GETTYSBURG IN THE CIVIL WAR:

1861 to 1865

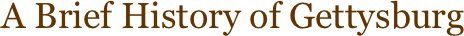

The attack on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor by South Carolina forces, and President Lincoln's call for volunteers to put down the rebellion marked the beginning of war. Gettysburg's home front response to those events and conduct relative to the evolving challenges and pressures of the ensuing struggle for the most part were typical of those of other northern towns. The exceptions were due to its' close proximity to the confederate border along the Potomac River. The frequent threat of enemy raids and the cry of the "the rebels are coming" was very unique to Gettysburg and other border areas in south-central Pennsylvania. Then, of course, there were the catastrophic events of 1863. The invasion and occupation of their town by enemy forces and the impact of destruction of property by three days of violent combat made Gettysburg's wartime experience, in this instance, more akin to that endured throughout the south than to their sister northern towns.

The patriotic response to Lincoln's call to arms was enthusiastically played out in the streets of Gettysburg. Two days after the firing on Ft. Sumter a bipartisan "Union Meeting" was held to denounce the secession of southern states and to pledge defense of the Union. The young men in town and county lined up in response to the President's call for ninety day volunteers. Impromptu patriotic speeches in the streets elicited enthusiastic support. It is quite probable that the booming voice of Penelope Ann was heard for the first time without a partisan political message.

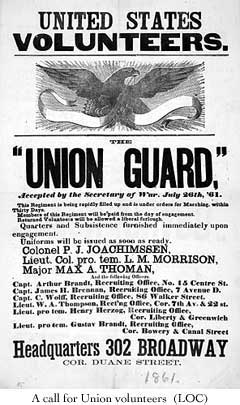

The patriotic response to Lincoln's call to arms was enthusiastically played out in the streets of Gettysburg. Two days after the firing on Ft. Sumter a bipartisan "Union Meeting" was held to denounce the secession of southern states and to pledge defense of the Union. The young men in town and county lined up in response to the President's call for ninety day volunteers. Impromptu patriotic speeches in the streets elicited enthusiastic support. It is quite probable that the booming voice of Penelope Ann was heard for the first time without a partisan political message. The Gettysburg Independent Blues, under the command of Capt. Charles H. Buehler, left the railroad station on April 21st, the first of Gettysburg's men to go off to war. Other units were quickly formed to provide town security and to await their muster into Federal service. The Adams Rifles and Gettysburg Zouaves were the initial units recruited. When it came time for these units to leave for the front they were given the same loud and emotional send off accorded the Blues a few months before.

Here again in Gettysburg, as in every other northern town, the prevailing racial segregation limited this patriotic enlistment to just the white males. In the initial stage of the war the African American citizens living in the northern towns and cities were not welcomed to fight against the forces of their current oppressors. This would change after Lincoln expanded the stated purpose of the war with the issue of his Emancipation Proclamation.

The rally to help the war effort was not only manifested in speeches and volunteering by patriotic males. The wives of the town's more prominent leaders quickly formed a Ladies Union Relief Society. They met weekly at the Methodist Church on E. Middle Street to make shirts, socks, "housewife" sewing kits and other items necessary to add to the comfort of living the military life in the field. Their efforts were mainly locally focused, directed to supporting Gettysburg and Adams County boys. There were some exceptions in the form of responses to special appeals to the town and county for a specific donation of food, clothing and the like. The Ladies Union Relief Association, under the leadership of Mrs. Robert G. Harper, took the coordinating role in these benevolent responses. It would be after their exposure to the battle experience in 1863 before the Relief Society shifted focus to the national need for their humanitarian support.

Local government stepped up to do its part. Men leaving job and home to go off to war left a financial burden on their families. The Gettysburg Borough council quickly appropriated a fund to provide $500 for the support of each citizen volunteer's family. The County government passed a measure adding to the pot.

After the initial outburst of patriotic enthusiasm the excitement abated and the routine of life adjusted to the wartime atmosphere. When the war's first grand battle at Bull Run ended in a Confederate victory instead of the end to armed hostilities the call for 300,000 more troops went out from the president. Again in the summer of 1862 the president twice more issued calls for 300,000 new volunteers. Nationally this was putting a huge strain on the available manpower. This time the response was less enthusiastic on the home front. Quotas were set for states, counties and boroughs. The concept of a federal draft to overcome the shortage of volunteers came under discussion. In Adams County the recruiters were offering cash incentives as early as the summer of 1861 and that practice continued for the duration. In short, money replaced patriotism as the motive to join up. Eventually a draft system did come into being. Gettysburg never failed to meet its assigned quota and never had to suffer a confrontation with it’s citizens which so often occurred with the implementation of the unpopular draft system.

A few days following Christmas in December 1861 the newly recruited 10th NY Cavalry Regiment, `The Porter Guards’, was sent to Gettysburg for winter quarters. They were placed here to establish a military presence along the southern border of Union territory. Confederate Virginia was a mere 60 miles south and the neutral, but largely pro-confederate, State of Maryland line was just 12 miles below Gettysburg. Barracks would not be erected a mile east of town until early February. Until then the garrison was quartered in large buildings, private and public, about the town. These included the court house, the Union School, the Sheads and Buehler building's 3rd floor ballroom, McConaughy Hall, George Schriver's ten pin alley and Dr. Study's carriage shop on West Middle Street. The regimental band was quartered in the RR station.

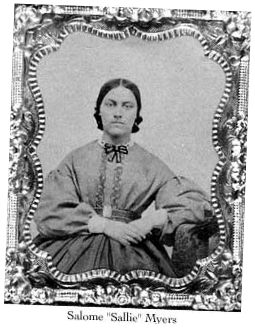

The town quickly warmed to the presence of the ‘Porter Guards'. They helped break up the monotony of the winter season with their daily parades, band concerts, and even boxing matches held in the center square. For the town's many eligible young ladies the Guard's presence brightened the social scene. After they departed in early March of 1862, Salome Myers, assistant principal at the Union School, most likely reflected the sentiments of a number of the town's young ladies when she sadly noted:)..." "It's just a week since the Porter Guards left Gettysburg. I am beginning to miss them, or rather Ed(Casey)...”

The town quickly warmed to the presence of the ‘Porter Guards'. They helped break up the monotony of the winter season with their daily parades, band concerts, and even boxing matches held in the center square. For the town's many eligible young ladies the Guard's presence brightened the social scene. After they departed in early March of 1862, Salome Myers, assistant principal at the Union School, most likely reflected the sentiments of a number of the town's young ladies when she sadly noted:)..." "It's just a week since the Porter Guards left Gettysburg. I am beginning to miss them, or rather Ed(Casey)...” By the time the ‘Porter Guards' arrived mean spirited political partisanship had returned to fill the vacuum left by the fading of the early fervor of patriotic unity in the town. Vitriolic exchanges over the conduct of the war by the Republican administration raged between Compiler publisher Henry Stahle and his by suggesting that they had been stationed here to censor his democratic political counterpart at the Sentinel, Robert G. Harper. Stahle tried to embroil the ‘Guards’ rhetoric. The commander of the Guards published an open letter in the Sentinel denying any interest in the "local dispute" between the partisan editors. The whole matter merely illustrated a return to normalcy in the political division among Gettysburg and Adams County citizens.

