THE COLONIAL PERIOD:

1735 to 1786

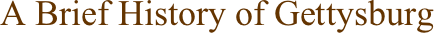

John Steelman , a European from Lancaster County, is thought to be the first permanent resident in what would become Adams County. Perhaps as early as 1718 he established a trading post in modern day Zora, 14 miles southwest of Gettysburg. The area was not officially acquired from the Native Americans by the Penns until 1736, after which European settlement started in earnest, followed by a sufficient number of families clearing the land and setting up homesteads to reclassify the area from wilderness to frontier. By the late 1730s the southern region of Pennsylvania was considered settled to the Susquehanna River, with the frontier extending westward as far as the mountains bordering the western area of future Adams County. Land beyond these mountains remained classified as “wilderness.”

John Steelman , a European from Lancaster County, is thought to be the first permanent resident in what would become Adams County. Perhaps as early as 1718 he established a trading post in modern day Zora, 14 miles southwest of Gettysburg. The area was not officially acquired from the Native Americans by the Penns until 1736, after which European settlement started in earnest, followed by a sufficient number of families clearing the land and setting up homesteads to reclassify the area from wilderness to frontier. By the late 1730s the southern region of Pennsylvania was considered settled to the Susquehanna River, with the frontier extending westward as far as the mountains bordering the western area of future Adams County. Land beyond these mountains remained classified as “wilderness.” The rate of migration of settlers into this area was impacted a long term boundary dispute between the William Penn heirs and the Calverts of Maryland. The dispute was generated by the apparent contradiction of language describing the location of the dividing line in the two "Royal Grants" issued to George Calvert and William Penn. At stake was a fifty mile wide strip running from the Delaware River 250 miles west. The Penns' claim would annex the northern half of Maryland including the port city of Baltimore. The Calverts' felt that their grant extended to a line which encompass most of Adams County and would include the southern half of present day Philadelphia.

The rate of migration of settlers into this area was impacted a long term boundary dispute between the William Penn heirs and the Calverts of Maryland. The dispute was generated by the apparent contradiction of language describing the location of the dividing line in the two "Royal Grants" issued to George Calvert and William Penn. At stake was a fifty mile wide strip running from the Delaware River 250 miles west. The Penns' claim would annex the northern half of Maryland including the port city of Baltimore. The Calverts' felt that their grant extended to a line which encompass most of Adams County and would include the southern half of present day Philadelphia. Both parties believed that actual occupancy of the disputed territory would be a deciding factor in any settlement. In 1734 the Penns' authorized their agent to begin issuing "licenses" to occupy and title land in the disputed area if the settler pledged to recognize Pennsylvania's provincial government. The Calverts also encouraged settlement by Marylanders. This action did little to resolve the dispute, but did accelerate the westward migration in Pennsylvania and a rush of Marylanders from the south. The immediate fallouts were violent land disputes, when coupled with England’s King’s order to both parties to settle the matter, served to force the Calverts and Penns to a negotiated resolution. Two Englishmen, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon , were engaged to survey the agreed upon boundary. They began in 1763 and finished 1767, after marking their 244 mile line at five mile intervals with "crown stones" and "mile stones" in between.

Both parties believed that actual occupancy of the disputed territory would be a deciding factor in any settlement. In 1734 the Penns' authorized their agent to begin issuing "licenses" to occupy and title land in the disputed area if the settler pledged to recognize Pennsylvania's provincial government. The Calverts also encouraged settlement by Marylanders. This action did little to resolve the dispute, but did accelerate the westward migration in Pennsylvania and a rush of Marylanders from the south. The immediate fallouts were violent land disputes, when coupled with England’s King’s order to both parties to settle the matter, served to force the Calverts and Penns to a negotiated resolution. Two Englishmen, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon , were engaged to survey the agreed upon boundary. They began in 1763 and finished 1767, after marking their 244 mile line at five mile intervals with "crown stones" and "mile stones" in between. Scotch-Irish immigrants led the migration from the Philadelphia area west to settle the future Adams County. They were driven by the lure of available land, remote from the immediate oversight of provincial government and religious persecution. They arrived in central Adams county and settled along the Marsh and Conewago Creeks, staking out their 100 acre plots and building substantial Presbyterian churches. Their quality of life along the frontier was one of hardship. Survival in the unsettled area depended on subsistence farming. Cash crops would come much later. Their thoughts were said to be "divided between bread in this world and heaven in the next."

These "homesteaders" were clearing woods and tilling land historically used by Native Americans for tribal hunting grounds. The "settlement" naturally infringed on this ancient rite of the natives. Hard feelings were occasionally aroused, but the atmosphere remained generally peaceful. When the Native Americans sided with the French in 1854 in their territorial dispute with the English a new and cruel challenge faced the settlers. The heretofore peaceful relationship with Native American tribes turned hostile and dangerous.

Beginning in 1755 marauding bands of Indians, sometimes accompanied by their French allies, conducted random raids on family homesteads among settlers beyond the Marsh Creek in western areas of present day Adams County. The constant fear of loss of life and property ended with the cessation of hostilities in 1763.

