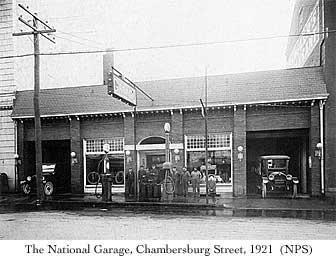

In that same stretch one could also buy a new Hudson or Chevrolet, park in a covered garage, or buy an engine tune up. The immediate, local fallout of the rise of a new automobile based industry was the final demise of the long standing carriage, harness, and livery professions. The up side was a sharp increase of visitation to the battlefield brought about by affordable automobiles and an improved national road system such as the Lincoln Highway. The growth in battlefield tourism after WWI was tremendous. Hotels responded by adding capacity. The demand on lodging brought about by the presence of the Lincoln Highway and proliferation of the automobile required it. The Hotel Gettysburg, under the management of young Henry Scharf, underwent a major addition for the second time in thirty years. In 1895 owner Robert Gilmore had added the third floor to the old McClellan House bringing the room capacity up to 70. Thirty years later the annex was built north of Race Horse Alley bringing the total rooms to 118. On the ground floor of the annex was a theater and an adjoining gymnasium/auditorium where the college team would play its home basketball games for a number of years.  All the hotels replaced their stable facilities with automobile parking. The Eagle Hotel had Eberhart’s across the street, and the Hotel Gettysburg, The Washington and Keystone Hotels had The National Garage in the first block of Chambersburg Street.

All the hotels replaced their stable facilities with automobile parking. The Eagle Hotel had Eberhart’s across the street, and the Hotel Gettysburg, The Washington and Keystone Hotels had The National Garage in the first block of Chambersburg Street.

All the hotels replaced their stable facilities with automobile parking. The Eagle Hotel had Eberhart’s across the street, and the Hotel Gettysburg, The Washington and Keystone Hotels had The National Garage in the first block of Chambersburg Street.

All the hotels replaced their stable facilities with automobile parking. The Eagle Hotel had Eberhart’s across the street, and the Hotel Gettysburg, The Washington and Keystone Hotels had The National Garage in the first block of Chambersburg Street. A new lodging concept appeared on the horizon driven by the same pressures behind the expansion of the traditional hotels. “Tourist cabins” offering informal convenience and a sense of privacy began to appear after 1930. They were on the outskirts of the town and catered exclusively to the automobile traveling tourists. Those still arriving via train took accommodations in the town hotels.

More and more private museums-souvenir shops opened to tap the ever increasing visitation. The museums featured relics and war material such as firearms and accoutrements allegedly picked up from the field or acquired directly from the veterans who fought here. The museum admission was free, serving as the “hook” to draw the tourist to the souvenir and refreshment counters. Almost every refreshment shop had a few relics hanging on their wall. Many of the larger collections featured items which were indeed authentic battle relics gathered with great care over the years. The Gettysburg National Museum, which George D. Rosensteel VI, opened in 1921 along the Taneytown Road, was the most complete and famous of the local collections. His uncle John’s collection, on display at his Round Top Museum on the Wheatfield Road, was one the earliest presentations of authentic battlefield relics. Elsewhere, the Clyde F. Daley collection in the Lee’s Headquarters house on Seminary Ridge, the Jenny Wade House Museum and the Shields Museum, where Route 30 crossed McPherson’s Ridge, were well known to tourists in this period. The Jenny Wade and Lee’s Headquarters Museums are the only survivors of that era still under private ownership.

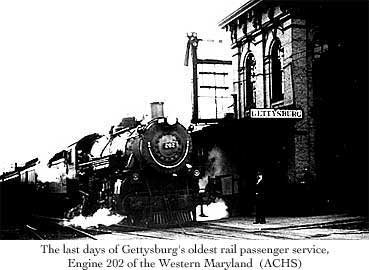

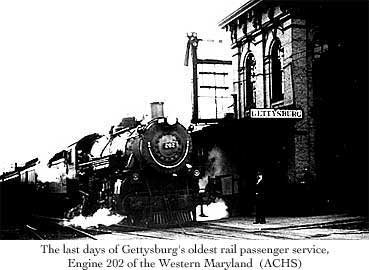

There was one major downside to the rise of automobile driving tourists, the erosion of passenger train revenues into Gettysburg. The 1920s and 30s saw the beginning of the near term end to that long time staple of the town’s economy, the passenger train service. In time the effect spread out and touched the demand for downtown hotel rooms when alternatives for automobile traveler’s lodging such as the new tourist cabins began to spring up. Within a decade the passenger service would disappear entirely. The town’s oldest rail passenger service, the Western Maryland, closed down permanently with the last train to Baltimore on New Year’s eve 1942. The last straw was the outbreak of WWII a year earlier which dramatically interrupted tourist visitation to the battlefield. The war only served as a catalyst to the inevitable. By the 1940s the automobile was king. The Western Maryland’s local rival line, the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad, shut down passenger service in 1947.

