ANTEBELLUM:

1835 to 1860

By the end of the 1830s Adams County had completely shed itself of the last vestiges of it's "frontier" beginning. Gettysburg was thriving. It had successfully passed through its difficult years of adolescence on it's development scale. Socially, economically and physically Gettysburg was entering it's "mature" or "settled" phase. The quality of life had measurably improved for all facets of the population, although certainly not to the same degree.

The growing African American segment of the bottom economic-social stratum continued to be handicapped by the restraints of segregation found at this time in most areas of the state and the nation. Segregation in schools, quality of class room education, and job opportunity were the most limiting factors. Some few were able to break out of the caste and better their economic standing. Owen Robinson became a familiar proprietor of a confectionery shop, and later a restaurant featuring a raw oyster bar. Eden Devan began a long career speculating in rental and resale properties. Aside from these two and several other similar examples, the African Americans in town continued to be restricted to labor and service job opportunities.

By the mid 1840s there were eight established churches serving the spiritual and social needs of the varied ethnic segments of the town's population. The presence of two German Lutheran and one German Reformed churches measured the significant increase of people of German decent into Adams County, and Gettysburg in particular, since the turn of the century. While the Scotch-Irish relinquished their position as the dominate population segment, it was noted by Henry E. Jacobs that before the Civil War the Scotch -Irish Presbyterians remained the "dominate influence in town." Even so by the mid 19th century the Germans had made significant inroads in shaping the culture and political make-up of Gettysburg.

By the mid 1840s there were eight established churches serving the spiritual and social needs of the varied ethnic segments of the town's population. The presence of two German Lutheran and one German Reformed churches measured the significant increase of people of German decent into Adams County, and Gettysburg in particular, since the turn of the century. While the Scotch-Irish relinquished their position as the dominate population segment, it was noted by Henry E. Jacobs that before the Civil War the Scotch -Irish Presbyterians remained the "dominate influence in town." Even so by the mid 19th century the Germans had made significant inroads in shaping the culture and political make-up of Gettysburg. As the town matured the quality of life was improved by the opportunity to sacrifice some work time for socializing and entertainment. The churches played a major role in the form of sponsoring picnics and other types of social oriented gatherings. Calamities, such as barn fires, brought people together and provided a subject of conversation long after the flames were out. Traveling entertainment exhibitions came to town from time to time and attracted a heavy subscription from the town's citizens. Circuses were the most common of these attractions and were very popular. Gettysburg and its surrounding environs were prominent enough to attract a visit in 1849 from General Tom Thumb, the famous midget and nationally featured curiosity exhibit.

In 1842 the town was overwhelmed by an influx of visitors from around the county who came to see a balloon ascension. John McClellan, a part owner of the Franklin House (now the Gettysburg Hotel), became an instant hero-legend by accepting a challenge to ride the balloon into the sky and drifting away with the wind, seemingly lost beyond the horizon. He landed safely some miles away and returned triumphantly on horseback.

By the end of the 1850s the more affluent and gayer members of society were enjoying balls in McConaughy Hall and in the third floor hall of the new Sheads and Buehler building . A musical accompaniment was often provided by the band of the Gettysburg Independent Blues militia company.

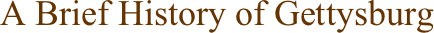

By the end of the 1850s the more affluent and gayer members of society were enjoying balls in McConaughy Hall and in the third floor hall of the new Sheads and Buehler building . A musical accompaniment was often provided by the band of the Gettysburg Independent Blues militia company. The public school system made noticeable improvements. The system of class rooms in numerous buildings dispersed around town was dropped in 1857 when the new, consolidated "Union School" building was erected on E. High Street . Besides consolidating classes, gender segregation was eliminated with boys and girls jointly attending classes in the new school.

Racial segregation was not eliminated. The African American school remained in a one story building equipped with home made desks and benches located two squares away in the SW corner of the intersection of W. High. and S. Washington Streets (later in the A.M.E. Church). The classroom sessions also remained unequal. The school year for the white students, boys and girls, was several months longer than those for the black students. This difference in time of yearly instruction obviously was a major factor in the dramatic inequity between the percent of white children determined to be illiterate(4.2%) versus that of black children(23.4%) in Adams County in 1850.