Like towns and cities all over the north and the south Gettysburg was exposed to the somber reality of war. Trains left the RR station with exuberant young men, hailed by throngs of well wishing fellow citizens, going forth on their great adventure. Soon, some were returning alone by those same trains in death, to be buried and mourned by their loved ones. As with their departure to the war front, their sad return was a matter of significant local news. One of the earliest to return was Frederick Huber, son of town physician Dr. Henry Huber. The June 28th 1862 issue of the Sentinel ran the sad headline with an emotional and heroic flair: “Our townsman, Frederick Huber, son of Dr. Huber, was killed near Richmond, shot through the lungs. "Tell my father I died for my country,” were his last words.” Young Huber was laid to rest in the family plot at Evergreen Cemetery.

Unlike the majority of northern towns the extended duration of the war had not brought on a booming economy for Gettysburg. It was just the contrary. Over the twenty years leading up to the outbreak of hostilities the leading element of the local economy was carriage manufacturing and its' associated crafts. The predominate market for this product line was in Virginia, now part of the Confederacy and cut off from trade with Gettysburg. Building construction, which was booming before Fort Sumter was fired upon, had all but ground to a halt for the duration. John and Valentine Werner the two brothers who built the RR station and related buildings in late 1858 went out of business three years later. Solomon Powers, Gettysburg's leading stone mason was practically idle throughout the war years.

Gettysburg was not a significant manufacturing center before the war unlike many sister towns in the New England region or the large eastern cities. Therefore, it could not convert its energies and limited facilities to making war materials as a substitute for its lost prewar economy. Alice Powers, daughter of Solomon, recalled, "..the busy shops were shut down." This statement was not a literal truth. All shops did not summarily close. Business was depressed, but the basic needs of town's ample population still existed, and as such merchants who could weather the depression kept up a lively hawking of their wares in the weekly newspapers.

During the first two years of the war Gettysburg along with other towns in Franklin County to the west and Cumberland County to the north were harassed by brushes with the fringes of the greater conflicts between the main opposing armies maneuvering in Virginia. This harassment came in the form of "raids" by marauding, real or imagined, Confederate forces. Most often these rather incidental intrusions were by small forces probing into the lower extremities of Franklin County in the abundant Cumberland Valley area. Only in October 1862 was Gettysburg realistically threatened, when rebel cavalry General `Jeb' Stuart led a division of his "regulars" into Adams County on his return from a raid through the Cumberland Valley and Chambersburg. The approach of this force was cause for alarm and anxiety among Gettysburg's citizens who were entirely defenseless. After pushing a patrol to within six miles to the west at present day McKnightstown, Stuart turned south at Cashtown into Maryland. The next day a regiment of Federal infantry arrived to mostly calm the nerves of the citizens.

Most often these raids heralded by panicked messengers from beyond South Mountain wildly claiming that, "the rebels are coming", were in fact false alarms, at least in the case of danger to Gettysburg. After awhile the white citizenry tended to ignore them or deal with them as a source of temporary excitement, a break in the daily routine. The reaction of the town's African American citizens was usually quite different. They knew if the rebels did come they would be in danger of being carried off to Virginia and subjected to slave labor. When the alarm was sounded they packed what they could carry and left home and town for nearby hideouts, such as the Yellow Hill Church community a dozen miles north or Wolf's Hill a secluded area just southeast of Gettysburg. The alarms and anxiety for this element of the community were a source of serious trauma not amusement.

The local political partisanship remained unabated despite both party's support for the war to restore the union. The Republican Party contained a radical element which vehemently supported abolition of slavery as a critical purpose of the war. Pennsylvania, and a majority of its' counties opposed slavery, but fell short of supporting abolitionism. Therefore, they voted for Democrat candidates in the 1862 elections. The state Republican Party changed its name to the Union Party in attempt to avoid the stigma of being identified as pro abolitionism. Gettysburg voted for Union candidates in Adams County elections in 1862 (though losing) and again in 1863 when they elected new borough officials. Stahle's editorials warned the community that the Union elected candidates and their supporters were really closet abolitionists whose sole aim was to prosecute the war to that end. This emotional issue remained on the front pages until the war's conclusion and beyond. The Sentinel denying that the Union Party favored abolitionism or the idea of keeping the war going until total defeat of the south could assure universal emancipation and equal rights for blacks. The Compiler relentlessly accusing the Republicans of doing just that. The town's voters continued to vote a bare majority to support the Union political philosophy, just the opposite of the rest of the county. Editor Stahle obviously had more influence with his readers outside the town than within.

The problem for the Union or Republican Party went far beyond just the abolition issue. The military setbacks, the federal Conscription(draft) Act, the need for increased taxation and central government control, coupled with Lincoln's controversial Emancipation Proclamation, all helped Democrats win support in the state and Adams County. As had been the case before the outbreak of war these issues were locally debated at a highly partisan level despite the continued agreement among both parties on the common objective of preserving the Union.

The approach of the two great armies into Adams County and the resultant battle at Gettysburg galvanized the town's citizens into a common experience that temporarily put aside all partisan political differences.

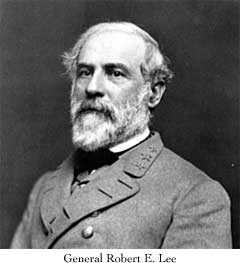

On June 12, 1863 Gov. Curtin sent out a bulletin alerting the citizens of Pennsylvania to the threat of possible invasion by General Robert E. Lee's daunted Army of Northern Virginia. Other notices soon followed calling on citizens to arm themselves and prepare for their own defense. Merchants in the border towns were advised to send their valuable goods to safer locations east of the Susquehanna River.  Sarah Broadhead kept a daily diary in which she noted on June 15th the arrival of the news in Gettysburg: "Today we heard that the Rebels were crossing the river(Potomac) in heavy force and advancing on this state. No alarm was felt until Gov. Curtin telegraphed a warning to people to move their stores."

Sarah Broadhead kept a daily diary in which she noted on June 15th the arrival of the news in Gettysburg: "Today we heard that the Rebels were crossing the river(Potomac) in heavy force and advancing on this state. No alarm was felt until Gov. Curtin telegraphed a warning to people to move their stores."

Sarah Broadhead kept a daily diary in which she noted on June 15th the arrival of the news in Gettysburg: "Today we heard that the Rebels were crossing the river(Potomac) in heavy force and advancing on this state. No alarm was felt until Gov. Curtin telegraphed a warning to people to move their stores."

Sarah Broadhead kept a daily diary in which she noted on June 15th the arrival of the news in Gettysburg: "Today we heard that the Rebels were crossing the river(Potomac) in heavy force and advancing on this state. No alarm was felt until Gov. Curtin telegraphed a warning to people to move their stores." Over the remainder of the month events played out rapidly which heightened the collective community anxiety to near the breaking point. The tension was made worse by the total absence of any information as to the where-about of the Union Army of the Potomac. Rumors abounded raising the familiar specter that "the rebels were coming." Salome Myers noted the mood and activity of the town in her diary: "The people did little more than stand along the street and talk. Whenever some one heard a new report all flocked to him. The suspense was dreadful... there was no social life in town at the time."