The town’s oldest rail passenger service, the Western Maryland, closed down permanently with the last train to Baltimore on New Year’s eve 1942. The last straw was the outbreak of WWII a year earlier which dramatically interrupted tourist visitation to the battlefield. The war only served as a catalyst to the inevitable. By the 1940s the automobile was king. The Western Maryland’s local rival line, the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad, shut down passenger service in 1947.

The town’s oldest rail passenger service, the Western Maryland, closed down permanently with the last train to Baltimore on New Year’s eve 1942. The last straw was the outbreak of WWII a year earlier which dramatically interrupted tourist visitation to the battlefield. The war only served as a catalyst to the inevitable. By the 1940s the automobile was king. The Western Maryland’s local rival line, the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad, shut down passenger service in 1947.

The town’s oldest rail passenger service, the Western Maryland, closed down permanently with the last train to Baltimore on New Year’s eve 1942. The last straw was the outbreak of WWII a year earlier which dramatically interrupted tourist visitation to the battlefield. The war only served as a catalyst to the inevitable. By the 1940s the automobile was king. The Western Maryland’s local rival line, the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad, shut down passenger service in 1947. While the dramatic events following WWI were forging economic changes in Gettysburg other aspects of town life went on as before. Segregation on multiple levels, namely education, occupation, public and social, continued to prevail. Schools were still not entirely desegregated, with segregation still existing in the six elementary grades. Beginning in 1923 students graduating from the segregated Franklin School could enroll at Meade School for the 7th and 8th or middle grades. Following graduation from Meade, black students went on to the high school which had been integrated since the late 19th century. Black leaders and parents led by Richard Thomas, who’s daughter Naomi was the first black female high school graduate, lobbied hard to eliminate the remaining racial segregation in the elementary schools. This goal was achieved in 1932, and the Franklin School was closed after 62 years of educating the town’s African American children. Since 1932 the Gettysburg public schools have been desegregated.

Job segregation did not improve as education did following the end of WWI. Improved educational opportunity did not lead to better employment opportunity. The barrier was racism which existed within the white community of Gettysburg just as it did throughout much of the country, north and south. The African American community in Gettysburg were better educated than they had been in the past, but were still limited to the semi skilled service and labor job scale. The increase in tourism created more low scale jobs, but not access to the higher pay jobs of direct customer service such as clerk or waitress. There was ample opportunity for cooks helper, laundry, porter and janitor. This barrier had the effect of discouraging a lot of young blacks, particularly males, from going on to high school and better preparing themselves. This situation would remain static for another twenty years before a coordinated grass roots push by black and white community leaders in Gettysburg would gain some concessions mitigating the racial bias in job opportunities.

Commercial services segregation for local and visiting African Americans was the most visible level of racial segregation in Gettysburg and elsewhere in those days. African Americans were not admitted as guests in the hotels, and in only a few of the restaurants. When an Afro American celebrity was invited to town to make an appearance he or she was dined and housed at the home of their host. Barber shops, beauty shops, bars, soda fountains and private service clubs all were segregated. Public places such as the hospital, courthouse and library, when it came into existence after WWII, were not segregated from use by African Americans. Nor were the retail stores and tourist shops in town. The merchants were more than willing to sell their goods to any and everyone, regardless of race or color.

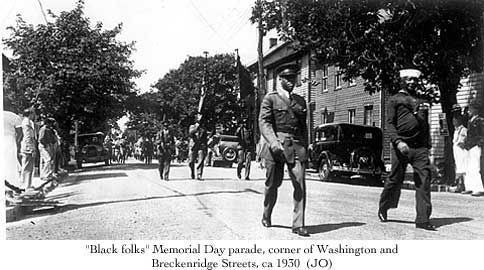

It was only natural that this level of community exclusion led to voluntary social separation, even in public commemoration events. The towns annual celebration of Memorial Day featured two parades. The “white people’s” parade down Baltimore Street and celebration of the dead buried in the Soldier’s National Cemetery, and the “black folk’s” parade. The latter featured honored, local, black veterans leading a parade up S. Washington Street to the remembrance and celebration of African American veterans buried in Lincoln Cemetery.

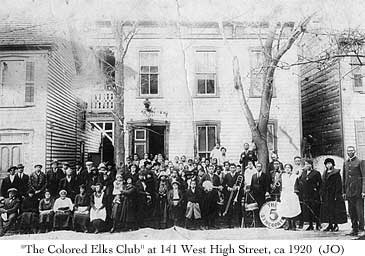

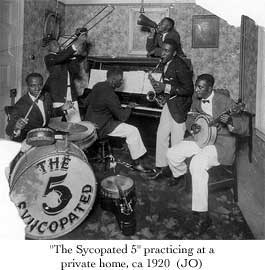

In the private arena they established their own “Colored Elks Club” at 141 West High Street, which became a family oriented social center for the African American community. Their evening dances were often accompanied by the “Syncopated Five,” a local group of very talented musicians specializing in a range of music including jazz, blues and “Dixieland.” The “Five” were appreciated by the entire community and were regularly hired by whites to play at social events, local clubs and beer halls.

