EVOLVING TOURIST TOWN:

1880 to 1918

The veterans of the battle of Gettysburg adopted the battlefield as the proper site for the memorialization of their deeds here, and elsewhere throughout their service in the Union army. By 1880 the process of placing union regimental monuments was well underway. It would continue through the first decade of the 20th century. The frequent and elaborate dedication ceremonies were attended by surviving veterans, family and friends. This dramatic increase in veteran visitation was paralleled by a sudden interest in the battle among non-veteran citizens, primarily in the north, who also began arriving in significant numbers to tour the field. Their combined impact was a compelling increase in demand on the town for tourist services. The most essential were food, lodging and local transportation for visiting the field. The response of the town to accommodate this new demand marked the beginning of Gettysburg's evolution into a major tourist community.

All six of Gettysburg's hotels, which were carry over from the pre-civil war years, enlarged their properties. A seventh, The Central Hotel on Baltimore Street, was in full operation by 1880. New restaurants opened near the hotels and the train station.

The rising need for guided transportation over the battlefield stimulated the birth of a unique Gettysburg "industry" which still prospers today; the battlefield guide.  When the need presented itself a number of locals self designated themselves as guide-historians. They escorted visitors over the field delivering a personal interpretation of the significant battle events, incorporating a mix of some accurate history and some fascinating fictional anecdotes. Some of these guides, such as William Holtzworth a union army veteran, built excellent reputations and developed a loyal following among repeat visitors. When special dignitaries, such as President Rutherford B. Hayes, came to town more often than not they were escorted over the field by William Holtzworth. It was not until 1916 that the operation of local guides on the field was brought under some standard guidelines for pay, historical accuracy of presentation content and professionalism. This was brought about by the creation of a Licensed Battlefield Guide Association created, administered and monitored by the U.S. War Department.

When the need presented itself a number of locals self designated themselves as guide-historians. They escorted visitors over the field delivering a personal interpretation of the significant battle events, incorporating a mix of some accurate history and some fascinating fictional anecdotes. Some of these guides, such as William Holtzworth a union army veteran, built excellent reputations and developed a loyal following among repeat visitors. When special dignitaries, such as President Rutherford B. Hayes, came to town more often than not they were escorted over the field by William Holtzworth. It was not until 1916 that the operation of local guides on the field was brought under some standard guidelines for pay, historical accuracy of presentation content and professionalism. This was brought about by the creation of a Licensed Battlefield Guide Association created, administered and monitored by the U.S. War Department.

When the need presented itself a number of locals self designated themselves as guide-historians. They escorted visitors over the field delivering a personal interpretation of the significant battle events, incorporating a mix of some accurate history and some fascinating fictional anecdotes. Some of these guides, such as William Holtzworth a union army veteran, built excellent reputations and developed a loyal following among repeat visitors. When special dignitaries, such as President Rutherford B. Hayes, came to town more often than not they were escorted over the field by William Holtzworth. It was not until 1916 that the operation of local guides on the field was brought under some standard guidelines for pay, historical accuracy of presentation content and professionalism. This was brought about by the creation of a Licensed Battlefield Guide Association created, administered and monitored by the U.S. War Department.

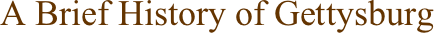

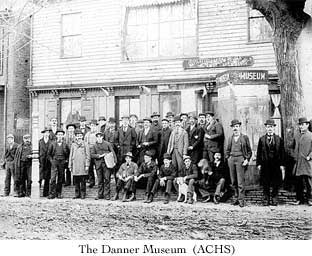

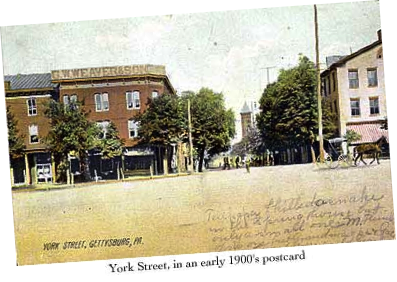

When the need presented itself a number of locals self designated themselves as guide-historians. They escorted visitors over the field delivering a personal interpretation of the significant battle events, incorporating a mix of some accurate history and some fascinating fictional anecdotes. Some of these guides, such as William Holtzworth a union army veteran, built excellent reputations and developed a loyal following among repeat visitors. When special dignitaries, such as President Rutherford B. Hayes, came to town more often than not they were escorted over the field by William Holtzworth. It was not until 1916 that the operation of local guides on the field was brought under some standard guidelines for pay, historical accuracy of presentation content and professionalism. This was brought about by the creation of a Licensed Battlefield Guide Association created, administered and monitored by the U.S. War Department. The growth of tourism spawned new business opportunities ancillary to the actual tour of the field. A few entrepreneurs such as Edward Woodward and Joel A. Danner opened shops for selling bullets and other battlefield artifacts crafted into pleasing displays, such as desk sets, to the tourists as souvenirs of the Battle of Gettysburg. These were particularly popular with the veterans. A few years later the souvenir line was expanded to include crude walking sticks or canes, allegedly cut from saplings growing on the most famous battle sites. Soon after the turn of the century postcards reflecting every notable scene on the battlefield were being hawked along with the older souvenirs. Many of these items were for sale in restaurants and hotel lobbies catering to the visitors to the battlefield.