On June 22nd a group of townsmen encountered a patrol of confederate soldiers along the Chambersburg Pike just east of Cashtown eight miles distant. Now the truth was known, the rebels were actually coming. Merchants immediately loaded goods, records and cash on freight cars which had been leased to standby and sent them east to safety from the invading Rebels. Many male citizens began the trek on foot with their prized horses. The African American citizens once more packed their bags and left for points north and east, some going as far as Philadelphia and western New Jersey. Again Salome Myers' diary recorded the scene: "Darkies of both sexes are skedaddling and some white folks of the male sex...Oh dear, I wish the excitement was over."

Suddenly on Friday June 26th the Rebels arrived, galloping up Chambersburg Street with pistols discharging into the air and citizens scrambling to get behind closed doors. Gettysburg found itself occupied by Confederate forces for the first of what would be two times in a period of a week. They stayed until early Saturday morning after "buying" whatever merchant goods were left with their worthless confederate script. Their commander Maj. Gen'l. Jubal Early placed a demand for supplies with Borough President David Kendlehart, with an implied threat of retaliation on the town if the requested items were not forthcoming. Kendlehart tactfully explained that the demands could not be met due to the earlier evacuation of goods. Early accepted his explanation and the town was spared punishment.

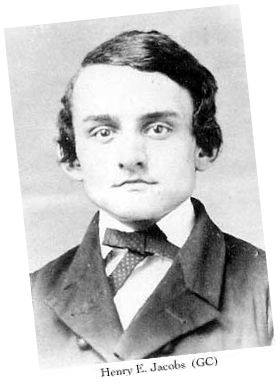

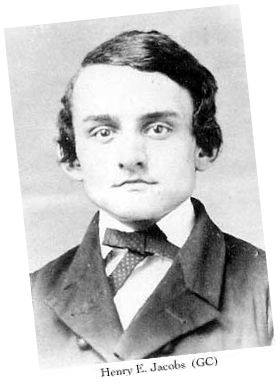

The Confederates had no designs on the town and were merely passing through on their way to York and beyond to the Susquehanna River. Despite the fact that a local farm boy, George Sandoe , a private in Capt. Robert Bell's newly formed Independent Cavalry was killed fleeing the enemy just south of Gettysburg, the citizens in town soon sensed that the Rebels meant them no harm. Some casual social interchange took place on the streets. It was noted that while they were dressed mainly in rags the Rebels were not the demons rumors had predicted. Henry E. Jacobs,

newly formed Independent Cavalry was killed fleeing the enemy just south of Gettysburg, the citizens in town soon sensed that the Rebels meant them no harm. Some casual social interchange took place on the streets. It was noted that while they were dressed mainly in rags the Rebels were not the demons rumors had predicted. Henry E. Jacobs, son of Professor Michael Jacobs, was favorably impressed: "Those Confederates were very businesslike in their attitude towards the townspeople, but were considerate enough.” Early's men did sever telegraph lines and burn the rail road bridge over Rock Creek one mile to the east, further isolating the town from outside communication.

son of Professor Michael Jacobs, was favorably impressed: "Those Confederates were very businesslike in their attitude towards the townspeople, but were considerate enough.” Early's men did sever telegraph lines and burn the rail road bridge over Rock Creek one mile to the east, further isolating the town from outside communication.

newly formed Independent Cavalry was killed fleeing the enemy just south of Gettysburg, the citizens in town soon sensed that the Rebels meant them no harm. Some casual social interchange took place on the streets. It was noted that while they were dressed mainly in rags the Rebels were not the demons rumors had predicted. Henry E. Jacobs,

newly formed Independent Cavalry was killed fleeing the enemy just south of Gettysburg, the citizens in town soon sensed that the Rebels meant them no harm. Some casual social interchange took place on the streets. It was noted that while they were dressed mainly in rags the Rebels were not the demons rumors had predicted. Henry E. Jacobs, son of Professor Michael Jacobs, was favorably impressed: "Those Confederates were very businesslike in their attitude towards the townspeople, but were considerate enough.” Early's men did sever telegraph lines and burn the rail road bridge over Rock Creek one mile to the east, further isolating the town from outside communication.

son of Professor Michael Jacobs, was favorably impressed: "Those Confederates were very businesslike in their attitude towards the townspeople, but were considerate enough.” Early's men did sever telegraph lines and burn the rail road bridge over Rock Creek one mile to the east, further isolating the town from outside communication. Any relief from tension and anxiety upon the departure of the Confederates was short lived. Lee's army was known to be in the vicinity, but nothing was known about the union forces who would protect them from possible destruction. The day following the departure of the Confederates a Union regiment of cavalry rode into town from Emmitsburg, Maryland. They assured every one that the entire Army of the Potomac was moving north through Maryland just several days march away. Again a wave of relief swept over the town. The cavalry camped outside of town and unceremoniously and quickly left at dawn the next day, Monday June 29th.

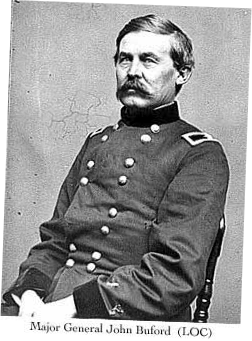

The town collectively sank back into a state of despair. Reports came in during the day from patrolling citizens that a great Rebel army was moving towards Gettysburg. Mid morning of June 30th enemy soldiers suddenly appeared on the crest of Seminary Ridge a half mile west of the end of Chambersburg Street. At almost the same instant a long column of Union cavalry could be seen approaching along the Emmitsburg Road. The Rebel force disappeared as the Union horsemen entered the town along South Washington Street.

The release of tension was immense. The citizens exploded in an impromptu celebration along the pavements as the troops rode into town. Maj. General John Buford's cavalry division of 3000 men seemed to the civilians as the whole Army of the Potomac. To a person they retired that night convinced that what everything was well. Catherine Foster spoke for many when she recalled: "..we thought the battle was as good as begun, fought and won." Young Albertus McCreary was more emphatic about the town's mood: "Not anyone thought that a great battle would be fought near us.” Evidence seems to indicate that the prevailing high level of anxiety and constant emotional ups and downs over the ensuing two weeks had cast a spell of denial among the townspeople. Fanny Buehler, who's post master husband David fled town earlier, probably had it right: "We were so used to the cry, “The rebels are coming!,” we paid little attention to it. When they really came we were unprepared for them.”

The next day, July 1st, the leading elements of two armies, collectively numbering over 150,000 men, met in combat a mile to the west and north of Gettysburg. This would be the first of three significant invasions, each involving thousands of people, with which the 2400 inhabitants of Gettysburg would have to cope in the next five months. Their collective response to these overwhelming events and the experiences they had to endure would serve to place this northern community apart from the home front experiences of all others living above the Mason and Dixon Line.

The day began in an attempt at normalcy for the citizens. By nine a.m. the sound of musketry and the roar of cannons washed away all such illusions. They were collectively stunned. Fear overtook a few and they hastily fled town to safer havens to the south and east. Many others were overcome by the fascination of the spectacle of battle and climbed to their roof tops to catch a glimpse of the deadly game playing-out beyond Seminary Ridge. The whizzing of spent missiles flying overhead soon brought a halt to this adventure. More sobering and practical activity began in the homes of several women, many who were members of the Relief Society. They gathered in groups and began picking lint to help with the treatment of the wounded they knew would soon be gathering in and about the town.

This would be the initial act in a huge humanitarian effort, voluntarily undertaken by a great many women in Gettysburg, which would last for several weeks. The task to which they dedicated themselves was the care and comfort of the wounded from both armies which flooded Gettysburg's buildings, both public and private, beginning in the mid morning hours of July 1st.