In 1854 the General Assembly created a position of County Superintendent of Schools to address the ills impacting the quality of schooling provided in the public schools.  David Wills was Adams County's first superintendent. He took action to improve teacher training and to increase pay in an effort to attract better instructors. Here again there was a noticeable inequality in the system. This time it directly impacted the teachers rather than the students. The male teachers averaged about $20 per month salary while female teachers were paid nearly $7 less. This inequity would wait another 100 plus years to be addressed on a national basis.

David Wills was Adams County's first superintendent. He took action to improve teacher training and to increase pay in an effort to attract better instructors. Here again there was a noticeable inequality in the system. This time it directly impacted the teachers rather than the students. The male teachers averaged about $20 per month salary while female teachers were paid nearly $7 less. This inequity would wait another 100 plus years to be addressed on a national basis.

David Wills was Adams County's first superintendent. He took action to improve teacher training and to increase pay in an effort to attract better instructors. Here again there was a noticeable inequality in the system. This time it directly impacted the teachers rather than the students. The male teachers averaged about $20 per month salary while female teachers were paid nearly $7 less. This inequity would wait another 100 plus years to be addressed on a national basis.

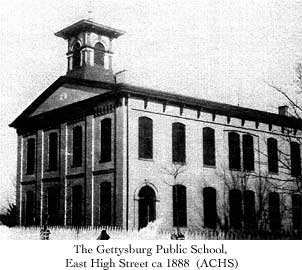

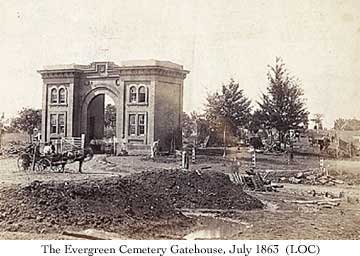

David Wills was Adams County's first superintendent. He took action to improve teacher training and to increase pay in an effort to attract better instructors. Here again there was a noticeable inequality in the system. This time it directly impacted the teachers rather than the students. The male teachers averaged about $20 per month salary while female teachers were paid nearly $7 less. This inequity would wait another 100 plus years to be addressed on a national basis. Between 1835 and 1860 the town development continued to explode to accommodate the ever increasing population. By 1860 there were 2400 inhabitants with 186(8%) being Afro Americans. The vast majority of town lots were committed to construction. Nearly 450 dwellings and other principal buildings existed by this time. The effect of this growth limited the expansion of the existing church cemeteries. A group of concerned leading citizens met in McConaughy Hall in November 1853 and determined that a new town cemetery was required. The Evergreen Cemetery Association was incorporated with David McConaughy named as the initial president. A stock subscription was initiated and seventeen acres procured on a prominent hilltop at the southern extreme of the town. It would come to be known as Cemetery Hill. The Association’s objective was to provide a site, "..in which the dead shall repose together without distinction of sect, rank or class." Race was not mentioned and the town's African Americans would continue to use their grave yard at York and Fourth Street.

A new cemetery was not the only facility driven by the impact of a growing population. The Adams County court house, residing in the center of the town square since 1804, was no longer adequate to deal with the demands coming from growth in the county and Gettysburg. In 1858 three existing dwellings were procured and removed in the south west corner of Middle and Baltimore Streets. In August of 1859 the new two story brick court house opened for court business. The old structure was razed and the brick used to build two new mansions on Carlisle St.

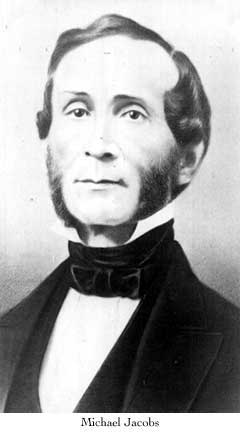

Improvements were not restricted to the raising of new buildings. A new gas company was organized to complement the already existing town water system as the latest innovation of leading edge technology usually found only in the largest metropolitan cities. Michael Jacobs a mathematics and science professor at the Pennsylvania College, was the creative force behind the Gas Company, and it's first president. This was a graphic illustration of the dynamic leadership benefitting the town because of the presence of a higher education institution.