The growth of tourism spawned new business opportunities ancillary to the actual tour of the field. A few entrepreneurs such as Edward Woodward and Joel A. Danner opened shops for selling bullets and other battlefield artifacts crafted into pleasing displays, such as desk sets, to the tourists as souvenirs of the Battle of Gettysburg. These were particularly popular with the veterans. A few years later the souvenir line was expanded to include crude walking sticks or canes, allegedly cut from saplings growing on the most famous battle sites. Soon after the turn of the century postcards reflecting every notable scene on the battlefield were being hawked along with the older souvenirs. Many of these items were for sale in restaurants and hotel lobbies catering to the visitors to the battlefield.

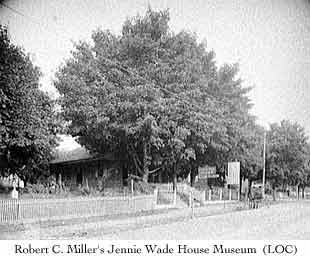

In 1900 a new type of tourist business was opened. Local entrepreneur, Robert C. Miller, offered the first combined free museum and souvenir shop in an historic location. Miller’s attraction was located in the house in which Jennie Wade was killed. It’s popularity with tourists soon made the ‘Jennie Wade House’ the most notable historic battle-related site not in the Park itself. Other historic museum- souvenir sites such as the Lincoln bedroom in the Wills House and General Lee's Headquarters would come much later. They would never quite rival the visiting public's fascination with the site of Gettysburg's lone civilian fatality and tragic heroine. Ironically the home of Gettysburg's first civilian hero, John Burns, was never commercially exploited and was quietly razed in the mid 1890s.

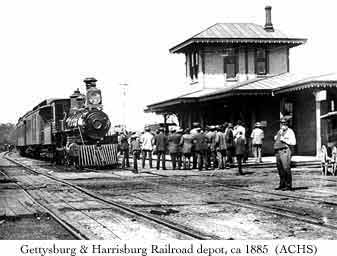

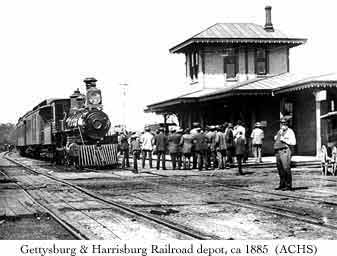

The escalation in tourist visitation had other dramatic impacts which effected the local economy and the quality of town life. During the two decades following the battle, visitors to the battlefield from distant locations arrived via the Gettysburg- Hanover Railroad line. The route was adequate but roundabout, requiring a transfer at Hanover Junction with the Northern Central line which carried the cars to Harrisburg or Baltimore. 1884 brought a second line into Gettysburg which offered a faster, more direct route to Harrisburg. From there convenient transfers to almost all major cities were available. The second line, the Gettysburg- Harrisburg Railroad, was completed in 1884. It's one story, frame and weatherboard passenger station, located on the NW corner of North Washington and Railroad Streets, still stands today as part of the Gettysburg College campus.  A ceremony of driving the last spike completing the track was held along the eastern face of Oak Ridge. Besides the usual speeches there were blasts from the local Democratic Party's celebration cannon, Penelope Ann, and a newer Republican Party rival cannon, The General Meade. The occasion was a bipartisan celebration.

A ceremony of driving the last spike completing the track was held along the eastern face of Oak Ridge. Besides the usual speeches there were blasts from the local Democratic Party's celebration cannon, Penelope Ann, and a newer Republican Party rival cannon, The General Meade. The occasion was a bipartisan celebration.

A ceremony of driving the last spike completing the track was held along the eastern face of Oak Ridge. Besides the usual speeches there were blasts from the local Democratic Party's celebration cannon, Penelope Ann, and a newer Republican Party rival cannon, The General Meade. The occasion was a bipartisan celebration.

A ceremony of driving the last spike completing the track was held along the eastern face of Oak Ridge. Besides the usual speeches there were blasts from the local Democratic Party's celebration cannon, Penelope Ann, and a newer Republican Party rival cannon, The General Meade. The occasion was a bipartisan celebration. A few years later a spur from this line was laid across the battlefields to the south of town to terminate at Sedgewick Post Office just a few yards west of the intersection of the Wheatfield and Taneytown Roads. John Rosensteel, a resident of Sedgewick, built a dance pavilion attached to his home and relic museum. Excursions to this spot on Saturday evenings during the summer became a major social outing for Gettysburg residents during the late 1880s and into the 1890s.