By 10 A.M. army surgeons were in Gettysburg looking for sites to set up hospitals. Practically on their heels was a ragged column of walking and assisted wounded. Many were arriving by the unfinished RR bed which paralleled the Chambersburg Pike westward through the battle zone. The large warehouse buildings and the RR station itself were the first chosen. They rapidly filled to capacity and more. As the fighting intensified with the arrival of more elements of both armies, the flow of Union wounded into town increased dramatically. They began to arrive into the lower ends of Chambersburg and W. Middle Streets looking for facilities providing medical aid.

The arrival of wounded in these areas brought about a wide spread encounter with civilians. Salome Myers succinctly recorded her initial reaction: "I grew faint with horror." Mary McAllister, living with her sister Martha and brother-in-law John Scott directly opposite Christ Lutheran Church on Chambersburg Street, experienced a similar wave of shock: "I did not know what to do."

Mary overcame the inertia of her shock quickly. She enlisted a neighbor, Nancy Wiekert and her niece Amanda Reinecker, and the three of them went across the street and opened the doors of the church , beckoning surgeons and wounded to enter. They stayed throughout the day administering pre and post operative care to the mangled men who filled the building to its capacity.

Soon after the doors of Christ Lutheran Church were opened the rest of the towns churches were quickly occupied. Then the public buildings, the courthouse and the Union School building. Before the end of the day Pennsylvania Hall at the college and the Lutheran Seminary building would be crammed with wounded from both armies. Still there was not enough room to accommodate the needy and private homes were opened to provide care and shelter. Red cloth, the universal symbol of a hospital, hung from upstairs windows throughout the town.

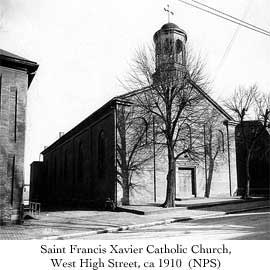

In all these locations the women of Gettysburg unhesitatingly and tirelessly gave of themselves to care for the wounded. Their work brought them face to face with ghastly, mutilating wounds and agony far beyond any previous experience in their family gender role of “Dr. Mom”. Their initial revulsion passed quickly and they persevered with grim determination. Salome Myers fled the hospital in the Catholic Church in W. High Street soon after entering as a volunteer nurse. She collapsed on the front steps uncontrollably convulsed with sobs. Slowly regaining her composure she reentered and embarked upon a two week stint without a break, caring for the helpless in the church and later in her home a half block to the west.

Late in the afternoon on July 1st the citizens were confronted with a sudden and terrifying experience. The Federal troops fighting to west and north of town began a sudden and disorderly retreat through the streets of Gettysburg toward Cemetery Hill just south of the Borough line. The victorious Confederates were in hot pursuit and flashes of intense fighting broke out in the streets and alleys as the pursued and pursuers moved from north to south through the town. Civilians fled to the safety of their cellars in a state of panic. They heard the shouts and discharge of weapons from above. Liberty Hollinger captured the moment and experience for all: "We watched through the cellar windows, and Oh, what horror filled our breasts as we gazed upon their bayonets and heard the deafening roar of musketry. Yes, we really were in the midst of an awful reality."

Almost as suddenly as it began the fighting in the streets was over, leaving a trail of shattered bodies and still corpses lying in the streets and backyards. The debris of dropped weapons and accouterments were everywhere as well as the occasional dead horse. Before the civilians could recover and emerge from their cellars Confederate soldiers were entering their houses looking for "Yankees" who choose to seek shelter as an escape from the risk of being slain in the crowded streets. This unwelcome invasion into the sanctity of their homes very quickly acquainted citizens with the "awful reality" that their town was occupied once again by the enemy. Alice Powers provided a fitting summary of the town's mind- set at the close of the day: “At night all was quiet, but the tramp of the guards reminded the town that its citizens were prisoners."

The town woke up the next day to find the Confederate battle line running east to west through the town. Several thousand troops made camp along Middle Street the night before. The southern end of town from approximately High Street south was a battle zone. Confederate sharpshooters occupied the several buildings in that area between Baltimore and S. Washington Streets. They dueled with union soldiers along the north slope of Cemetery Hill. The civilians living in that part of town had to remain in their cellars to avoid the deadly missiles during the daylight hours. They were constantly reminded of the danger upstairs by the tinkling of shattered glass and the dull thuds on the brick walls as bullets found their mark.

The town woke up the next day to find the Confederate battle line running east to west through the town. Several thousand troops made camp along Middle Street the night before. The southern end of town from approximately High Street south was a battle zone. Confederate sharpshooters occupied the several buildings in that area between Baltimore and S. Washington Streets. They dueled with union soldiers along the north slope of Cemetery Hill. The civilians living in that part of town had to remain in their cellars to avoid the deadly missiles during the daylight hours. They were constantly reminded of the danger upstairs by the tinkling of shattered glass and the dull thuds on the brick walls as bullets found their mark. In the northern half of town citizens were free to move about in relative safety from the bullets and found themselves interacting with their captors over life sustaining resources. At issue was food, water and outhouses (a municipal waste treatment facility was 70 years in the future). The facilities were adequate to support a population of 2400 not a number more than double that size. There was a shortage of everything, but the citizens willingly shared what they had, all of which was exhausted by the time the armies left.

Several times during the fighting during July 2nd and 3rd artillery exchanges flew over the town. When this occurred the citizens once again took to their cellars for protection. When the danger passed they could come out of hiding and move about freely. This was in contrast to their fellow citizens in the combat zone that was the southern end of town.

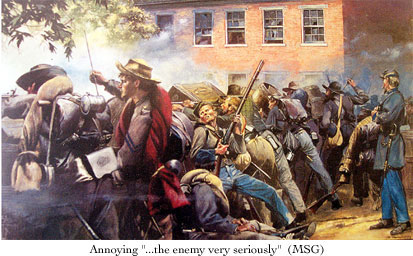

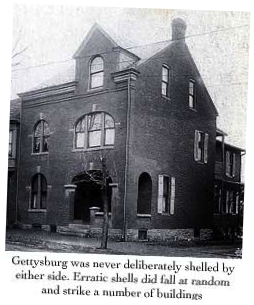

Despite rumors to the contrary Gettysburg was never deliberately shelled by either side. Erratic shells did fall at random and strike a number of buildings, a few more than once. No casualties were suffered from this random occurrence. There were two occasions when specific buildings in the town were targeted by Union cannoneers on Cemetery Hill. They were buildings sheltering annoying confederate sharpshooters who could not be effectively reached by rifle fire. One site was the 2 story carriage shop of Jacob Troxell on E. Middle Street. The other was the house of Jacob Stock on S. Washington Street. Both buildings were struck several times, successfully dislodging the enemy snipers and doing considerable damage to the owner's personal property.

On July 3rd, the living conditions and experiences for the citizens in the town were similar to those of the day before. There was one notable exception. Jennie Wade , staying at her sister's house on the north slope of Cemetery Hill, was accidentally killed by a bullet fired by a Confederate skirmisher. She was in the process of preparing bread for Union skirmishers stationed nearby the house when the errant bullet passed through two doors striking her in the back. She died instantly, her mother Mary standing near her side in the kitchen. Mary Wade, in obvious shock, walked into an adjoining room and announced to her older daughter, "Georgia, your sister is dead.” Jennie was the only civilian killed by the fighting at Gettysburg.