Improvements were not restricted to the raising of new buildings. A new gas company was organized to complement the already existing town water system as the latest innovation of leading edge technology usually found only in the largest metropolitan cities. Michael Jacobs a mathematics and science professor at the Pennsylvania College, was the creative force behind the Gas Company, and it's first president. This was a graphic illustration of the dynamic leadership benefitting the town because of the presence of a higher education institution. Organized in January 1860 the company turned on their service in August that same year. In eight scant months a brick gas generating house had been built and equipped, two miles of iron main pipe buried beneath the streets, and two thousand feet of service line placed into customers’ buildings. The initial service lit up lamps at the town's major street intersections, student rooms at the college and seminary, and nearly fifty private dwellings.

Like other aspects of town life industry matured over the years. Individual craftsmanship was still prolific, but the cottage industry was evolving into a consolidated shop operation as an efficient means of manufacturing. By the 1840s carriage making had emerged as the leading industry and export trade. A number of craftsmen worked as subcontractors with the main carriage builders to produce a final product. Cabinetmakers, lace weavers, harness makers, wheelwrights, blacksmiths, silversmiths and painters all were involved in the production process, some of them working under one roof, usually a two story shop structure.

Gettysburg's first stand-alone factory was the steam foundry erected in 1834 by local entrepreneur George Arnold. In 1839 he was advertising in the Sentinel a line of cast iron products of machinery and farm equipment. In 1854 Charles W. Hoffman constructed his Steam Saw and Grist Mill just across the street from the older foundry. These two establishments marked a distinct contrast to the agricultural/craft nature of commerce historically dominating Adams County.

The major markets for Gettysburg's manufacturing production and merchant trading were Maryland and Virginia, easily accessible along established roads. The carriages and wagons went mainly to the southwest into Virginia via Hagerstown Maryland and on into the Shenandoah Valley. Fifty miles to the southeast was Baltimore where Gettysburg merchants found ample finished goods to stock their shelves. A strong market association and economic dependency developed with these two southern states, both strongly pro-slavery. This relationship would be severely strained during the 1860s by the Civil War, badly curtailing Gettysburg's war time and immediate post war economy.

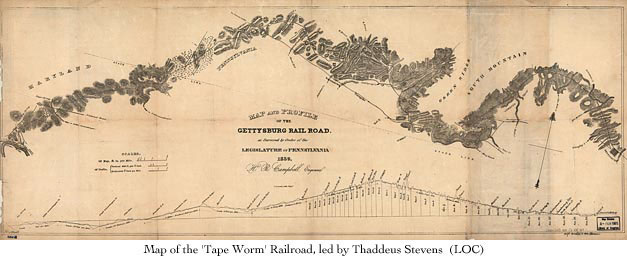

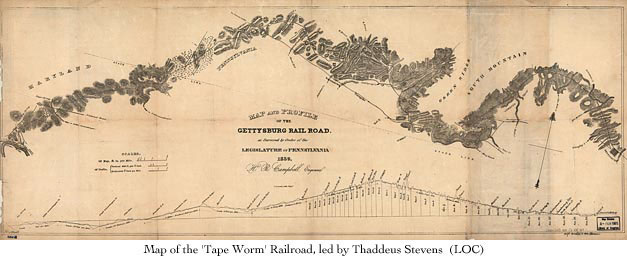

On December 16, 1858 Gettysburg and citizens from all over the county celebrated the single, most significant event in it's 72 year existence, the opening of rail road service. Twenty five years earlier the town leaders realized the necessity of tying into the nation's rail system if Gettysburg was ever going to permanently rise above a small country borough. Rail access to existing and future markets was a must to participate in a meaningful manner. In the early stages the dream looked obtainable. Local entrepreneur Thaddeus Stevens procured a State charter in 1835 to build a line to connect Wrightsville on the Susquehanna River to the B&O RR on the Potomac River west of Baltimore Maryland. The line was to pass through Gettysburg where workmen began laying out a track bed heading west. In 1838 Stevens lost the support of State grants and the project, nicknamed the "Tape Worm line,” had to be abandoned.