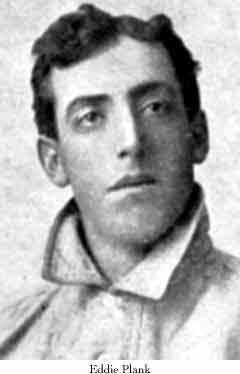

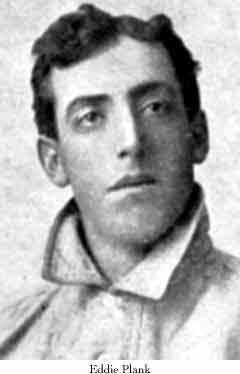

Saturday night dancing was not the only leisure time activity Gettysburg citizens utilized to escape the humdrum of life’s daily routine. Competitive sports became very popular for fan and participant alike. The first efforts were games in football and baseball against the college team. While exciting they were not very competitive. In 1898 the “townies” were trounced 116 to 0 in their first and last gridiron contest against the collegians.  Baseball quickly emerged as the community’s sport of choice. The field of competition spread to other towns in Adams and nearby York County. Young boys learned the skills on vacant lots until they were old enough to play for the town team. In 1901 a local phenomenon named Eddie Plank pitched his way onto the roster of the Philadelphia Athletics. Plank stayed in the majors 17 years earning membership into the Hall of Fame and the nickname of “Gettysburg Eddie”. Interest in Plank’s career fueled local fan enthusiasm for the game at every level, which earned the town a minor league franchise in the Blue Ridge League in the summer of 1915. The declaration of the U.S. entry into WWI suspended the league at the end of the 1917 season.

Baseball quickly emerged as the community’s sport of choice. The field of competition spread to other towns in Adams and nearby York County. Young boys learned the skills on vacant lots until they were old enough to play for the town team. In 1901 a local phenomenon named Eddie Plank pitched his way onto the roster of the Philadelphia Athletics. Plank stayed in the majors 17 years earning membership into the Hall of Fame and the nickname of “Gettysburg Eddie”. Interest in Plank’s career fueled local fan enthusiasm for the game at every level, which earned the town a minor league franchise in the Blue Ridge League in the summer of 1915. The declaration of the U.S. entry into WWI suspended the league at the end of the 1917 season.

Baseball quickly emerged as the community’s sport of choice. The field of competition spread to other towns in Adams and nearby York County. Young boys learned the skills on vacant lots until they were old enough to play for the town team. In 1901 a local phenomenon named Eddie Plank pitched his way onto the roster of the Philadelphia Athletics. Plank stayed in the majors 17 years earning membership into the Hall of Fame and the nickname of “Gettysburg Eddie”. Interest in Plank’s career fueled local fan enthusiasm for the game at every level, which earned the town a minor league franchise in the Blue Ridge League in the summer of 1915. The declaration of the U.S. entry into WWI suspended the league at the end of the 1917 season.

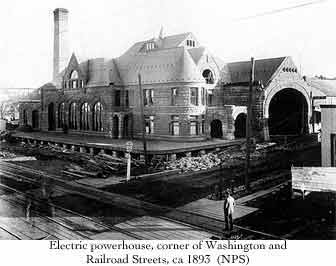

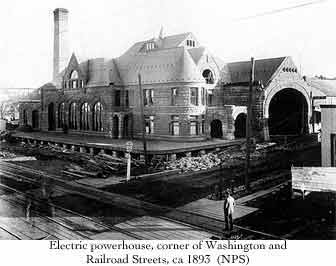

Baseball quickly emerged as the community’s sport of choice. The field of competition spread to other towns in Adams and nearby York County. Young boys learned the skills on vacant lots until they were old enough to play for the town team. In 1901 a local phenomenon named Eddie Plank pitched his way onto the roster of the Philadelphia Athletics. Plank stayed in the majors 17 years earning membership into the Hall of Fame and the nickname of “Gettysburg Eddie”. Interest in Plank’s career fueled local fan enthusiasm for the game at every level, which earned the town a minor league franchise in the Blue Ridge League in the summer of 1915. The declaration of the U.S. entry into WWI suspended the league at the end of the 1917 season. Another major addition to the local infrastructure brought about by the growing battlefield tourism was transportation related. In 1891 the Gettysburg Electric Railway was incorporated. In 1894 the line was completed providing a circuit originating at the Carlisle Street railroad station, proceeding down Baltimore Street, and looping around the south end of the battlefield, including a stop at John Rosensteel's pavilion, before returning to Gettysburg along the Emmitsburg Road and up S. Washington Street. The return leg terminated at the new electrical power plant built on the S.E. corner of N. Washington and Railroad Streets to provide power to drive the trolleys.  The line was used by tourists and local citizens alike. The latter used it mainly for getting around town or out to Rosensteel's on a Saturday night. A side benefit was having the first electric generating source in town which enabled the town to replace expensive gas street lamps with inexpensive electricity. Electric illumination in private homes and buildings would not appear until two decades later.

The line was used by tourists and local citizens alike. The latter used it mainly for getting around town or out to Rosensteel's on a Saturday night. A side benefit was having the first electric generating source in town which enabled the town to replace expensive gas street lamps with inexpensive electricity. Electric illumination in private homes and buildings would not appear until two decades later.