, staying at her sister's house on the north slope of Cemetery Hill, was accidentally killed by a bullet fired by a Confederate skirmisher. She was in the process of preparing bread for Union skirmishers stationed nearby the house when the errant bullet passed through two doors striking her in the back. She died instantly, her mother Mary standing near her side in the kitchen. Mary Wade, in obvious shock, walked into an adjoining room and announced to her older daughter, "Georgia, your sister is dead.” Jennie was the only civilian killed by the fighting at Gettysburg.

, staying at her sister's house on the north slope of Cemetery Hill, was accidentally killed by a bullet fired by a Confederate skirmisher. She was in the process of preparing bread for Union skirmishers stationed nearby the house when the errant bullet passed through two doors striking her in the back. She died instantly, her mother Mary standing near her side in the kitchen. Mary Wade, in obvious shock, walked into an adjoining room and announced to her older daughter, "Georgia, your sister is dead.” Jennie was the only civilian killed by the fighting at Gettysburg.

, staying at her sister's house on the north slope of Cemetery Hill, was accidentally killed by a bullet fired by a Confederate skirmisher. She was in the process of preparing bread for Union skirmishers stationed nearby the house when the errant bullet passed through two doors striking her in the back. She died instantly, her mother Mary standing near her side in the kitchen. Mary Wade, in obvious shock, walked into an adjoining room and announced to her older daughter, "Georgia, your sister is dead.” Jennie was the only civilian killed by the fighting at Gettysburg. When night fell, following the repulse of the final Confederate charge of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, the citizens detected a change in enemy morale. Up to this point no one knew what the outcome of the battle would be. This isolation from what was going on was a tangible source of rising anxiety among the citizens. On the night of the 3rd the despondent faces of the enemy gave a hint that Gettysburg might soon be liberated. Dawn on the following morning found the Confederates gone from the town and Union troops marching in along Baltimore Street. A subdued celebration was attempted by the exhausted population.

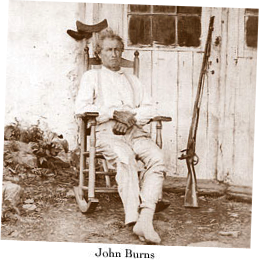

Lee's army had vacated the town, but remained entrenched along Seminary Ridge and among the Seminary buildings. Danger still lurked in the form of enemy sharpshooters along the base of Seminary Ridge. Four civilians received non-life threatening wounds on the streets of Gettysburg, probably all on July 4th. A fifth, John Burns , was wounded three times in the fighting on the Edward McPherson farm on July 1st. Burns an eccentric old man of 73, a veteran of the War of 1812 and former town constable, took his own musket out to the field and fought along side of the union Iron Brigade. The day following his wounding a neighbor brought him to his home where he recovered. Burn's became a national hero in the decade following the battle for his volunteer exploits.

, was wounded three times in the fighting on the Edward McPherson farm on July 1st. Burns an eccentric old man of 73, a veteran of the War of 1812 and former town constable, took his own musket out to the field and fought along side of the union Iron Brigade. The day following his wounding a neighbor brought him to his home where he recovered. Burn's became a national hero in the decade following the battle for his volunteer exploits.

, was wounded three times in the fighting on the Edward McPherson farm on July 1st. Burns an eccentric old man of 73, a veteran of the War of 1812 and former town constable, took his own musket out to the field and fought along side of the union Iron Brigade. The day following his wounding a neighbor brought him to his home where he recovered. Burn's became a national hero in the decade following the battle for his volunteer exploits.

, was wounded three times in the fighting on the Edward McPherson farm on July 1st. Burns an eccentric old man of 73, a veteran of the War of 1812 and former town constable, took his own musket out to the field and fought along side of the union Iron Brigade. The day following his wounding a neighbor brought him to his home where he recovered. Burn's became a national hero in the decade following the battle for his volunteer exploits.The fighting was ended between the armies and Lee began his retreat back to Virginia under the cover of darkness and a heavy rain storm on the night of July 4th. The last of General Meade's troops vacated the town on July 7th. The two armies left behind almost twenty one thousand wounded crowded in outlying field hospitals and in Gettysburg to be cared for by a mere handful of army surgeons. The town was left destitute of food and medical supplies.

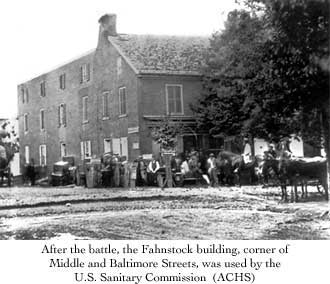

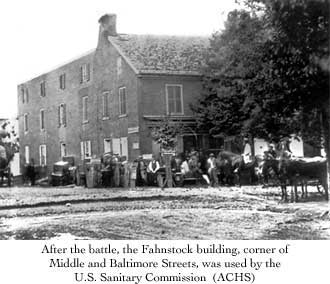

On July 10 the rail road bridge over Rock Creek was repaired and trains once more were bringing much needed supplies into the station. At the same time Gettysburg began feeling the overpowering effects of the second invasion by thousands of persons suffered in the past eleven days. This invasion did not involve warring armies. It was comprised of aid societies such as the U.S. Sanitary Commission, the U.S. Christian Commission , the Patriot Daughters of Lancaster and the Sisters of Charity from nearby Emmitsburg,, Maryland. All of these organizations were drawn here by the plight of the thousands of wounded. They were the first wave of relief for the beleaguered volunteer women of Gettysburg who had single handedly been serving the needs of the wounded since July 1st. Besides fresh hands, they brought with them food and medical supplies needed by wounded soldiers and civilians alike.

, the Patriot Daughters of Lancaster and the Sisters of Charity from nearby Emmitsburg,, Maryland. All of these organizations were drawn here by the plight of the thousands of wounded. They were the first wave of relief for the beleaguered volunteer women of Gettysburg who had single handedly been serving the needs of the wounded since July 1st. Besides fresh hands, they brought with them food and medical supplies needed by wounded soldiers and civilians alike.

, the Patriot Daughters of Lancaster and the Sisters of Charity from nearby Emmitsburg,, Maryland. All of these organizations were drawn here by the plight of the thousands of wounded. They were the first wave of relief for the beleaguered volunteer women of Gettysburg who had single handedly been serving the needs of the wounded since July 1st. Besides fresh hands, they brought with them food and medical supplies needed by wounded soldiers and civilians alike.

, the Patriot Daughters of Lancaster and the Sisters of Charity from nearby Emmitsburg,, Maryland. All of these organizations were drawn here by the plight of the thousands of wounded. They were the first wave of relief for the beleaguered volunteer women of Gettysburg who had single handedly been serving the needs of the wounded since July 1st. Besides fresh hands, they brought with them food and medical supplies needed by wounded soldiers and civilians alike. A second group of visitors arriving from all over the northern states were men and women searching among the wounded and buried for their loved ones. The third element in this invasion of visitors were curiosity seekers wanting to see a major battlefield and to pick up a souvenir from the discarded equipment literally blanketing the fields of combat. The cumulative effect of all these people was overwhelming to a town already reeling from the chaos and destruction of the great conflict of arms.