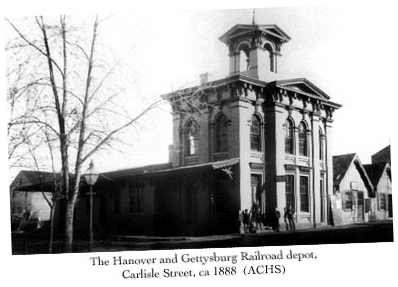

The dream was not abandoned. In 1850 three Gettysburg business leaders petitioned and won a grant from the state to build a rail road to connect Gettysburg to the existing Northern Central RR running between Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and Baltimore, Maryland. Selling subscriptions, mainly to the citizens of Adams County, took five years to raise the necessary capital with which to build the line. In February 1856 construction of the line between Hanover, Pa. and Gettysburg began. When it was finished almost three years later, the town's appearance was permanently changed. The Gettysburg Rail Road Company built a freight station adjacent to Stratton Street, an engine house and turntable a little to the east of the freight house, and a magnificent two story brick passenger station on Carlisle Street.

The dream was not abandoned. In 1850 three Gettysburg business leaders petitioned and won a grant from the state to build a rail road to connect Gettysburg to the existing Northern Central RR running between Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and Baltimore, Maryland. Selling subscriptions, mainly to the citizens of Adams County, took five years to raise the necessary capital with which to build the line. In February 1856 construction of the line between Hanover, Pa. and Gettysburg began. When it was finished almost three years later, the town's appearance was permanently changed. The Gettysburg Rail Road Company built a freight station adjacent to Stratton Street, an engine house and turntable a little to the east of the freight house, and a magnificent two story brick passenger station on Carlisle Street. Immediately upon the opening of the line in December 1858 both the passenger and the freight shipping business boomed. As a result the face of the town along the track line in North Street and extending a block north along Carlisle Street blossomed with new building construction. Four warehouses to handle the increased fright business were built between N. Washington and Stratton Streets. New housing went up along Carlisle Street north of North Street which heretofore had remained almost entirely open ground. The economic boon to the town and the county was significant from the outset.

Politics in Adams County and Gettysburg, at the local, state and national level, became a much more serious element of life and interest by the 1840s. The population had always joined in the debating process so fundamental to our democratic-republic form of government. In the early years strict partisanship was not the order of the day. The voting records in national elections confirms that a substantial majority of the county and the town were Federalist. This changed after the collapse of the Federalist party in the late 1820s. Jacksonian Democrats were pitted first against Whigs and then Republicans, the successors to the defunct Federalist party. The latter retained a slim majority of voter support in the county.

The closeness of the division between the parties in the county and the town naturally fostered an increase in the degree of partisanship underlying the political debate. The town's three weekly newspapers, The Sentinel (Whig/Republican), the Star (Whig/Republican) and the Compiler (Democrat) relentlessly fanned the flames of partisan debate in their editorial columns. While heated, often personal and nasty, and occasionally violent, the process of campaign debate was also an outlet for entertainment. Raucous torch light parades through the streets of Gettysburg ballyhooed the merits of candidate and ticket.

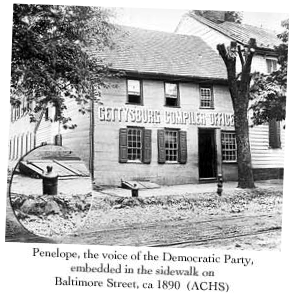

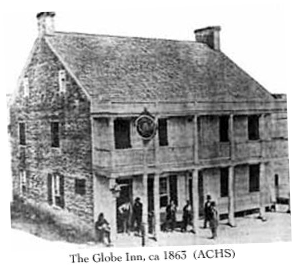

Victory was a cause for even louder celebration. The democrats had an old War of 1812 cannon, affectionately named "Penelope,” they loaded with powder and blasted off in the night to announce to anyone and everyone their ballot success. This activity was usually undertaken after an extended stay at their election headquarters set up in the tavern room of the Globe Inn.

Victory was a cause for even louder celebration. The democrats had an old War of 1812 cannon, affectionately named "Penelope,” they loaded with powder and blasted off in the night to announce to anyone and everyone their ballot success. This activity was usually undertaken after an extended stay at their election headquarters set up in the tavern room of the Globe Inn. In November 1855 the cannoneer suffered too much liquid preparation and overloaded "Penelope" with powder. The blast was extra loud, but too much for the old barrel which burst at the muzzle in the firing. "Penelope" was memorialized by being buried up to her breech in the pavement in front of the Compiler office at 126 Baltimore Street, where she reposes to this day. The burial site was chosen to visually signify the Compiler as the voice of the Democratic Party. The mourning of "Penelope" was short lived. She was quickly replaced with the "Penelope Ann" which survived until 1942, when she fell victim to a World War II scrap drive.