The line was used by tourists and local citizens alike. The latter used it mainly for getting around town or out to Rosensteel's on a Saturday night. A side benefit was having the first electric generating source in town which enabled the town to replace expensive gas street lamps with inexpensive electricity. Electric illumination in private homes and buildings would not appear until two decades later.

The line was used by tourists and local citizens alike. The latter used it mainly for getting around town or out to Rosensteel's on a Saturday night. A side benefit was having the first electric generating source in town which enabled the town to replace expensive gas street lamps with inexpensive electricity. Electric illumination in private homes and buildings would not appear until two decades later. While tourism continued to grow and forge changes in the economic face of Gettysburg, other aspects of the town's historic business structure were also going through changes. Factory based manufacturing finally made a significant inroad with the ending of the 19th century. Furniture was the leader in this conversion from the traditional craftsman/ cottage industry mode of manufacturing, replacing such time honored names as Garlach, Brown and Culp. In the early 1900s four separate furniture companies were operating in Gettysburg and employing approximately 600 employees. Two of these were bought out and formed the Reaser Furniture Company, which stayed in operation until 1960 under the name of the Gettysburg Furniture Co.

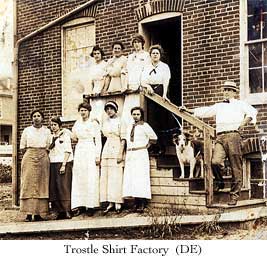

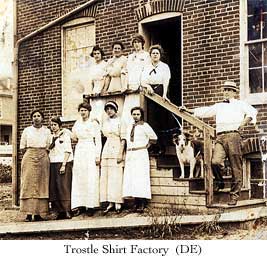

Other factories followed the lead set by furniture. Several sewing factories were founded to produce men’s and women's clothes, providing a substantial number of jobs for Gettysburg's female labor force.  New factories produced shoes, knives, cigars and boxes. In the 1920s a silk throwing factory would be built west of town near Buford Avenue. None of these enterprises lasted in town as long as the Gettysburg Furniture Co.

New factories produced shoes, knives, cigars and boxes. In the 1920s a silk throwing factory would be built west of town near Buford Avenue. None of these enterprises lasted in town as long as the Gettysburg Furniture Co.

New factories produced shoes, knives, cigars and boxes. In the 1920s a silk throwing factory would be built west of town near Buford Avenue. None of these enterprises lasted in town as long as the Gettysburg Furniture Co.

New factories produced shoes, knives, cigars and boxes. In the 1920s a silk throwing factory would be built west of town near Buford Avenue. None of these enterprises lasted in town as long as the Gettysburg Furniture Co. One factor for the successful emergence of the factory system in Gettysburg and in other areas of Adams County was the lack of labor unrest. Union organization was absent from the mix, and labor unrest and agitation was not a disruption to production as it was in almost every other manufacturing center in the country. Even so, not every manufacturing endeavor in Gettysburg succeeded during this “golden age” for the industry. Shortly after the Gilbert Foundry on N. Franklin Street finished casting the iron cannon carriages for mounting and displaying the Gettysburg National Military Park's collection of civil war artillery tubes, the sixty year old factory went out of business. It had been the first factory opened in Gettysburg, dating back to well before the civil war.

In the early 1880s the public educational system had made little change, but pressures to do so were emerging. The first and foremost was the pressure to expand the classes offered beyond the elementary level to include a secondary curriculum. This was initially accomplished in 1884 by expanding the number of subject courses taught in the elementary school. An initial class of ten students made up Gettysburg's first public secondary or high school class. They graduated from their three year curriculum in 1887. While the school term had been extended from 5 to 51/2 months it would be twenty years later before the high school curriculum would be expanded to four years.

The fact of racially segregated public schools did not change substantially. The African American elementary aged children continued to attend the "Franklin School,” three blocks distant from the white "Union School” building on E. High Street. There was one concession toward desegregation when the secondary school curriculum was initiated. African American children desiring to achieve public secondary education were accepted in the high school course taught at the "Union School.” The position of teaching at the “Franklin School” was not officially segregated. Lloyd Watts was the first black teacher, but this was the exception rather than the rule.  He was succeeded by other black teachers and white ones as well including Mrs. Salome Myers Stewart, former assistant principal at the “Union School” during 1863.

He was succeeded by other black teachers and white ones as well including Mrs. Salome Myers Stewart, former assistant principal at the “Union School” during 1863.

He was succeeded by other black teachers and white ones as well including Mrs. Salome Myers Stewart, former assistant principal at the “Union School” during 1863.