The town and its citizens persevered and by August some degree of normalcy returned. The number of total wounded remaining in Gettysburg and vicinity was down to five thousand and the vast majority of these were now in a new, consolidated hospital two miles east of town on the York Pike named Camp Letterman. The nearly sixteen thousand that had departed were shipped by railroad car to hospitals in the large eastern cities. Almost all the wounded were out of the private homes and churches save Christ Lutheran Church who kept its wounded into mid August. With the moving out of the wounded, churches quickly returned to serving the much needed spiritual needs of the community.

Unfortunately partisan political mean spiritedness reared its ugly head before the Union army had left the area. Henry Stahle, the vocal editor-publisher of the democratic Compiler, was accused of the treasonous act of aiding the enemy by an unidentified informant. Stahle had hosted a badly wounded union officer, Col Wm. W. Dudley of the Iron Brigade, in his home on July 1st. When Dudley's condition took a decided turn for the worse, Stahle went to the courthouse across the street and enlisted the services of a Confederate surgeon to come to Dudley's aid. The Dr. came escorted by Stahle and a Confederate soldier. Stahle's action saved Dudley's life. A prominent town Republican with obvious political credibility accused Stahle of leading the enemy to where they could capture the "hiding" Dudley. Stahle was arrested by the provost-marshal and sent under guard to Fort McHenry in Baltimore. There the authorities saw through the sham and returned Stahle to Gettysburg. His undisclosed accuser turned out to be political enemy and town neighbor,  David McConaughy.

David McConaughy.

David McConaughy.

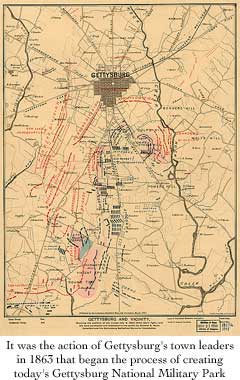

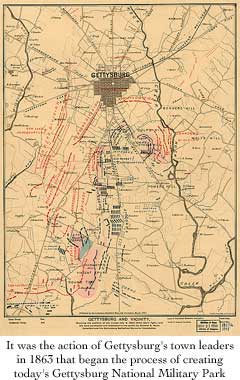

David McConaughy. That same David McConaughy turned out to be the person who's vision regarding the importance of the great Union victory at Gettysburg led to the existence of the present day Gettysburg National Military Park. McConaughy's vision was to memorialize the heroics of those who fought here by preserving the sites of the most significant fighting just as the army left them. He immediately used his own funds to take out purchase options on parts of Cemetery Hill, Culp's Hill and Little Round Top. He then asked his fellow townspeople to join him in this great undertaking. A large number accepted his appeal and the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) was founded. Thirty years later the GBMA would transfer its assets to the U.S. government as the foundation of the national park. Thus, it was the action of Gettysburg's town leaders in 1863, immediately following the battle, that began the process of creating today's Gettysburg National Military Park.

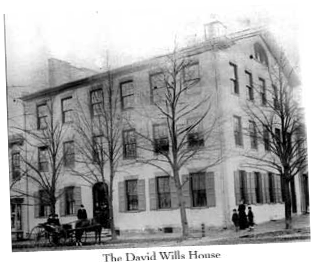

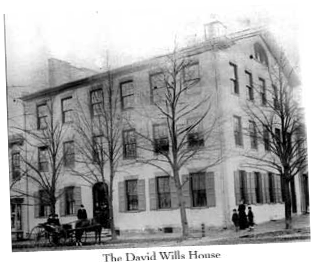

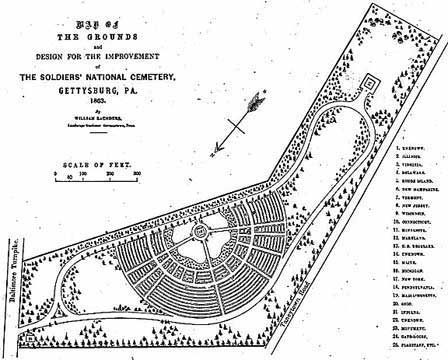

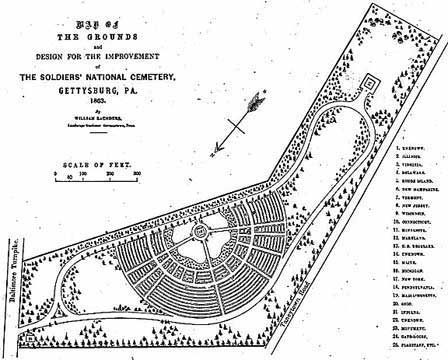

While McConaughy was pursuing his vision of the battlefield becoming a memorial, fellow Republican and neighbor David Wills was pursuing a vision of his own. Like McConaughy, Wills' pursuit would end up having a dramatic and lasting impact on Gettysburg and the nation as whole. Wills had been asked by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtain to represent him among a group of delegates from all the northern states who's men had fought and died at Gettysburg.  The delegates arrived at Gettysburg in late July, to examine the condition of the wounded and to determine what should be done with the nearly five thousand union dead who were spread over the field in hastily dug graves. The expense of exhuming these bodies, properly incasing them and transporting them to distant locations was too great for most families and their State treasuries. The high temperatures of mid summer demanded that the problem be quickly addressed. A meeting was held in David Wills’ house. A recommendation to create a common burying ground on the battle field to permanently house all the Union dead still buried around Gettysburg was agreed upon. It would be a State project requiring the consent of all the represented State governors for the necessary funding.

The delegates arrived at Gettysburg in late July, to examine the condition of the wounded and to determine what should be done with the nearly five thousand union dead who were spread over the field in hastily dug graves. The expense of exhuming these bodies, properly incasing them and transporting them to distant locations was too great for most families and their State treasuries. The high temperatures of mid summer demanded that the problem be quickly addressed. A meeting was held in David Wills’ house. A recommendation to create a common burying ground on the battle field to permanently house all the Union dead still buried around Gettysburg was agreed upon. It would be a State project requiring the consent of all the represented State governors for the necessary funding.

The delegates arrived at Gettysburg in late July, to examine the condition of the wounded and to determine what should be done with the nearly five thousand union dead who were spread over the field in hastily dug graves. The expense of exhuming these bodies, properly incasing them and transporting them to distant locations was too great for most families and their State treasuries. The high temperatures of mid summer demanded that the problem be quickly addressed. A meeting was held in David Wills’ house. A recommendation to create a common burying ground on the battle field to permanently house all the Union dead still buried around Gettysburg was agreed upon. It would be a State project requiring the consent of all the represented State governors for the necessary funding.