The “Great Depression” was a condition that befell the nation in 1929 and lasted until the outbreak of WWII. The impact quickly shut down the nations densely populated manufacturing centers, leaving hundreds of thousands out of work. Gettysburg and Adams County were certainly impacted by the catastrophe, but far less drastically than many other areas and communities. The saving grace was it’s lack of economic dependency on heavy manufacturing. The county was still mainly an agricultural economy specializing in fruit, grain and vegetable production. Gettysburg was also favored with a diversified economy of light industry, tourism and professional services. All of these aspects of the local economy were impacted by the depression, but not to the extent the industrial centers of the nation were subjected. The town’s two main banks, the Gettysburg National and the First National Bank of Gettysburg were old and trusted institutions, and maintained the confidence of their depositors. They survived. Tourism was another saving grace. It too was impacted, but by no means eliminated by the nation’s economic woes. The automobile and good roads made Gettysburg easily accessible at a minimum of expense. A number of recessions since the Great Depression of the 1930s have bourne out the relative “recession proof” nature of Gettysburg’s tourist industry.

The politics of Gettysburg in the period between the wars under went some dramatic change. Immediately following the end of WWI there was a shift in voter support from the Democrats to the Republicans. The Democrats had gained a consistent edge in the late 19th century. On the local and county level a strong feeling of conservatism would prevail until the close of the 20th century. The character of the local politics also changed with the ending of the war. The passion of partisanship was still alive, but the expression of viewpoints and celebration of victory at the polls became less boisterous. The sharp and confrontational voices of the Sentinel and Compiler were toned down as were the wild victory celebrations. The voices of “Penelope Ann” and “General Meade” were silenced, and eventually committed as scrap metal to support the WWII war effort.

The largest “event” in Gettysburg during the between the wars years was the last joint reunion of the Union and Confederate veterans on the 75th anniversary of the battle in 1938. The event had it’s inception at the close of the 1913 reunion. The positive feelings of fellowship generated at the time led to a commitment by then Governor Tener to invite all surviving veterans of the civil war to return to Gettysburg in twenty five years for a “final” joint reunion. In 1930 preliminary plans got underway to fulfill that promise. Gettysburg’s John Rice, a state senator, took up the fight in the State Legislature and gained approval. A Pennsylvania State Commission was authorized and appointed by Governor George H. Earle. John Rice was appointed chairman. Dr. Henry Hansen, President of Gettysburg College, and Paul L. Roy, Editor of the Gettysburg Times were also named. Roy was appointed as the Executive Secretary. It fell to him to gain acceptance of the State’s invitation by the two veteran organizations, the GAR and the UCV. Despite the peace and harmony between the old vets demonstrated in 1913, there was enough personal bitterness remaining among veterans of both sides to block the proposed joint reunion. Between 1935 and 1937 Roy successfully sold and resold the approval from both UCV and the GAR. The latter turned out to be the most reluctant of the two groups to accept the invitation.

The last joint reunion was staged in Gettysburg, June 29th through July 6th 1938. The veterans, 1359 Union and 486 Confederate, arrived by train. They were housed in separate tent encampments on the north end of the Gettysburg College campus. Their average age exceeded 92 years. In 1913 when 55,000 veterans had attended, the reunion was administered by the War Department with the support of regular army troops. The War Department was replaced by the National Park Service in 1933 as the administers of the Gettysburg National Military Park. The NPS did not have the resources of the army at their disposal, so the Pennsylvania Commission, with the aide of a sister Federal Commission appointed by President Roosevelt, put the event together. Active U.S. Army units did participate in a five mile long parade through town and out to the college stadium, and in providing mock battle demonstrations which delighted veterans and visitors alike.

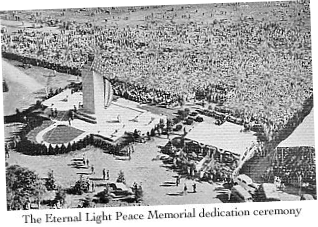

The highlight of the reunion events was the unveiling of the Eternal Light Peace Memorial on Sunday July 3rd. Like the 1913 reunion the keynote speaker was the President of the United States. President Roosevelt arrived by special train at the Gettysburg-Harrisburg station on North Washington Street. He had been here once before as President in 1934 to deliver the Memorial Day address at the Soldiers National Cemetery. He was the last of eight presidents to serve that honor and one of sixteen past and future presidents to visit Gettysburg and the battlefield.

Visitors to the dedication ceremony were estimated between 200,000 and 400,000. Whatever the correct number they constituted the largest one day crowd ever to assemble at Gettysburg. Their sheer numbers naturally overwhelmed the capacity of the town and the roads leading to it. As they did in 1863, and again in 1913, the citizens of Gettysburg coped with the inconvenience and did all they could to accommodate the visitors. Strangers were welcomed to sleep out on porch floors and furniture. Naturally many doors were opened to those same strangers when needing to use the bathroom or a bite to eat.

It was an especially exciting and profitable occasion for the town and it’s vendors of visitor related services. Certainly a welcome break from the doldrums of a decade long depression

In a greater and somber sense, it was the last time members of the titanic event that placed Gettysburg in it’s unique position of perpetual national prominence would meet each other on their original stage.

BETWEEN THE WARS