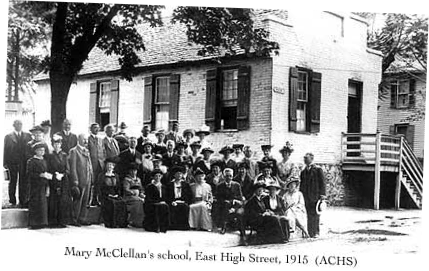

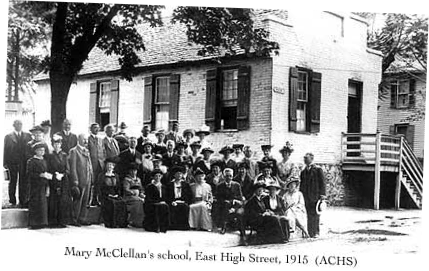

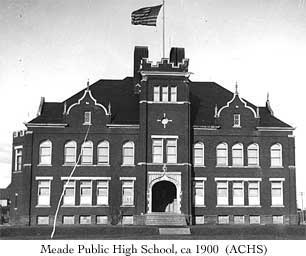

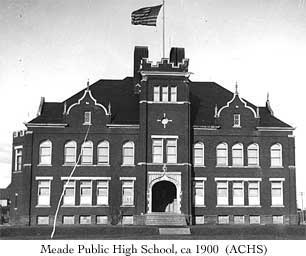

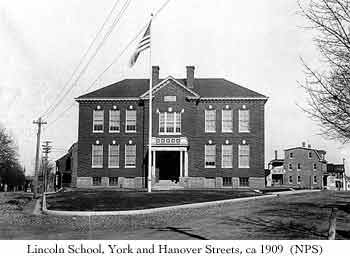

He was succeeded by other black teachers and white ones as well including Mrs. Salome Myers Stewart, former assistant principal at the “Union School” during 1863. The creation of a public high school curriculum, marked the beginning of the end for the many “private” schools which had been meeting this need in Gettysburg for almost eighty years. One of the last to go was Miss Mary McClellan’s “East High Street School” adjoining the county jail property. The growth in demand on the public “Union School” building, created by a combination of population growth and the high school program, caused the borough’s school directors to build an additional school building.  In 1897 the Meade Public High School, located at the junction of Springs and Buford Avenues, opened. The “Union School” remained in operation as the elementary school. Meade would serve as the high school until 1909. By then Meade School was overwhelmed by the demands of high school students. A third school was needed. The Lincoln High School was erected at the east end of town in the fork at Hanover and York Streets. It became the high school while Meade was devoted to the new “middle school” curriculum.

In 1897 the Meade Public High School, located at the junction of Springs and Buford Avenues, opened. The “Union School” remained in operation as the elementary school. Meade would serve as the high school until 1909. By then Meade School was overwhelmed by the demands of high school students. A third school was needed. The Lincoln High School was erected at the east end of town in the fork at Hanover and York Streets. It became the high school while Meade was devoted to the new “middle school” curriculum.

In 1897 the Meade Public High School, located at the junction of Springs and Buford Avenues, opened. The “Union School” remained in operation as the elementary school. Meade would serve as the high school until 1909. By then Meade School was overwhelmed by the demands of high school students. A third school was needed. The Lincoln High School was erected at the east end of town in the fork at Hanover and York Streets. It became the high school while Meade was devoted to the new “middle school” curriculum.

In 1897 the Meade Public High School, located at the junction of Springs and Buford Avenues, opened. The “Union School” remained in operation as the elementary school. Meade would serve as the high school until 1909. By then Meade School was overwhelmed by the demands of high school students. A third school was needed. The Lincoln High School was erected at the east end of town in the fork at Hanover and York Streets. It became the high school while Meade was devoted to the new “middle school” curriculum. Growth in educational facilities was not restricted to the town’s public school system. The college, too, was expanding to meet the demands of a growing student body and an ever widening course curriculum.  Between 1868 and 1905 six new buildings had been added to the campus. It admitted its first women freshmen in 1888. As the student body grew and turned to the town’s attractions for diversion from the study routine, student -“townie” confrontations became a frequent occurrence. The unofficial territorial dividing line was Rail Road Street, between Carlisle and N. Washington Streets. Excursions over the line by either side often resulted in bloody noses for the trespasser.

Between 1868 and 1905 six new buildings had been added to the campus. It admitted its first women freshmen in 1888. As the student body grew and turned to the town’s attractions for diversion from the study routine, student -“townie” confrontations became a frequent occurrence. The unofficial territorial dividing line was Rail Road Street, between Carlisle and N. Washington Streets. Excursions over the line by either side often resulted in bloody noses for the trespasser.

Between 1868 and 1905 six new buildings had been added to the campus. It admitted its first women freshmen in 1888. As the student body grew and turned to the town’s attractions for diversion from the study routine, student -“townie” confrontations became a frequent occurrence. The unofficial territorial dividing line was Rail Road Street, between Carlisle and N. Washington Streets. Excursions over the line by either side often resulted in bloody noses for the trespasser.