The delegates arrived at Gettysburg in late July, to examine the condition of the wounded and to determine what should be done with the nearly five thousand union dead who were spread over the field in hastily dug graves. The expense of exhuming these bodies, properly incasing them and transporting them to distant locations was too great for most families and their State treasuries. The high temperatures of mid summer demanded that the problem be quickly addressed. A meeting was held in David Wills’ house. A recommendation to create a common burying ground on the battle field to permanently house all the Union dead still buried around Gettysburg was agreed upon. It would be a State project requiring the consent of all the represented State governors for the necessary funding. David Wills immediately contacted Gov. Curtin and gained an enthusiastic approval. Curtin officially designated Wills as personal representative and assigned him the responsibility to implement the proposed undertaking. Wills attacked the task with vigor. He immediately selected an eight acre plot known as East Cemetery Hill only to discover that David McConaughy already had an option on the land for his battlefield memorial. Wills turned next to a twelve acre plot on Cemetery Hill only to discover that McConaughy had also arranged to purchase that land which adjoined the town's private Evergreen Cemetery. McConaughy, unaware of the state delegates plan, had acted on behalf of the Evergreen Cemetery Association. It was their plan the 12 acre plot be an addition to Evergreen with the idea of burying the Union dead in the town's cemetery.  Wills reacted with anger and apparently accused McConaughy of trying to profit through speculation and to derail his project. McConaughy immediately backed off and offered the desired Cemetery Hill 12 acre plot to Wills at his cost. Wills stubbornly refused and continued his accusation of McConaughy trying to profit from the situation. Governor Curtin broke the deadlock by soliciting the aid of two prominent Gettysburg citizens to mediate a resolution of differences.

Wills reacted with anger and apparently accused McConaughy of trying to profit through speculation and to derail his project. McConaughy immediately backed off and offered the desired Cemetery Hill 12 acre plot to Wills at his cost. Wills stubbornly refused and continued his accusation of McConaughy trying to profit from the situation. Governor Curtin broke the deadlock by soliciting the aid of two prominent Gettysburg citizens to mediate a resolution of differences.

Wills reacted with anger and apparently accused McConaughy of trying to profit through speculation and to derail his project. McConaughy immediately backed off and offered the desired Cemetery Hill 12 acre plot to Wills at his cost. Wills stubbornly refused and continued his accusation of McConaughy trying to profit from the situation. Governor Curtin broke the deadlock by soliciting the aid of two prominent Gettysburg citizens to mediate a resolution of differences.

Wills reacted with anger and apparently accused McConaughy of trying to profit through speculation and to derail his project. McConaughy immediately backed off and offered the desired Cemetery Hill 12 acre plot to Wills at his cost. Wills stubbornly refused and continued his accusation of McConaughy trying to profit from the situation. Governor Curtin broke the deadlock by soliciting the aid of two prominent Gettysburg citizens to mediate a resolution of differences. Wills purchased the land from the Evergreen Cemetery at McConaughy's original cost and proceeded to steer the creation of what is known today as the Soldiers National Cemetery. For his dedication and superb management of the implementation of the project he earned the unofficial title of the "founder" of the Soldiers National Cemetery.

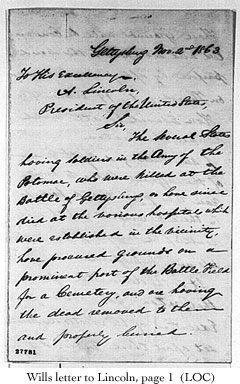

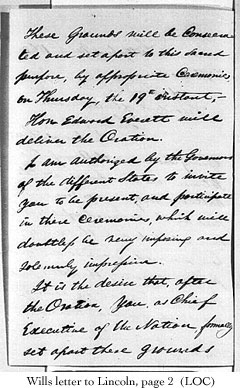

The official dedication of the still incomplete cemetery was set for November 19th, 1863. Despite the title "National Cemetery" this was not a federal project. The dignitaries initially invited to share the rostrum were not federal government people. Edward Everett was selected to be the main orator. At almost the last minute Wills took a chance on inviting President Abraham Lincoln to attend and to deliver a "few appropriate remarks" fitting to setting apart these sacred grounds. To the surprise of Wills and everyone else involved in the planning, Lincoln accepted the invitation. Thus, were the events set in motion which would culminate in the creation of an indelible bond between Abraham Lincoln and Gettysburg.

The dignitaries initially invited to share the rostrum were not federal government people. Edward Everett was selected to be the main orator. At almost the last minute Wills took a chance on inviting President Abraham Lincoln to attend and to deliver a "few appropriate remarks" fitting to setting apart these sacred grounds. To the surprise of Wills and everyone else involved in the planning, Lincoln accepted the invitation. Thus, were the events set in motion which would culminate in the creation of an indelible bond between Abraham Lincoln and Gettysburg.

The dignitaries initially invited to share the rostrum were not federal government people. Edward Everett was selected to be the main orator. At almost the last minute Wills took a chance on inviting President Abraham Lincoln to attend and to deliver a "few appropriate remarks" fitting to setting apart these sacred grounds. To the surprise of Wills and everyone else involved in the planning, Lincoln accepted the invitation. Thus, were the events set in motion which would culminate in the creation of an indelible bond between Abraham Lincoln and Gettysburg.

The dignitaries initially invited to share the rostrum were not federal government people. Edward Everett was selected to be the main orator. At almost the last minute Wills took a chance on inviting President Abraham Lincoln to attend and to deliver a "few appropriate remarks" fitting to setting apart these sacred grounds. To the surprise of Wills and everyone else involved in the planning, Lincoln accepted the invitation. Thus, were the events set in motion which would culminate in the creation of an indelible bond between Abraham Lincoln and Gettysburg.

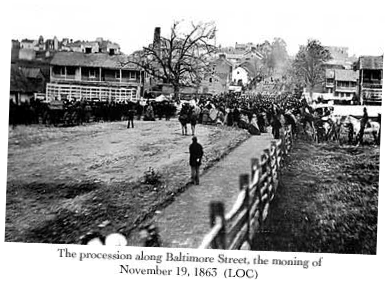

For Gettysburg the ceremony dedicating the Soldiers National Cemetery would trigger the third major invasion of thousands of people in the past six months. This time it was a joyous occasion for which the town had the opportunity to anticipate and prepare. Harvey Sweney wrote his brother, "Our old town roused up to action...every house groaned with good things to feed the coming crowd." And come they did, approximately twenty thousand of them from all over the country. Despite the plans and preparation Gettysburg was once more swamped by shear numbers of humanity. It was unusually warm for November and thousands of visitors without lodging roamed the street pavements in a party-like atmosphere.

President Lincoln and a small entourage of aides, cabinet members and politicians arrived at the RR station at approximately six pm on November 18th. The journey had taken six hours involving stops along the way in Baltimore, MD., Hanover Junction, PA. and Hanover, PA. Departing his coach the President was met by a party of state and town dignitaries and escorted up Carlisle Street the one block to the square and David Wills' house. Following a formal dinner Mr. Lincoln excused himself and retired to his bedroom on the second floor, presumably to put the finishing touches on his "few appropriate remarks" to be delivered at the cemetery dedication the following day.  Sometime before finally retiring for the night he did step out on the house steps in response to the pleas of the crowd only to inform them he had nothing to tell them that evening. Later he made a second appearance, to the delight of the boisterous masses, to walk next door to Robert Harper's house to confer briefly with Secretary of State William Seward. He made no formal comments to the crowd on this trip.

Sometime before finally retiring for the night he did step out on the house steps in response to the pleas of the crowd only to inform them he had nothing to tell them that evening. Later he made a second appearance, to the delight of the boisterous masses, to walk next door to Robert Harper's house to confer briefly with Secretary of State William Seward. He made no formal comments to the crowd on this trip.

Sometime before finally retiring for the night he did step out on the house steps in response to the pleas of the crowd only to inform them he had nothing to tell them that evening. Later he made a second appearance, to the delight of the boisterous masses, to walk next door to Robert Harper's house to confer briefly with Secretary of State William Seward. He made no formal comments to the crowd on this trip.