In November 1855 the cannoneer suffered too much liquid preparation and overloaded "Penelope" with powder. The blast was extra loud, but too much for the old barrel which burst at the muzzle in the firing. "Penelope" was memorialized by being buried up to her breech in the pavement in front of the Compiler office at 126 Baltimore Street, where she reposes to this day. The burial site was chosen to visually signify the Compiler as the voice of the Democratic Party. The mourning of "Penelope" was short lived. She was quickly replaced with the "Penelope Ann" which survived until 1942, when she fell victim to a World War II scrap drive. The propensity for county citizens to participate in political debate, while heated by the strong inclinations of partisanship, dragged the area into national political rift over issues which ultimately culminated in civil war. At the heart of the debate was the problem of what to do about slavery being practiced in the southern states. Gettysburg was no different from any other northern town in how they reacted to existence of this “peculiar institution.” They detested slavery, but also coexisted with free African Americans in a manner which demonstrated their inner feelings that blacks were inherently inferior. Thus, the racial segregation permeating all facets of Gettysburg's life. Early-on the town's intellectual leaders attempted to forge a "middle ground" position in the nation's debate over the solution to the "colored population." In the mid 1830s these highly educated and intelligent men including Thaddeus Stevens and the Rev. Samuel S. Schmucker, both avowed abolitionists, publicly advocated "African colonization" as a humane solution. The solution was vigorously debated locally as well as nationally, without gaining a majority acceptance.

More active solutions emerged while intellectual debate raged in public halls. The "underground railroad" by which blacks fleeing their masters were assisted in escaping to northern "free states,” passed through Adams County and possibly Gettysburg. Matthew Dobbin and Rev. Schmucker were both believed to have hidden fugitive slaves in their respective homes while sending them onto friendly way-stations down the line. A group of five leading African American citizens took action in 1840 to form the Slave Refugee Society. Under the chairmanship of Henry O. Chiller they drafted a constitution with a mission statement to aid all who came to them for the purpose of liberating themselves from "the tyrannical yoke of oppression." With the support of the church and its congregation the "Society" became active conductors along the road to freedom.

There was some danger involved in this task. Southern slave owners saw those abetting fugitive slaves as an evil enemy. A free, African-American Gettysburg woman, twenty one year old Maggie Palm, was probably the victim singled out by agents of slave holders for retaliation of past "conductor" activities by those in the local area. She was accosted on the street one night by two strangers in town who bound her hands and attempted to force her into a wagon for the purpose of carrying her back into Maryland. Once there she would have brought a large price for bondage. It never came to that. Her efforts to resist caught the attention of a fellow citizen who drove off her would be abductors and freed her.

There was some danger involved in this task. Southern slave owners saw those abetting fugitive slaves as an evil enemy. A free, African-American Gettysburg woman, twenty one year old Maggie Palm, was probably the victim singled out by agents of slave holders for retaliation of past "conductor" activities by those in the local area. She was accosted on the street one night by two strangers in town who bound her hands and attempted to force her into a wagon for the purpose of carrying her back into Maryland. Once there she would have brought a large price for bondage. It never came to that. Her efforts to resist caught the attention of a fellow citizen who drove off her would be abductors and freed her. The debate grew bitter at the national scale. Gettysburg and Adams county had very few supporters for the radical extremists, abolitionists and pro-slavery advocates. They voted at the national level in 1860 to elect Lincoln as a Republican president (by a county wide margin of six votes), while voting for the Democratic candidate for Governor of Pennsylvania. Like most in the north Gettysburg’s citizens were somewhat naive about the cause of the violent war that broke out within a month after the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln. They responded enthusiastically to the call to preserve the Union, not to the idea that they would be taking a stand to force an end to slavery.

As the year of 1860 drew to a close the citizens of Gettysburg were drawn to a more commemorative mood. The August 20th issue of the Compiler expressed the self congratulatory good feelings about what their town had become:

“Gettysburg now has her railroad, her water works, her gas works,

her cemetery, her college, her seminary, her large public school.

What will come next? We can not say, but our enterprising

little town never says stop.”

ANTEBELLUM