Between 1868 and 1905 six new buildings had been added to the campus. It admitted its first women freshmen in 1888. As the student body grew and turned to the town’s attractions for diversion from the study routine, student -“townie” confrontations became a frequent occurrence. The unofficial territorial dividing line was Rail Road Street, between Carlisle and N. Washington Streets. Excursions over the line by either side often resulted in bloody noses for the trespasser. Up on “the Glorious Hill,” the Lutheran Seminary was undergoing similar, but more modest growing pains. The “old dorm” building was augmented by the addition of Valentine Hall in 1894. The seminary students did not have a contentious relationship with the “townies” as did the college undergraduates, hence there was no “deadline” to be braved when going into town.

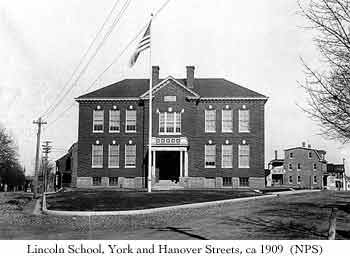

Like the learning institutions, churches also changed. The Methodists left their 1822 building and built a larger church across the street. Their old structure became the G.A.R. hall. The congregation of St. Paul’s A.M.E. Zion Church moved from their original building on Long Lane to a new site at the intersection of South Washington and Breckenridge Streets in 1886. In 1917 they significantly renovated their sanctuary into the structure that still serves today.

The town gained two protestant churches and lost another one by the end of the century. The Episcopal Chapel, with seating capacity for only one hundred twenty five, was erected at Carlisle and Stevens Streets in 1876 to serve a modest congregation. The membership grew rapidly and a new battle memorial church, The Prince of Peace Memorial Church , was constructed at the corner of Baltimore and W. High Streets. Begun in 1888, the 25th anniversary of the battle, the church doors were finally opened in 1900.

While the new Episcopal Church was being constructed the town’s oldest congregation was dying out. The United Presbyterian Church building was erected in 1805. Seventy years later it was considered obsolete in regards to the congregation’s needs and members began to shift to Gettysburg’s newer Presbyterian congregation. The old building, having nobly served humanity as a hospital in July 1863, was abandoned and sold in 1891. It was soon demolished and replaced with another church building by the United Brethren congregation, known locally as the “German Methodists.”

Change too touched the town’s long standing weekly newspaper service. Shortly after the end of the civil war the old Star and Banner merged with Robert G. Harper’s Sentinel, and continued to champion the Republican Party under the new name of The Star and Sentinel. Their equally partisan democratic opponent, Henry Stahle’s Compiler, remained unchanged. By the mid 1890s both of these old antagonist-editors had died, but their successors carried on the never ending political debate. In 1905 Gettysburg finally gained a daily newspaper, The Gettysburg Times. The publisher proudly claimed that his paper was bipartisan and would be printed only to deliver the news. Subsequent publishers have maintained the stance of political neutrality.

The face of Gettysburg underwent a major change in the last decade and a half of the 19th century. The early architectural appearance was significantly modified by face lifting more often than by demolition. Many of the old two story buildings in the center of town were raised to three and given a updated front facade. Some replacement was intermixed with renovation. This is readily visible today with the mix of old and new seen in Lincoln Square and the first block of Chambersburg Street. By the turn of the century the face of downtown Gettysburg architecture reflected an 1885-95 structural renaissance, replacing the pre-civil war character that had prevailed for most of the town’s existence. Over a century later that face is still largely intact.

The outlying areas of the borough kept pace with the downtown building boom. The north end of town continued to develop with the expansion of Martin Winter’s Broadway Avenue development. This was paralleled by new construction on Carlisle Street east to North Stratton. Still further east, new construction on York Street, beyond 3rd Street in the area long ago called `Green Fields’, pushed towards Rock Creek. In the south end of town along Baltimore Street new residential houses filled out the open lots which predominated in 1863 and the two tanning yards, Winebrenner’s and Rupp’s disappeared.

Other changes outside the borough limits, but with significant and lasting impact on the town, began as the 19th century drew to a close. In 1896 the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) transferred it’s battlefield holdings to the U.S. Government. The year before the U.S. Congress passed a bill creating a National Military Park out of the Gettysburg battlefield. The War Department was given responsibility for the care and development of the park which by congressional order was to include the grounds occupied by the Confederate troops. A Gettysburg Battlefield Commission comprised of three Civil War veterans was formed to manage the park’s development. The Commission and staff leased quarters on the 2nd floor of the Winter Building at present day 17-19 Chambersburg Street. For the first time a Federal presence, other than the U.S. Post Office, was permanently ensconced in the Borough of Gettysburg. The Battlefield Commission had a widely different set of objectives for the development and preservation of the field than that of the previous caretaker, the GBMA, which had always been considered by the townspeople as a locally oriented organization. The biggest differences were the Commission’s charge to acquire much additional land including that which made up the Confederate battle lines, and a decision process that focused on national perspectives rather than just local considerations. It was natural that tensions between the Commissioners and the local inhabitants would arise from time to time because of these new and different objectives. These early differences with Federal mandated objectives would grow and become the geneses of the very prominent, long standing, love- hate relationship existing between park management and the local population.