Sometime before finally retiring for the night he did step out on the house steps in response to the pleas of the crowd only to inform them he had nothing to tell them that evening. Later he made a second appearance, to the delight of the boisterous masses, to walk next door to Robert Harper's house to confer briefly with Secretary of State William Seward. He made no formal comments to the crowd on this trip. The ceremonies began the next day with a parade along Baltimore Street to the dedication site on Cemetery Hill. Lincoln in his signature dress of black suit, overcoat and stove pipe hat rode along with other dignitaries and parade marshals. The bands, military units and lesser dignitaries walked while thousands thronged the pavements along the route.  The speakers platform stood on the highest point on the crest of Cemetery Hill at a spot which is actually just within the Evergreen Cemetery property. The crowd stood in front in a semi circle, mostly on the National Cemetery grounds.

The speakers platform stood on the highest point on the crest of Cemetery Hill at a spot which is actually just within the Evergreen Cemetery property. The crowd stood in front in a semi circle, mostly on the National Cemetery grounds.

The speakers platform stood on the highest point on the crest of Cemetery Hill at a spot which is actually just within the Evergreen Cemetery property. The crowd stood in front in a semi circle, mostly on the National Cemetery grounds.

The speakers platform stood on the highest point on the crest of Cemetery Hill at a spot which is actually just within the Evergreen Cemetery property. The crowd stood in front in a semi circle, mostly on the National Cemetery grounds. After Edward Everett finished his lengthy oration, Mr. Lincoln arose. Henry Jacobs stood nearby and clearly recalled what happened next: "He reached in his side pocket and drew out an old metal spectacles case. He put a low pair of glasses before his eyes. Then reaching again into his pocket he drew out a sheet of paper considerably crumbled. Then he arose with his glasses at the tip of his nose.” The President stepped before the podium and in his clear, high-pitched voice delivered his "few appropriate remarks." Those words, known throughout the world today as the "Gettysburg Address," resonate the concept and meaning of freedom under a democratic government. The brevity in contrast to Everett's long oration caught the crowd by surprise. They waited for the president to continue. Then slowly the applause built to an expression of warm appreciation.

The president returned to the Wills house and asked to meet the local hero-legend John Burns. When Burns arrived Lincoln insisted that he accompany him to the Presbyterian church to attend an Ohio sponsored republican political rally. They shared a pew for the program. When it was over President Lincoln returned to the Wills house before departing for the railroad station and boarding his waiting train to return to Washington. He was in Gettysburg only twenty four hours, but established an association with the town which will never perish.

The president returned to the Wills house and asked to meet the local hero-legend John Burns. When Burns arrived Lincoln insisted that he accompany him to the Presbyterian church to attend an Ohio sponsored republican political rally. They shared a pew for the program. When it was over President Lincoln returned to the Wills house before departing for the railroad station and boarding his waiting train to return to Washington. He was in Gettysburg only twenty four hours, but established an association with the town which will never perish. The long term effect of the events of July and November on Gettysburg and its citizen were few, but significant. The immediate challenge was to return to normalcy. With a few exceptions that was accomplished in fairly short order. No great changes took place in gender roles despite the humanitarian heroics of the town's women, or in the African American's status in the community. The old social, political and economic order remained in place.

One significant change did occur in Gettysburg, not directly impacted by the battle. In 1863 the federal government was ready to accept African Americans into the military service. The U.S. Colored Troop (USCT) was created. Following the battle many young Gettysburg African American men volunteered and served with distinction through the remainder of the war. Seven would suffer combat wounds in various engagements and one, Fleming Devan, would be killed in action at the battle of Olustee, Florida.

One significant change did occur in Gettysburg, not directly impacted by the battle. In 1863 the federal government was ready to accept African Americans into the military service. The U.S. Colored Troop (USCT) was created. Following the battle many young Gettysburg African American men volunteered and served with distinction through the remainder of the war. Seven would suffer combat wounds in various engagements and one, Fleming Devan, would be killed in action at the battle of Olustee, Florida. The African American element of Gettysburg's population was probably disturbed the most by the Confederate invasion. Many who left and found their way to the Philadelphia area and other far reaching areas apparently did not return. These were people who did not own property. All of those who did own their homes returned. Many like Sophia Devan, who's house stood in the fork of Taneytown and the Emmitsburg Roads, found their houses badly damaged by battle and/or ransacked by soldiers. This was not a racial issue. The flying missiles were indiscriminate and the Rebels looted all houses that were abandoned by their owners without consideration of race. The net effect was a reduced population in the African American community after the battle. The black community would recover in numbers by the end of the decade, but a minority of those (31%) would be persons living in Gettysburg before July 1863.

The events of July and November 1863 did leave one other indelible and dramatic change on the town and it's citizens. Gettysburg became an instantly recognizable name on the national scene. It was where the union forces finally turned the tide of defeat in the eastern theater into victory. It was where Abraham Lincoln so succinctly and clearly redefined the meaning of freedom and our constitution. Gettysburg was aware of the of this new national status. The twenty six town leaders who joined David McConaughy in creating the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association consciously moved to establish a physical reminder of the heroic achievements of those who fought to preserve the Union. Their public statement published in the Sentinel on August 19, 1863 responding to David McConaughy's appeal makes this very clear.

"We entertain...the sentiment that these memorable battles...

in which the arms of the United States were crowned

with signal victory...deserve commemoration...in every way

such triumphs can be consecrated...Fought, as they were, in

defense of Republican Government and well regulated Freedom,

these battle fields are adapted to perpetuate the great

principles of human liberty and just government in the minds

of our descendants, and all men who in all time shall visit them."

Almost from the moment the guns fell silent on the field there was born a mystic attraction between the physical site of the battle and the psyche of the American people. Between July 1863 and the end of the war in April 1865 a steady trickle of visitors came from northern states to see the great field on which the war's most significant battle had been fought.

Within Gettysburg's citizens there was an intangible sense of bonding with a national purpose. This new awareness clearly manifested itself in the expanded activities of the local benevolent aid societies. No longer were boxes of food and other necessities prepared just for the comfort of local citizen-soldiers. There were enthusiastic responses to requests for support from the US Sanitary and Christian Commissions through out the remaining twenty months of the conflict following the events of July 1863.

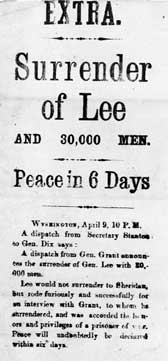

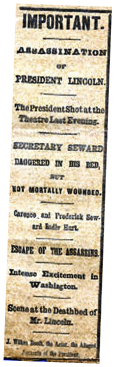

Local politics marked by vehement partisanship quickly returned to the scene. The slavery issue, now fully exposed on the national scene as a foremost objective of prosecuting the war, was the main issue of debate. Both sides avoided being associated with the extremists. Editor Harper of the Sentinel denied any sympathy with the abolitionists. Stahle was just as vehement that he and the democrats were not pro-slavery. The Compiler instead aimed its charges that the Republicans wanted to keep the war going beyond the natural time to end it for the sole purpose of ensuring blacks racial equality and the right to vote. The news of Lee's surrender and Lincoln's assassination silenced the editorial bickering and all people rejoiced and then mourned. Then attention turned to returning to a peacetime environment.

GETTYSBURG IN THE CIVIL WAR