As the number of settlers in Adams County grew the area became more settled and the people more prosperous. The needs for goods and market outlets became prominent. Lacking navigable water bodies to reach established market centers and grinding mills created a demand for overland transportation. Frontier paths would not suffice. As early as the 1740s Adams County settlers were petitioning Lancaster and then York County courts for the construction of roads into their area. The first one approved connected the Susquehanna River to the Potomac River in Maryland. Named the Monacacy Road it passed through Hanover and Littlestown in southern Adams County on route through Taneytown and Frederick in Maryland. Marylanders referred to it as the "Great Wagon Road to Lancaster." In the spring of 1747 the second public road in the county, “Black's Gap Road," came west from York and passed eight miles north of the future site of Gettysburg on its way to the Cumberland Valley. In the fall of 1747 a third road through the county was approved creating the Nichol's Gap Road, later known as the Hagerstown Road, connecting with the Black's Gap Road at New Oxford and passing through the future towns of Gettysburg and Fairfield before winding its way through South Mountain into the Cumberland Valley, eventually accessing Hagerstown Maryland and the shores of the Potomac River leading to Virginia's Shenandoah Valley.

Adams County's mid-state location placed it a considerable distance from the market center of Philadelphia. The Susquehanna River was a significant barrier to eastward travel despite the existence of major public roads. Baltimore Maryland was far more accessible, being only 50 miles away and a major deep water port. Settlers in Adams County and adjoining Cumberland County to the north were clamoring for a road to link them to the market at Baltimore. A petition pleaded their case "to carry the effects of their labor to the Baltimore market". By 1769 the ensuing road from Shippensburg led south through Mummasburg and crossed the Nichol's Gap Road at the future site of Gettysburg before passing south east through Littlestown into Maryland and on to Baltimore.

Travel along the new roads demanded accommodations for rest and refreshments. Inns or taverns popped up along the roads about every 8 to 10 miles, the distance normally traveled in a day. Besides serving weary travelers the inns unofficially served as a community center where public notices were posted and public business was often transacted. Not surprisingly other service functions, such as blacksmith shops and stores, located around the inn. Houses followed to serve the merchants. In short, many of the initial villages in Adams County sprang up around a tavern stop. John Abbott's tavern led to the founding of Abbottstown. Frederick Kuhn's tavern spawned New Oxford, as did Michael Miller's inn become Millerstown, later Fairfield. And, of course, so did Samuel Getty's tavern at the intersection of the Nichol's Gap and Baltimore Roads eventually evolve into a community named after the old innkeeper's son, James.

The creation of towns meant that the frontier of sparsely located homestead settlers was giving away to the more advanced state of settlements. By the eve of the American revolution the frontier line had passed well to the west of the Marsh Creek settlement. Sides over the issue of loyalty to the crown or to the patriot's call to break with Great Britain was sharply divided in Pennsylvania. In the older, established eastern counties and the City of Philadelphia, where passive Quakers and loyal German immigrants represented a majority, there was a decided reluctance to break with the king. In relatively remote Adams County the Scotch- Irish were driven more by a passion for self rule and resentment towards the Crown’s arrogant tax levies. Here there was strong sentiment for breaking the tie with Britain. When the war came, Adams County men volunteered to fight. Town settlement and the like were naturally put on hold until the issue was resolved.

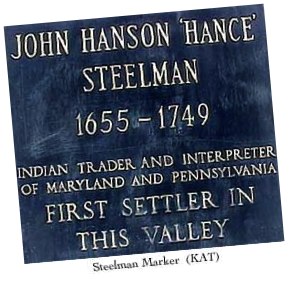

The creation of towns meant that the frontier of sparsely located homestead settlers was giving away to the more advanced state of settlements. By the eve of the American revolution the frontier line had passed well to the west of the Marsh Creek settlement. Sides over the issue of loyalty to the crown or to the patriot's call to break with Great Britain was sharply divided in Pennsylvania. In the older, established eastern counties and the City of Philadelphia, where passive Quakers and loyal German immigrants represented a majority, there was a decided reluctance to break with the king. In relatively remote Adams County the Scotch- Irish were driven more by a passion for self rule and resentment towards the Crown’s arrogant tax levies. Here there was strong sentiment for breaking the tie with Britain. When the war came, Adams County men volunteered to fight. Town settlement and the like were naturally put on hold until the issue was resolved. When the war ended in American independence so ended the Colonial Period. The process of development in the Adams County picked up where it left off with a renewed enthusiasm. In this spirit James Getty bought 168 acres and his father's house/tavern with an ambitious plan to lay out a brand new town smack in the center of the area which would soon become Adams County. He laid out a plan along a east-west and north-south axis with 210 sixty foot wide lots and offered each for $10 plus an annual ground rent of $1. The date for this town lot offer was January 10, 1786, the official birth date of Gettysburg. It would be 22 months later before the first three deeds were issued.

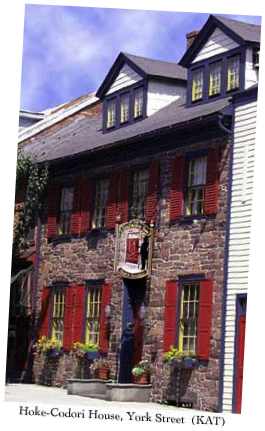

When the war ended in American independence so ended the Colonial Period. The process of development in the Adams County picked up where it left off with a renewed enthusiasm. In this spirit James Getty bought 168 acres and his father's house/tavern with an ambitious plan to lay out a brand new town smack in the center of the area which would soon become Adams County. He laid out a plan along a east-west and north-south axis with 210 sixty foot wide lots and offered each for $10 plus an annual ground rent of $1. The date for this town lot offer was January 10, 1786, the official birth date of Gettysburg. It would be 22 months later before the first three deeds were issued.  Two years later Michael Hoke finished his fine stone house in the first block of York Street [extant today as the Hoke-Codori house]. It would prove to be the first of many, many to follow over the next 200 plus years.

Two years later Michael Hoke finished his fine stone house in the first block of York Street [extant today as the Hoke-Codori house]. It would prove to be the first of many, many to follow over the next 200 plus years. THE COLONIAL PERIOD