The creation of the Gettysburg National Military Park (GNMP) was an instant boon to the local town economy. While the veterans process of memorializing the field with regimental monuments was winding down, the expansion of the park and the placement of interpretive markers by the War Department was increasing public interest and visitation. Being a national military park made the grounds available to military organizations for training purposes. The Pennsylvania National Guard was the first to use that opportunity and began holding annual two week summer encampments on the field right after the turn of the century. Once again Gettysburg felt the surge of an economic windfall hosting the Guard and their visiting families and friends.

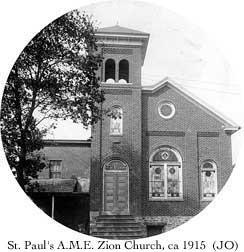

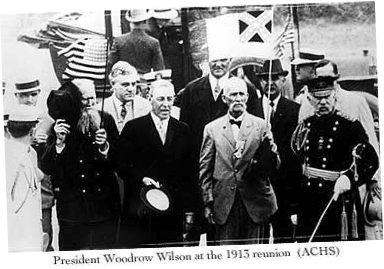

The biggest Park related economic event was yet to come. It would be the Grand Reunion of Union and Confederate veterans on the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1913. It would generate an invasion of the town which closely rivaled the numbers of persons who came to Gettysburg with the two opposing armies in July 1863. The up coming fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg was seen by most veterans as a significant milestone in the half century long process of healing the wounds of bitterness which had prevailed between the old adversaries since the war ended. It was seen as the event that could physically and symbolically bring the old warriors together for a final forgiving and rebinding of the still emotionally separated factions of the country. Proposed formally by the Governor of Pennsylvania in 1908, the idea excited the imagination of veterans, politicians and citizens across the nation. All but African American leaders who saw it as just a white man’s reconciliation, which completely ignored the correction of existing civil rights inequities, which was a core objective for fighting the war.

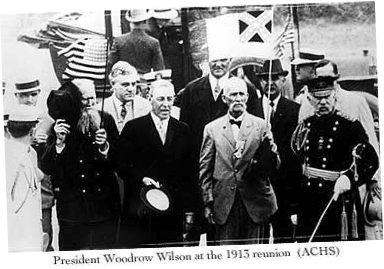

Not withstanding the racial politics of the affair, a four day joint reunion was set for July 1st - 4th, 1913. Unlike fifty years earlier the town did not have to deal with the logistical impact of their “guests.” The state governments all contributed funds along with the federal government. The U.S. Army set up and administered the veterans tent camp which extended from just north of the Cordori farm house on the Emmitsburg Road north east to South Washington Street, and then north into town almost to Breckenridge Street, and then west to Seminary ridge at the McMillan farm. 55,400 veterans and over 100,000 visitors attended the encampment. The veterans arrived by rail on both the Western Maryland and the Gettysburg, Harrisburg and Reading lines. Many visitors for the first time came in significant numbers by automobiles, portending the future revolution of visitor means of transportation to Gettysburg. Dignitaries, including President Woodrow Wilson, attended despite the boiling July temperatures. Surviving photographs, newspaper accounts and personal memoirs attest to the success of the affair. Two London correspondents, writing on July 4th, best captured the spirit and impact of the Grand Reunion. THE LONDON TELEGRAPH: “European civilization...has not yet furnished a spectacle comparable to that witnessed...on the historic battlefield of Gettysburg.” THE LONDON TIMES: “..the mingling of the Blue and Gray has been heralded as eradicating forever the scars of the civil war in a way no amount of preaching or political maneuvering could have done.”

Despite the overwhelming demonstration of goodwill between the former enemies there was one incident of combat between old warriors. During an early afternoon lunch in the Hotel Gettysburg dining room an isolated altercation broke out and one old veteran pulled out a knife and stabbed another. Fortunately the wound was superficial.

When the crowds and veterans had all departed by July 6th, the health of the Gettysburg tourist industry was robust. The interest in the battlefield generated by the prolific daily coverage of newspaper reporters from all over the country provided a national surge in visitation to Gettysburg which was interrupted only by America’s entry into WWI.

The U.S. Congress officially declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. Gettysburg, like all other towns across the nation, was full of patriotic support. Unlike the rest of the nation’s towns they enjoyed the unique position of being able to offer to host the army’s training needs. Shortly after the declaration of war a group of prominent citizens sent a telegram to President Wilson and the Secretary of War recommending, “a training camp on the great battlefield at Gettysburg.” The recommendation was more of an offer, touting the many support capabilities of the area. Was the offer an act of patriotism or a shrewd business maneuver? Several thousand semi permanent soldiers living on the outskirts of town would serve as nice economic buffer to a war diminished tourist trade. The offer was interesting from another aspect. The Park was not the town’s to give. It reflects the subconscious notion of local proprietorship that has persisted since the inception of the GBMA. Regardless of the motive behind the offer, news soon came that an infantry training camp would be established on the fields of the park. It is not known if the town’s gesture had any influence in the War Department’s decision.

On June 1st the vanguard of what would be 15,000 soldiers arrived in town and began setting up camp along the Emmitsburg Road. Soon tents covered the fields on both sides of the road from the Codori farm buildings southward almost to the Sherfy house. The Headquarters camp was established in the field north of Codori’s and east of the road, the very field over which Pickett’s and Pettigrew’s men made their final and unsuccessful dash to the union center on July 3, 1863. In October the army corps of engineers began to “harden” the camp with heated wooden barracks and buried water lines in preparation for the coming winter. Some of the troops would leave before the winter set in, but the rest stayed until the early spring.

The town opened their front door of hospitality to the trainees and their officers. Reading rooms for the enlisted men were set up in the First National Bank and the Sunday School room of the Christ Lutheran Church. In a building at 37 W. Middle Street an officer’s club was established. At St. James Lutheran Church a canteen was provided for the enlisted men. Since this was before the days of army post PXs. Gettysburg’s shops and stores benefitted from the soldier’s patronage.

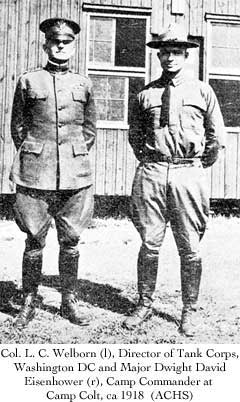

After the departure of the infantry in the spring there was a short interval of inactivity in the army camp, which had never been given an official name. By the end of March 1918 the vanguard of a tank battalion arrived to renew training activities on the battlefield. The facilities were in place. The full cadre would swell to 8,000. The camp would be named Camp Colt. The commander would be a captain who’s name, like Abraham Lincoln, would forever after be associated with Gettysburg, Dwight David Eisenhower. “Ike” brought his wife Mamie with him and the couple lived briefly in a house at 157 N. Washington Street before moving to their permanent Gettysburg lodging at 263 Springs Avenue. Their stay at Gettysburg was only for six months, but left a lasting impression on the couple. After retiring from the Army as the WWII hero and a four star General, the Eisenhower’s would return to the area to establish their permanent home. They purchased a farm on the southern edge of the battlefield in 1951. Their residency was interrupted by Ike’s serving two terms as President. In 1960 they were finally free to settle into retirement at Gettysburg.

The town welcomed the tankers as they had the foot soldiers just months before. Soldiers packed the street pavements when ever they could get free time. As before a canteen was set up. A “Soldiers Club” was established in a house where showers were available and the men could meet with visiting family. The officer’s club remained on W. Middle Street. As anticipated, the merchants prospered. The only unpleasantness occurred after now Lt. Col. Eisenhower became concerned about the frequency of troops returning to camp in a state of inebriation. Displaying the style of decisive command he would exercise as the Allied Supreme Commander in WWII, Ike used his wartime authority for martial law and closed all bars in Gettysburg and surrounding townships to soldiers and civilians alike. This brought forth some vocal anger on the part of some civilians and all tavern owners.

The town welcomed the tankers as they had the foot soldiers just months before. Soldiers packed the street pavements when ever they could get free time. As before a canteen was set up. A “Soldiers Club” was established in a house where showers were available and the men could meet with visiting family. The officer’s club remained on W. Middle Street. As anticipated, the merchants prospered. The only unpleasantness occurred after now Lt. Col. Eisenhower became concerned about the frequency of troops returning to camp in a state of inebriation. Displaying the style of decisive command he would exercise as the Allied Supreme Commander in WWII, Ike used his wartime authority for martial law and closed all bars in Gettysburg and surrounding townships to soldiers and civilians alike. This brought forth some vocal anger on the part of some civilians and all tavern owners. Before the situation could reach a climatic boiling point it was overshadowed by a much more devastating circumstance. Shortly after a detachment of new trainees arrived from Fort Devon in Massachusetts in early September, Camp Colt was struck by a deadly outbreak of influenza. By September 26th eight soldiers were dead. A week later 46 more had succumbed. The town was stretched to its limits, much as it had been in 1863, to deal with the emergency. The officers club in 37 W. Middle Street and the old GAR hall were converted to temporary morgues. Morticians struggled with the demand for coffins. Once again the St. Ignatius Roman Catholic Church was pressed into serving as a hospital for stricken soldiers. Once again the civilian women volunteered to provide food and personal care. Daily parades of flag draped coffins, accompanied by a military band playing a funeral dirge, led to the railroad depots to send soldiers “home.” The disease spread to a few in the civilian population. Before it subsided in early November the flu had claimed over 200 soldiers and civilians.

As the flu crisis abated the war in Europe ended with the surrender of Germany to the Allied forces. Immediately the troops began shipping out by rail to Fort Dix New Jersey for discharge processing. By the end of November Camp Colt was deserted, the Eisenhower’s were gone and the town’s bars were back in business. Gettysburg, like every other town and city, turned their attention to returning to the “normalcy” of peace time life.

EVOLVING TOURIST TOWN